CHAPTER FIFTEEN

MUNICH - FIRST IMPRESSIONS

The very first time I saw Munich from the air was on the day I was leaving, in 1955. If we don’t count the ride on the Ferris Wheel during Oktoberfest. My first introduction to the city was from ground level. Seven years after the war the wounds were still visible in places as we drove through the streets. Remains of houses, bombed during the war dotted the landscape. In fact, when the Olympic Park was built for the 1972 Olympic Games, the hills of the Park are made of the rubble of World War II.

I, of course, have not seen the Park. Nor had I acquaintance with the Underground Transit System. Buses and streetcars were the transportation during the years I lived there.

Let me orient you as to where we are. Munich lies in southern Bavaria, on the River Isar. On a clear day, the Alps are visible. That is unless the Foehn, the warm wind blowing off the mountains, which causes a condition similar to the California smog, inverting the layers of atmosphere. It also brings on a condition very similar to migraine headaches.

There are also many lakes nearby, forests, castles. A beautiful region to visit.

On the map below, you can trace our steps from Prague, through Plze

Á, into Germany. Weidhause is not on the map, but the city of Weiden, where we "served" our sentence, is. From there we went to Nürenburg, where the ‘Valka Lager’ was located. And on to München.I should mention that the German alphabet has a number of "umlaut" marks, two little dots over the vowels, which changes the sound of that vowel. In English we have no equivalent sounds, and typing on an English typewriter, which does not have the "umlaut", adding the letter ‘e’, is acceptable. Thus, Munich, the capital of Bavaria or Bayern, written München in German, could also be spelled out Muenchen, and read and pronounced the same way.

Now, to the map:

You can locate München in the lower center of the map.

The towns of Regensburg, north of München, Augsburg, west-by-northwest, and Tegernsee, just south will also appear in my narration.

The three years I had spent in Munich were the most carefree, happy years of my life. They were also the most difficult. I had learned great many lessons there, in and out of school. I had gained, after the first few months, many good friends, and one close friend, Dieter Meenen.

Most of the events during those years are closely tied in with Dieter, and a place called Prinz Regenten Stadium, a swimming pool by Summer, an ice skating ring by Winter.

And then there was Inge, Carla, Helga, Suzy, Gerda, Margot, Renate ....

This is what the Stadium looked like:

The concrete area in the rear of the photograph was the open air ice skating ring. Between it, the pool, the Kinos - the movie houses, the roller skating area in the Englischer Garten, the school, - Luitpold Oberrealschule, and the Radio Free Europe studios my life has moved, depending on the seasons.

But, I am getting ahead of myself.

When we first arrived in Munich, Father was a valued employee of the Radio Free Europe Czech Desk. And, as such, he had a brand new apartment on Franz-Joseph Strasse, he had a car, the Beetle we arrived in, and, he had a PX card. He was also paid in script, not in marks. Script were dollar-like currency issued in occupied Germany to the soldiers stationed there and all those employed by the American system. They were as good as gold anywhere, and the exchange rate to the German Marks was very high.

A person making, say four hundred script dollars a month, would be, in comparison to the German civilians, considered a very rich person. So, we were rich.

My recollections of the first impressions of the city are somewhat vague. Bits and pieces of that first year come and go.

I remember upon arrival I found a refrigerator full of food. I ate. Father was very angry, as I have eaten something he was keeping aside for himself.

I remember Frau Weber, Suzy’s mother, who came in twice a week to clean the apartment. As both Father and Mother were working full time, I was often at home alone with her. She was a tall, dark-haired woman of about thirty-three. Very beautiful and very lovely personality. She and I would talk; that is, she would talk and I would grunt. As I have mentioned, my knowledge of German was pretty much zero.

But she had a lot of patience, and little by little, I began to understand more and more of what she was saying. Her story was probably a representative one of many women not only of Munich, but of Germany as a whole.

She was from northern part of Germany, which was a blessing in disguise, as she spoke what is referred to as "Hoch-Deutsch", that is a dialect which is most correct in its grammar and pronounciation. Something akin to the "Queen’s English", as opposed, say, to an Alabama accent. The Bavarians have a heavy accent, often ‘swallowing’ a portion of the word, and have a whole series of words which do not appear in the dictionary.

Let me give you an example. In asking a question, the Germans often end with, "nichtwahr?", meaning, isn’t that so? or isn’t that right?. The Bavarians have changed that over the years to something that sounds like "nettwah?". In addition, they have a word that sounds like "gell?", with the hard "g" sound, which means about the same thing.

To someone trying to learn the language, this can be highly confusing. Frau Weber’s ability to speak a ‘correct’ version of the language helped me. Her daughter, Suzy, who was my age, and who came with her sometimes, also could speak that version, though she often relapsed into the dialect. But that had helped as well. I did not get too friendly with Suzy at this time.

In a downstairs apartment lived another Czech couple with two daughters. The older one had married and moved out, so I did not know her very well. The younger girl, who was six or seven, often came upstairs, or I went downstairs, when the Halik family had to work and did not want to leave Michelle - I called her "Myšinka", the sound being the same, I made a play on words. Her nickname meant Little Mouse. She was quiet like one, not at all hard to baby-sit. She had gotten used to me, and often I would need to go down and put her to bed, as she refused to go to bed for her mother.

Her mother was a beautiful woman. She used to be a ballet dancer, until the veins in her legs caved in, now retired, she worked as a secretary. Although Mr Halik was tall also, I am sure the willow body Michelle inherited from her mother.

It was funny to watch the adults struggle with the language, which came so easily to the two of us. The shopping for food was negotiated by Michelle and me. At first, the parents, that is my mother and her mother, would go with us. Michelle and I did all the talking.

The stores in Munich were not like the supermarkets we find here, in the States. Although the size was probably equivalent, there was not the self-service cart filling and unloading as there is here. All departments were manned - well, actually "womenned" - by clerks, who took your orders, showed you the meats or the bread or the fruit, cut it to order, and wrapped it. The food was later delivered to the homes.

As the store was just half a block down the street, we shopped almost daily, and only for what we planned to use on that day. To me that meant that I got to see the delivery person every day. I liked that, and made sure I was home when she arrived. Yup, she! She was a girl about a year older than I, with curly brown hair, eyelashes that movie queens would kill for, and a lovely figure. She appeared to suffer still from the ravages of the war, as her clothing, though clean and well kept, was threadbare. She always had a sweet smile for me and a friendly "Grüss Gott".

That was a common greeting, like our Hello or Good Day. Literally it means "Be greeted by the Lord", or "God greets you". The Bavarians ran that together, with the addition of the pronoun you, "Dich", so it sounded something like "Grüsstigott". I often planned to speak to her, rehearsing what I might say. I was going to take her out to dinner and a movie, and some ‘smooching’, though I did not really know what that might be. Yet, I never got the courage to even ask her name.

Within a year we moved and I never saw her again.

Speaking of movies, that was my constant entertainment. There were no televisions, of course, the radio was fun for a while, reading was great, but it too, became monotonous. So, I went to the movies. Each movie had its own "Programme", program. It was a two page flyer, with pictures from the movie, list of the cast, and a brief description of the plot. I collected those. By the end of the three years, I had over five hundred of them.

Beside the entertainment, movies also served another purpose. They exposed me to the language, as all foreign movies were dubbed into German. The words, combined with the action on the screen, helped me build up my vocabulary. By the end of the first year I spoke passable German, by the end of the second year, it was flawless. When I left Munich, only an expert would have been able to tell German was not my native tongue.

German grammar is also (like Czech) difficult. I was thankful for the school I enrolled in, as I learned the composition, grammar and syntax, to add to my vocabulary.

There was a severe shortage of men in Germany. The thousands that were killed during Hitler’s drive for world domination, left huge gaps. Also, many were still held prisoners in the labor camps of the Soviets, into the late fifties.

Available men were like honey to a hungry bee. Many German girls dated and married the GIs stationed there. I also had no problem in finding girls who would like to be friends. Part of that, I am sure, was the shortage of boys in general. Partly, because I was a foreign national, paid in script, with access to American cigarettes and - nylons!

Partly, I think, because I was ... well, good looking. intelligent, friendly and not stuck up, with a nice personality. Now, if only I had known what to do with them!

Like my barber, for example. Yes, you guessed it. The barbers were women. In my case a young sixteen-year old. I made sure she was always the one who cut my hair. As I always left her a very big tip, she was more than happy to guide me to her chair.

It was ... very pleasant sensation, to have her lean against me, as she cut here and snipped there. Needless to say, my haircuts were very, very frequent. Yet, as with my delivery person, I never even asked her name.

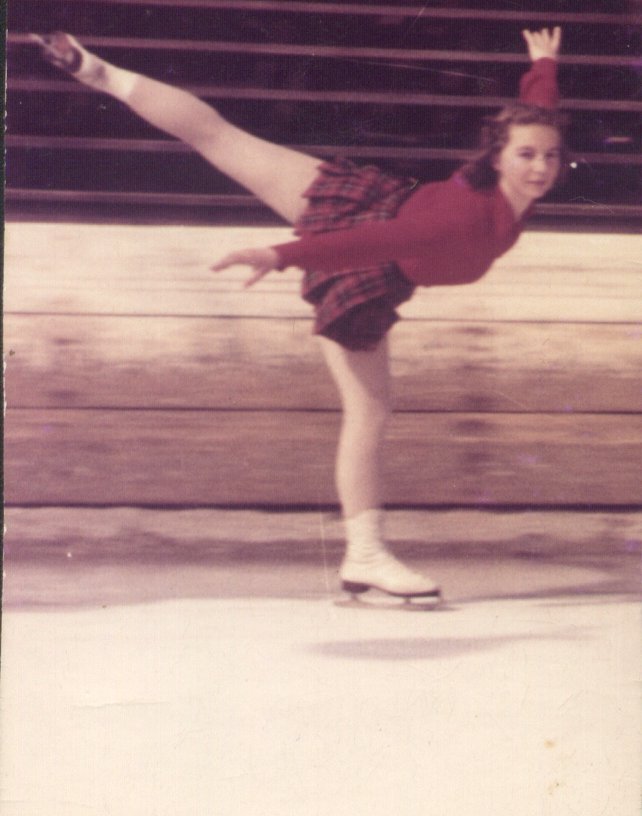

I was good looking. Many years ago. Here, let me show you.

The first photograph was taken by a street photographer. I was returning from some shopping. A new coat, it I remember correctly. That was shortly after our arrival, February 4, 1952. The second one was taken sometime in December of 1954 at the Printz Regenten Stadium.

I had skated since the age of four, on hockey skates. In the Winter of 1952 I discovered figure skating. Well, first, I discovered Carla.

I was so impressed with her grace and her ... talents, I went out and bought a pair of figure skates, enrolled in the same figure skating training as she, run by a man named Schnelldorfer, and also enrolled in the Summer gymnastics and roller skating programs.

I also met Dieter. Unfortunately, Carla was more interested in Dieter. I only got one little kiss from her and that was on the day I left Munich for America.

It did not, however, interfere with Dieter’s and mine friendship. Nor with my figure skating. I discovered I really enjoyed it, and became fairly proficient. To this day I follow all the national and international events - on television.

As time went on, I had found more friends on the ice and roller rink, I had no time to be sad over Carla’s choice.

Munich became my second home.

That is a very important statement. Please, remember it as you read the next chapters about my life in Munich.

The time between January and December of 1952 I spent pretty much alone. I did go swimming a lot at the Stadium, I worked for Radio Free Europe whenever roles for young voices were needed. I made enough money to sustain my movies, my day trips to museums, and the annual pass for the Stadium, as well as the streetcars.

In the Fall I started school. Oberrealschule is equivalent to a College in the US. In fact, when I enrolled at the Castleton State College in 1961, I was admitted as a sophomore, based on the credits I earned at the Oberrealschule.

The first few weeks were traumatic. The language barrier and the fact I was a Czech, from a country formerly occupied by Germany, and a national of a country that had forcibly moved hundreds of Czech nationals of German origin from the Sudeten after the war, in an effort to prevent another occurrence of internal uprising, as happened in 1938. The Sudeten Germans "demanded" to be annexed by Hitler’s Germany, which led to the downfall of the Republic. So, there were some bad feelings all around.

I, too, had some bigoted feelings toward my German colleagues, and the tension ran high. I almost quit after the first two weeks. Fortunately, the headmaster became aware of the situation and walked into the classroom one day to hold a peace tribunal. He spoke to the German boys as well as to me. He managed to help us to understand the futility of any war, the foolishness of all sides involved in the last war, the casualties, the high cost in human lives, and the need for a lasting peace. That peace would have to start with us.

It did.

My German has improved daily, and my ability to read Latin and my knowledge of history, combined with my love of literature, have all helped to raise my status in the eyes of my classmates. Although I never formed any close ties with any of them, we became at least tolerant toward each other.

Then came the Winter of 1952-1953.

As I already mentioned, I met Dieter, who was enrolled in the same training as I, and we had formed a close friendship. The current phrase is, we ‘bonded’.

Our families did as well. The Meenens became close friends with my mother and often we would visit. When I left, they all cried. Dieter, by the way, later married a beautiful Italian girl he met at the University. I do not know what happened to Carla.

During that Winter, my new life in Germany became less that of an immigrant and more of a person who belongs.

Those three years were the happiest and most painful of my life.