Recognition and degradation of faulty or aged proteins

[8]

Joost van Wijk Dr.

C. L. Woldringh

9878971

D. Defoelaan 200-a

1102 ZM Amsterdam

06-24684538

Contents

Abstract

Introduction

Chapter

I: Recognition of faulty proteins

Chapter

II: Degradation of ubiquitinated proteins

Conclusion

References

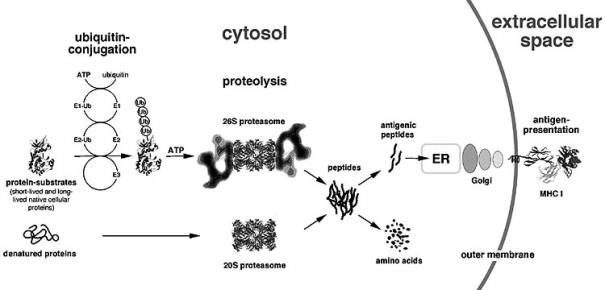

Abstract

DriPs (defective

ribosomal products) and aged proteins have to be degradated so that the cell

can work in a normal way.

This is done in the

proteasome, an enzyme that breaks the proteins in parts of eight to ten amino

acids. These amino acids can be reused.

Before the DriPs and aged

proteins are broken down in the proteasome, they first of course have to be

detected. This is a complicated process which is not yet completely clear.

It is clear that a couple

of enzyme complexes are needed: an E1 enzyme, an E2 enzyme and an E3 complex.

These complexes realise that an ubiquitin tag is attached to the DriP or aged

protein.

This tag can be detected

by the proteasomes and the ubiquitinated DriPs or aged proteins will be

destroyed by them.

Introduction

Many proteins are made in

a single cell daily, so many mistakes will be made by the transcription of the

genes and the translation of messenger RNA to proteins. Even when the proteins

are made correctly, they also have to be folded in the correct way. If this and

the prior goes wrong, the proteins have to be detected to be broken down; the

proteins do not function, so they have to be taken away and the amino acids

reused.

In this ‘mini-scription’

the detection of these faulty proteins and the degradation of them will be

described.

The main question thus is

how the proteins are marked for the degradation mechanism and in which way the

proteins are broken down by this mechanism.

Chapter I:

Recognition of faulty proteins

One of the most

interesting and important systems in our body is the system that recognises and

destroys faulty proteins in the cell.

Faulty proteins function

not fully or wrong because of transcription and/or translation errors. These

defective proteins are called defective ribosomal products (DriPs).

Approximately 30% of all

newly synthesised proteins are defective and thus called DriPs [6]. This great

amount of wrong proteins has to be diminished, because otherwise they could

interact with or disrupt vital processes.

The process of breaking

down the faulty proteins takes place in special enzymes: the proteasomes

[1],[2],[3],[5],[6],[7].

This has been examined by Schubert et al.; they wanted to

know whether these DRiPs were really degradated in the proteasome or by another

(still unknown) mechanism.

Therefore they added Lactacystin which stops the proteasome, or

zLLL which stops both proteasomes and other proteases.

They incubated cells with Lactocystin and zLLL, and this

resulted in an increased amount of protein in the cell. Apparently the

degradation mechanism did not work, so the degradation takes place in the

proteasomes and/or the proteases. But in which one, or in both?

To answer that question they incubated the cells with

Lactacystin and cells with zLLL. In both cases the protein amount in the cell

did increase the same.

So it is clear that the proteases do not break down the DriPs,

otherwise the cells where Lactacystin was added, should contain less proteins.

To prove that the DRiPs are degradated by proteasomes, another experiment was

required: zLL was added, which deactivates all proteases, but not proteasomes;

the result was that there was not an increase in protein amount in the cell.

The proteasome thus clearly is the enzyme-complex that breaks

down the DRiPs.

Before the DriPs are

processed in the proteasomes, they first have to be recognised by both the

proteasomes and the enzymes that tag the faulty proteins.

Proteasomes themselves do

not recognise the faulty proteins directly, they only detect proteins that have

a kind of tag, i.e. an ubiquitin tag [3],[5],[6].

It is interesting that

not only faulty proteins but also aged proteins obtain this tag. Both the

faulty and aged proteins bear specific destabilising N-terminal residues, which

in turn can be recognised by a system that will be described later.

These N-terminal residues only occur when the proteins either

are misfolded or aged. During aging these destabilising residues appear. The

half-life of a protein is determined by the speed of appearing of these

N-terminal residues [2].

The proteasomes only

destroy tagged proteins, whether they are old or just defective.

The main question now is:

how are the faulty or old proteins detected and tagged with ubiquitin?

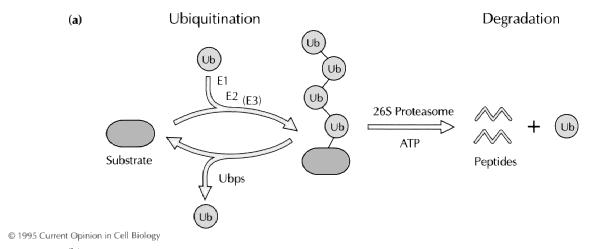

The process of tagging

the faulty proteins with ubiquitin is being revealed more and more; it has

become clear that there are a few enzymes that make sure that ubiquitin is

tagged onto the faulty or old proteins [7].

These enzymes have to be extremely specific: when they do not

only target faulty or old proteins but also normal proteins, disorder and chaos

in the cell occurs: many processes are disturbed [2].

Many different

ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes have been found and each possesses a different

kind of specificity for different classes of target proteins.

The system of recognising

and tagging the faulty or old proteins is now thought to function in the

following way.

Before the proteins will

go to the proteasome, they first have to be ubiquitinated; this process

involves three different enzymes: ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 which uses ATP to form high

energy bonds (thioesters) between itself and ubiquitin, the

uniquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 which takes the activated ubiquitin over from

the E1, and an ubiquitin ligasing enzyme E3. The E2 and E3 together make it

possible that the activated ubiquitin forms a peptide bond with the amino group

of a lysine in the targeted protein [5],[7].

Now the three different

enzymes have conjugated an ubiquitin chain to the lysine residues.

[2]

To get a better

impression of the exact functioning of the cascade, the cell-cycle control of

yeast cells has been studied [1].

In the yeast cells, the

proteins used in the cell cycle have to be destroyed very fast when they are

not needed anymore. Therefore the yeast cells also make use of a system for the

degradation of proteins by proteasomes; in this system the ubiquitination also

plays a role which can be used to better understand the mammalian protein

degradation system, because both systems are much alike.

A complex of Skp1-Cdc53

and Cul1-F-box (SCF complex) targets proteins for destruction, because it

functions as an E3 (a protein ligase); not only this complex is needed, also

Rbx1 and the E2 (ubiquitin conjugating enzyme) Cdc34 are necessary.

When the proteins ready

for degradation are detected and bound, the E2 Cdc34 conjugates an ubiquitin to

the protein. The protein is now detectable for degradation [1].

Only two of the three

important enzymes used in the detection of old and/or faulty proteins have been

mentioned: the E2 and the E3. The E1 though is also important: it presents the

recycled ubiquitin in an active state to the E2 complex.

So now can be concluded

that the detection of faulty or old proteins is done in the following way: an

E1 enzyme binds an ubiquitin and presents it in an active state to the E2

enzyme.

The E2 enzyme complexes

with the E3 complex, which binds an old or faulty protein. These old or faulty

proteins are detected by the destabilising N-terminus. The E2 attaches an

ubiquitin-chain to lysine residues of the protein.

Now the protein is ready

to be destroyed [1].

An example of how

important E2 (ubiquitin conjugating) enzymes are is when these enzymes are

absent: the cell will grow because of the continued acquiring of faulty

proteins and in some cases a stress response will occur. It is clear that the

E2 enzyme plays a major role and is necessary for the ubiquitination of faulty

or old proteins: when the E2 enzymes are absent, more and more proteins ready

for degradation are accumulated in the cell because they are not being tagged

with ubiquitin.

Thinking about this tagging machinery, it seems only to be a system that tags the faulty or old proteins, so that they can be broken down in the proteasomes; when the tagging system does not work, it will give rise to a stress response because less of the faulty or old proteins will be eliminated, and aggregation of the proteins occurs. Another effect of aggregation is when this aggregation takes place in the nucleus: diseases such as Huntington’s disease appear.

The forming of aggregates can be a result of over-expression of

misfolded proteins and the inhibition of the proteasome.

Most times, the proteins accumulate near the centrosome in a

pericentriolar region [5].

But what if the machinery

works too well? What if too many (also healthy) proteins will be tagged with

ubiquitin?

This will have dramatic

consequences: the

cell starts eating itself. It has been suggested that this might play an

important role in apoptosis [5].

In comparison with the

main function of ubiquitination, the abnormal ubiquitination is less important.

The most important is the detection and ubiquitination of faulty or old

proteins. After they have been ubiquitinated, they will be broken down in the

proteasomes.

Not only the process of

degradation of faulty proteins via ubiquitin tagging is regulated by these

ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, but also many other processes such as the

cell-cycle and programmed cell death are directed by them.

Chapter

II: Degradation of ubiquitinated proteins

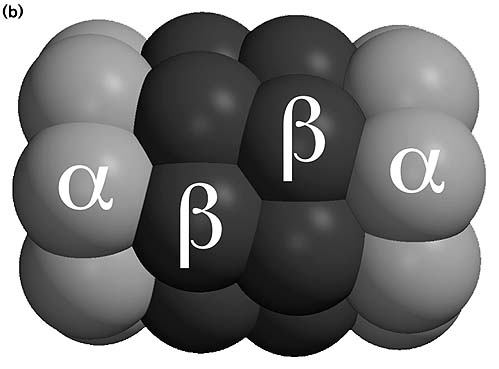

Now

that the proteins are ubiquitinated, it is necessary that these proteins are

broken down by a certain mechanism. This mechanism involves an 700 kD enzyme

[1]. This is not the

complete working proteasome, it is only the catalytic core and is called a 20 S

proteasome. This catalytic core is built up out of seven different a and seven different b

subunits. These a and b

subunits are arranged in four rings; each ring contains seven subunits: 7a/7b/7b/7a. So the rings containing seven a subunits are situated more at both ends

[1],[5].

[7]

[7]

The catalytic core contains two catalytic parts, each containing

both an a and a b

ring. The catalytic sites are situated inside the central cavity of the

catalytic core, and there the targeted proteins are broken down [1],[5].

The b subunits also have an important

feature: some of the b subunits are inducible by

Interferon-g (IFN-g).

These subunits can alter the peptidase activity of the whole proteasome. IFN-g is an antiviral factor, because it induces

the degradation of besides the old or faulty also the viral proteins; it works

by interacting on the special b subunits.

These subunits vary depending on the tissue; sometimes more and

sometimes less of these IFN-g-inducible b subunits are present.

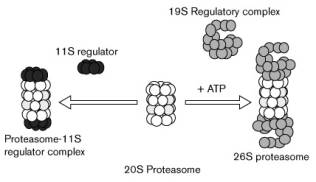

The degradation of faulty or old proteins is not only done by

the 20 S catalytic core; the ubiquitinated proteins also have to be detected

and this detection of the ubiquitin tag is done by a 19 S cap. The 19 S cap is

situated on both ends of the 20 S catalytic core [1,5].

[5]

[5]

The 19 S caps consist of about twenty subunits, of which some

have ATP-ase activity; this activity is used to unfold the protein and insert

it in one of the two catalytic cores.

The result of a 20 S proteasome and two 19 S caps is the fully

functional 26 S proteasome, a proteasome that both recognises and destroys

ubiquitintated proteins.

Except for the 19 S cap, another cap can also bind to the 20 S

core: the 11 S cap. This cap also regulates the protein degradation, but this

cap is induced by IFN-g.

The replacement of a 19 S cap by an 11 S cap results in altered peptidase activity [1,5].

The complete 26 S protease mechanism consists of a 700 kDa 20 S

catalytic core and two 900 kDa 19 S caps. The total weight of the

enzyme-complex thus is 2500 kDa [3].

This

26 S proteasome breaks the ubiquitinated proteins down in small peptides of

eight to ten amino acids,

which are released via small fenestrations in the proteasome [2]. These amino acids can later be presented to the outer

membrane of the cell, and sometimes the presented peptides evoke an immune

response. This can be very useful when the cell is infected by a virus: a great

amount of viral protein will be made and of course there will be produced viral

proteins which have a misfolded terminus, and thus are marked by the

ubiquitination mechanism. The ubiquitinated viral proteins will also be

presented as small peptides to the outer cell membrane and can there be

detected by the immune system; an immune response occurs.

This is an example of how the proteasome can be very useful

during viral infections, and this process is also regulated by IFN-g: not the 19 S, but the IFN-g-inducible 11 S cap regulates the process;

both ‘normal’ and viral proteins are broken down very fast. This is not

strange, because IFN-g is an antiviral protein and

during infection, the cell has to present the viral proteins very fast on the

outer membrane of the cell, so that the immune system can react immediately

[5].

The peptides that appear during the degradation of proteins have

to be presented on the outer cell membrane by a MHC class I molecule. I think

that the proteasome consisting of a 20 S catalytic core and two 11 S caps is

more situated near the Endoplasmatic Reticulum (ER), because the MHC class I

molecules are inside the ER.

But a problem arises when the proteins are being degradated and

the peptides are formed: how do these peptides get into the ER?

It has been found that these peptides are transported into the

ER by an ABC-transporter: the transporter associated with antigen processing

(TAP) [4]. I think that the proteasome is very near to this TAP and maybe it is

somehow connected to it, to deliver the peptides directly to the TAP.

After the peptides have been delivered by the TAP into the ER,

MHC class I molecules will take them up [5]. The MHC class I peptide complex

will be transferred to the outer cell membrane via the Golgi Apparatus.

Now it is clear that small peptides can be transported into the

ER; but considering that many of the misfolded proteins are still in the ER (where a great part of

the proteins is made), the question arises

how these non-cytoplasmic proteins are degradated.

This question could be easily answered if proteasomes existed

inside the ER, but that is not the case: most of the proteasomes are situated

in the cytoplasm, a part in the nucleus and a part is associated with the

membrane of the ER. Approximately 16 percent of the proteasomes in rat

hepatocyte cells are localised in the nucleus and 14 percent is associated with

the outside of the ER; the other 70 percent mostly is in the cytosol [5].

So the proteins that are (partly) inside the ER first have to be

detected to be broken down.

This is thought to be done by ER-resident chaperones such as

calnexins, which escort the proteins to sites where they can be ubquitinated.

This has been investigated in yeast cells;

the ubiquitination in the ER is done by Ubc-6 and Ubc-7 [1].

It is thought that the mechanism of escorting proteins and

ubiquitinating them in the ER functions the same in higher organisms.

So if the proteins are ubiquitinated, they are ready to be

broken down, but they are still (partly) inside the ER. This does not matter,

because the proteasome recognises the ubiquitine tag and when that is done, the

proteasome starts braking down the protein while it is pulling the protein out

of the ER and degradates it completely.

So now it is clear how proteins inside the ER and the cytosol

are degradated by the proteasomes. But how are the complicated structures of

the proteasome broken down? This can not be done by other proteasomes; the

proteasomes have to be broken down by something bigger than itself. It is

thought that they are degradated by lysosomes [5]. They take up the old

proteasomes and destroy them by making the inside of the lysosome acidous.

Now

it is clear that the mechanism of destroying the faulty or old proteins serves

many purposes: preventing the accumulation of useless proteins in the cell,

preventing the waste of amino acids and the presentation of parts of both own

and viral proteins.

Conclusion

At the start of this ‘mini-scription’ the main question was how

the proteins are marked for the degradation mechanism and in which way the

proteins are broken down by this mechanism.

The question now can be answered: the proteins ready for

degradation, whether they are old or just defective, are recognised by their

destabilising N-terminus. This N-terminus starts a cascade of enzyme reactions:

three different enzymes (E1, E2, E3) add an ubiquitin tag to the targeted protein.

This ubiquitin tag is than recognised by a proteasome and this proteasome

cleaves the proteins in peptides of eight to ten amino acids.

[7]

[7]

The exact mechanism of the cleavage of the proteins inside the

proteasome is still unclear and thus has to be investigated. I speculate that

specific amino acids in the protein better bind with some subunits of the

proteasome than with their neighbour amino acids; thus breaking the bond

between them and their neighbour(s). Now the amino acid has to be removed out

of the proteasome, I suggest that this is done by a ATP hydrolising reaction in

which the proteasome makes a twisting movement; the amino acid(s) are removed.

Further investigation is needed to understand how it really works.

In the near future the knowledge about the degradation of

proteins can be very useful in preventing several diseases, which are now very

hard to prevent or cure.

References

[1] Hirsch C. and Ploegh H.L. (2000) ‘Intracellular targeting of the proteosome’ trends in CELL BIOLOGY 10, pp. 268-271

[2] Hochstrasser M. (1995) ‘Ubiquitin,

proteasomes, and the regulation of intracellular protein degradation’ Current Opinion in Cell Biology 7, pp.

215-223

[3] Kirschner M. (1999) ‘Intracellular

proteolysis’ Trends in Cell Biology, vol.9, N°12

[4] Reits E.A.J., Vos J.C., Grommé M. & Neefjes J. (2000) ‘The major substrates for TAP in vivo are derived from newly synthesized proteins’ Nature 404, pp. 774-778

[5] Rivett A.J. (1998) ‘Intracellular distribution

of proteasomes’ Current Opinion in Immunology 10, pp. 110-114

[6] Schubert U, Anton L.C., Gibbs J, Norbury C.C., Yewdell J.W. & Bennink J.R. (2000) ‘Rapid degradation of a large fraction of newly synthesized proteins by proteosomes’ Nature 404, pp. 770-774

[7] Stock D., Nederlof P.M., Seemüller E., Baumeister W., Huber R., Löwe J. (1996) ‘Proteosome: from structure to function’ Current Opinion in Biotechnology 7, pp. 376-385

[8] The

illustration at the front-page is derived from the website of the ‘University

of Tours’ in France:

‘http://prolysis.phys.univ-tours.fr/Prolysis/proteasome.html’