PROTOTYPING

KINDS OF INFORMATION SOUGHT

Prototyping of information systems is a worthwhile technique for quickly gathering specific information about

users' information requirements. As will become evident in the second section

of this chapter, there are four basic approaches to prototyping. Generally

speaking, effective prototyping should come early in the systems development

life cycle, during the requirements determination phase. However, prototyping

is a complex technique that requires knowledge of the entire systems

development life cycle before it is successfully accomplished. Prototyping is

included at this point in the text to underscore its importance as an

information‑gathering technique. When using prototyping in this way, the

systems analyst is seeking initial reactions from users and management to the

prototype, user suggestions about changing or cleaning up the prototyped

system, possible innovations for it, and revision plans detailing which parts

of the system need to be done first or which branches of an organization to

prototype next. Figure 8.1 shows the four kinds of information that analysts

seek during prototyping.

INITIAL USER REACTIONS

As the systems analyst presenting a prototype of the

information system, you are keenly interested in the reactions of users and

management to the prototype. You want to know in detail how they react to

working with the prototype and how good the fit is between their needs and the

prototyped features of the system. Reactions are gathered through observation,

interviews, and feedback sheets (possibly questionnaires) designed to elicit

each person's opinion about the prototype as he or she interacts with it.

Through such user reactions, the analyst discovers many perspectives on the

prototype, including whether users seem happy with it and whether there will

be difficulty in selling or implementing the system.

User Suggestions

The analyst is also interested in user and management suggestions about refining

or changing the prototype that has been presented. Suggestions are garnered

from those experiencing the prototype as they work with it for a specified

period. The time that users spend with the prototype is usually dependent on

their dedication to and interest in the systems project. Suggestions are the

product of users' interaction with the prototype as well as their reflection on

that interaction. The suggestions obtained from users should point the analyst

toward ways of refining, changing, or "cleaning up" the prototype so

that it better suits users' needs. I

Innovations

Innovations for

the prototype (which, if successful, will be part of the finished system) are

part of the information sought by the systems analysis team. Innovations are

new system capabilities that have not been thought of prior to the time when

users began to interact with the prototype. These innovations go beyond the

current prototyped features by adding something new and innovative.

Revision Plans

Prototypes preview the future

system. Revision plans help identify priorities for what should be prototyped

next. In situations where many branches of an organization are involved,

revision plans help to determine which branches to prototype next.

Information gathered in the

prototyping phase allows the analyst to set priorities and redirect plans

inexpensively, with a minimum of disruption.

Because

of this feature, prototyping and planning go hand in hand.

APPROACHES TO PROTOTYPING

Kinds of Prototypes

The word prototype is used in many

different ways. Rather than attempting to synthesize all of these uses into one

definition or trying to mandate one correct approach to the somewhat

controversial topic of prototyping, we will illustrate how each of several

conceptions of prototyping may be usefully applied in a particular situation.

PATCHED‑UP PROTOTYPE. The

first kind of prototyping has to do with constructing a system

that works but is patched up or patched together. In engineering this approach

is referred to as bread boarding‑creating a patched‑together,

working model of an (otherwise microscopic) integrated circuit.

An example in information systems is a working model

that has all the necessary features but is inefficient. In this instance of

prototyping, users can interact with the system, getting accustomed to the

interface and types of output available. However, the retrieval and storage of

information may be inefficient, since programs were written rapidly with the

objective of being workable rather than efficient. A patched‑up prototype

may be envisioned as something like the illustration shown in Figure 8.2. Another

example of a patched‑up prototype is an information system that has all

the proposed features but is really a basic model that will eventually be

enhanced.

NONOPERATIONAL PROTOTYPE. The second conception of a

prototype is that of a nonworking scale model which is set up to test certain

aspects of the design. An example of this approach is a full‑scale model

of an automobile which is used in wind tunnel tests. The size and shape of the

auto are precise, but the car is not operational. In this case only features of

the automobile essential to wind tunnel testing are included.

A nonworking scale model of an information system

might be produced when the coding required by the applications is too extensive

to prototype but when a useful idea of the system can be gained through the

prototyping of the input and output only. This kind of prototype is shown

conceptually in Figure 8.3. In this instance processing, because of undue cost

and time, would not be prototyped. However, some decisions on the utility of

the system could still be made based on prototyped input and output.

FIRST‑OF‑A‑SERIES PROTOTYPE. A third conception of

prototyping involves creating a first full‑scale model of a system,

often called a pilot. An example is prototyping the first airplane of a series.

The prototype is completely operational and is a realization of what the

designer hopes will be a series of airplanes with identical features.

This type of prototyping is useful when many

installations of the same information system are planned. The full‑scale

working model allows users to experience realistic interaction with the new

system, yet it minimizes the cost of overcoming any problems that it presents.

This sort of prototype is depicted in Figure 8.4.

For example, when a retail grocery chain intends to

use EDI (electronic data interchange) to check in suppliers' shipments in a

number of outlets, a full‑scale model might be installed in one store in

order to work through any problems before the system is implemented in all the

others. Another example is found in banking installations for electronic funds

transfer. A full‑scale prototype is installed in one or two locations

first, and if successful, duplicates are installed at all locations based on

customer usage patterns and other key factors.

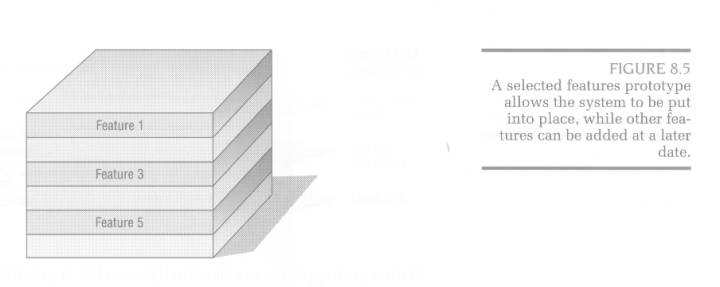

SELECTED FEATURES PROTOTYPE. A fourth conception of

prototyping concerns building an operational model that includes some, but not

all, of the features that the final system will have. An analogy would be a new

retail shopping mall that opens before the construction of all shops is

complete. In a newly opened retail mall, essential functions such as being able

to purchase some goods, eating in a fast‑food restaurant, and parking

nearby are possible, although not all space is occupied and not all goods that

will ultimately be for sale are available when the complex first opens. Nonetheless,

from initial contact with the retail complex, it is possible to gain a good

understanding of what future visits will be like. When prototyping information

systems in this way, some, but not all, essential features are included. For

example, a system menu may appear onscreen that lists six features: add a

record, update a record, delete a record, search a record for a keyword, list a

record, or scan a record. However, in the prototyped system, only

three of the six may be available for use, so that the user may add a record

(feature 1), delete a record (feature 3), and list a record (feature 5), as illustrated in Figure 8.5.

When this kind of prototyping is done, the system is

accomplished in modules, so that if the features that are prototyped are evaluated as successful, they can be incorporated into the

larger, final system without undertaking immense work in interfacing.

Prototypes done in this manner are part of the actual system. They are not just

a mock‑up as in the first definition of prototyping considered

previously.

Prototyping as an Alternative to the Systems Development Life Cycle

Some analysts argue that

prototyping should be considered as an alternative to the Systems development life, cycle (SDLQ. Recall that the SDLC, introduced

in Chapter 1, is a logical, systematic

approach to follow in the development of information systems. Complaints about

going through the SDLC center around two main concerns, which are interrelated.

The first concern is the extended time required to go through the development

life cycle. As the investment of ana1yst time increases, the cost of the delivered

system rises proportionately. The second concern about using the SDLC is that

user requirements change over time. During the long interval between the time

that user requirements are analyzed and the time that the finished system is

delivered, user requirements are evolving. Thus, because of the extended

development cycle, the resulting system may be criticized for inadequately

addressing current user information requirements.

It is apparent that the concerns are interrelated,

since they both pivot on the time required to complete the SDLC and the problem

of falling out of touch with user requirements during subsequent development

phases. If a system is developed in isolation from users (after initial

requirements analysis is completed), it will not meet their expectations.

A corollary of the problem of keeping up with user

information requirements is the suggestion that users cannot really know what

they do or do not want until they see something tangible. And in the traditional SDLC, it often is too late to change an unwanted system once it is

delivered.

To overcome these problems, some analysts propose

that prototyping be used as an alternative to the systems development life

cycle. When prototyping is used in this way, the analyst effectively shortens

the time between ascertainment of information requirements and delivery of a

workable system. Additionally, using prototyping instead of the traditional

systems development life cycle might overcome some of the problems of

accurately identifying user information requirements.

With a prototype, users can actually see what is

possible and how their requirements translate into hardware and software. Any

of the four kinds of prototyping discussed earlier might be used.

Drawbacks to supplanting the systems development

life cycle with prototyping include prematurely shaping a system before the

problem or opportunity being addressed is thoroughly understood. Also, using

prototyping as an alternative may result in producing a system which is

accepted by specific groups of users but which is inadequate for overall system

needs.

The approach we advocate here is to use prototyping

as a part of the traditional systems development life cycle. In this view

prototyping is considered as an additional, specialized method for

ascertaining users' information requirements.

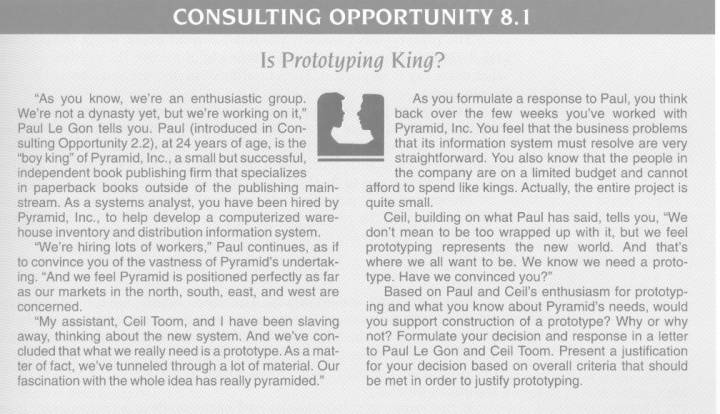

DEVELOPING A PROTOTYPE

In this section guidelines for developing a

prototype are advanced. The term prototyping is taken in the sense of the last

definition that was discussed that is, a selected‑features prototype

that will include some but not all features, one that, if successful, will

eventually be part of the larger, final system that is delivered. When

deciding whether to include prototyping as a part of the systems development

life cycle, the systems analyst needs to consider what kind of problem is

being solved and in what way the system presents the solution. Different types

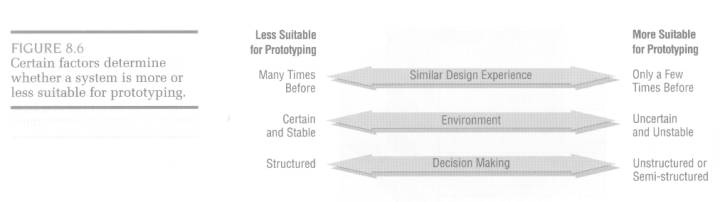

of systems and their suitability for prototyping are depicted in Figure 8.6. A straightforward payroll or

inventory system which solves a highly structured problem in a traditional

manner is not a good candidate for prototyping, because the outcome of the

system as a solution is well‑known and predictable.

Rather, consider the novelty and complexity of the

problem and its solution. A novel and complex system that addresses

unstructured or semi structured problems in a nontraditional way is a perfect

candidate for prototyping. Decision support systems, which are the subject of

Chapter 12, are personalized information

systems that support users in semi structured decision making. As such, DSSs

are well‑suited to prototyping.

The systems analyst must also evaluate the

environmental context for the system when deciding whether to prototype. If the

system will exist in an environment that is stable for long periods,

prototyping may be unnecessary. However, if the environment for the system

changes rapidly, then prototyping should be seriously considered. By their

nature prototypes are evolutionary and can absorb many revisions.

The prototype system is actually an operational

portion of the eventual system that you will build. It is not a complete

system, since you will

strive to build it quickly; only some essential

functions will be included in the model. However, it is important to envision

and then build the prototype as part of the actual system with which the user

will interact. It must incorporate enough representative functions to allow

users to understand that they are interacting with a real system.

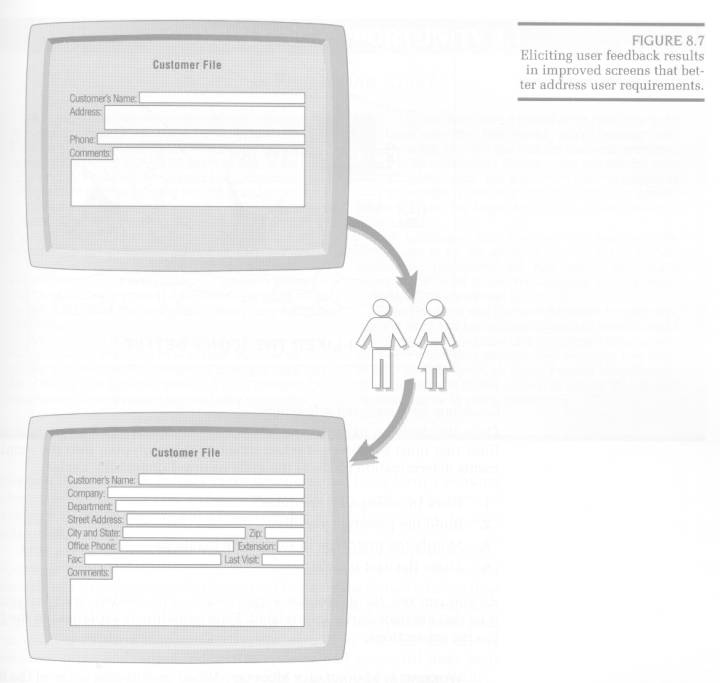

Prototyping is a superb way to elicit feedback about

the proposed system and about how readily it is fulfilling the information

needs of its users, as depicted in Figure 8.7.

The first step

of prototyping is to estimate the costs involved in building a module of the

system. If costs of programmers' and analysts' time, as well as equipment

costs, are within the budget, then building of the prototype can proceed.

Prototyping is an excellent way to facilitate the integration of the

information system into the larger system of the organization.

Guidelines for Developing a Prototype

Once the decision to prototype has been made, there

are four main guidelines that must be observed when integrating prototyping

into the requirements determination phase of the systems development life

cycle:

1. Work in manageable

modules.

2.

Build the prototype rapidly.

3. Modify the prototype in

successive iterations.

4. Stress the user interface.

As you can see, the guidelines suggest ways of

proceeding with the prototype that are necessarily interrelated. Each

guideline is explained in the following subsections.

WORKING IN MANAGEABLE MODULES. When prototyping some of the

features of a system into a workable model, it is imperative that the analyst

work in manageable modules. One of the distinct advantages of prototyping is

that it is not necessary or desirable to build an entire working system for prototype

purposes.

A manageable module is one that allows users to interact with

its key features yet can be built separately from other system modules. Module

features that are deemed less important

are purposely left out of the initial prototype.

BUILDING

THE PROTOTYPE RAPIDLY. Speed is essential to the successful prototyping

of an information system. Recall that one of the complaints voiced against following the traditional

systems development life cycle is that the interval between requirements

determination and delivery of a complete system is far too long to effectively

address evolving user needs.

Analysts can use prototyping to shorten this gap by using traditional

information‑gathering techniques to pinpoint salient information require‑

ments and then they can quickly make decisions that

bring forth a working model. In effect the user sees and uses the system very

early in the systems development life cycle instead of waiting for a finished

system to gain hands‑on experience.

After a brief analysis of information requirements

using traditional methods, such as interviewing, observing, and researching

archival data, the analyst constructs working models for the prototype. The

prototype should take less than a week to put together; two or three days is

preferable and possible. Remember that in order to build a prototype this

quickly, you must use special tools, such as an existing database management

system, as well as software that allows generalized input and output,

interactive systems, and so on. All these tools permit speed of construction

that is impossible with traditional programming.

It is important to emphasize that at this stage in

the life cycle, the analyst is still gathering information about what users

need and want from the information system. The prototype becomes a valuable

extension of traditional requirements determination. The analyst assesses user

feedback about the prototype in order to get a better picture of overall

information needs.

Putting together an operational prototype both

rapidly and early in the systems development life cycle allows the analyst to

gain valuable insight into how the remainder of the project should go. By

showing users very early in the process how parts of the system actually

perform, rapid prototyping guards against over committing resources to a

project that may eventually become unworkable.

MODIFYING THE PROTOTYPE.

A third

guideline for developing the prototype is that its construction must support

modifications. Making the prototype modifiable means creating it in modules

that are not highly interdependent. If this guideline is observed, less resistance

is encountered when modifications in the prototype are necessary.

The prototype is generally modified several times,

going through several iterations. Changes in the prototype should move the

system closer to what users say is important. Each modification necessitates

another evaluation by users.

As with the initial

development, modifications must be accomplished swiftly, usually in a day or

two, in order to keep the momentum of the project going. However, the exact

timing of modifications depends on how dedicated users are to interacting with

modified prototypes. Systems analysts must encourage users to do their share by

evaluating changes rapidly.

The prototype is not a finished system. Entering the

prototyping phase with the idea that the prototype will require modification is

a helpful attitude that demonstrates to users how necessary their feedback is

if the system is to improve.

STRESSING THE

USER INTERFACE. The user's interface with the prototype (and eventually the system) is

very important. Since what you are really trying to achieve with the prototype

is to get users to further articulate their information requirements, they must

be able to interact easily with the system's prototype. For many users the

interface is the system. It should not be a stumbling block. For example, at

this stage the goal of the analyst is to design an interface that both

allows the user to interact with the system with a minimum of training and

allows a maximum of user control over represented functions. Although many

aspects of the system will remain undeveloped in the prototype, the user

interface must be well developed enough to enable users to pick up the system

quickly and not be put off. On‑line, interactive systems using GUI

interfaces are ideally suited to prototypes. Chapter 18 describes in detail the

considerations that are important in designing the user interface.

Many of the intricacies of interfaces must be

streamlined or ignored altogether in the prototyping phase. However, if

prototype interfaces are not what users need or want or if systems analysts

find that the interfaces do not adequately allow system access, then they, too,

are candidates for modification.

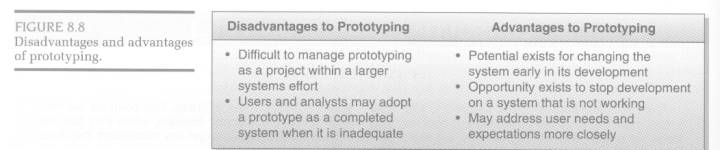

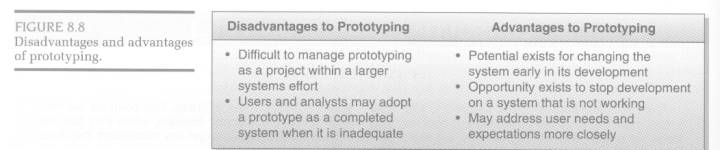

Disadvantages of Prototyping

As with any information‑gathering technique,

there are several disadvantages to prototyping. The first is that it can be

quite difficult to manage prototyping as a project within the larger systems

effort. The second disadvantage is that users and analysts may adopt a

prototype as a completed system when it is in fact inadequate and was never

intended to serve as a finished system.

The analyst needs to weigh those disadvantages

against the known advantages when deciding whether to prototype, when to

prototype, and how much of the system to prototype.

MANAGING THE

PROJECT. All

of the systems analysts' management skills that you learned in Chapter 3 come

into play again as your systems analysis team constructs and modifies a

prototype. All of the possible problems that project management is subject to are

relevant here.

Although several iterations of the prototype may be

necessary, extending the prototype indefinitely also creates problems. It is

important that the systems analysis team devise and then carry out a plan

regarding how feedback on the prototype will be collected, analyzed, and

interpreted. Set up specific time periods during which you and management

decision makers will use feedback to evaluate how well the prototype is

performing. Even though the prototype is prized for its evolutionary nature,

the analyst cannot permit prototyping to overtake other phases in the systems

development life cycle.

Elicit feedback from users periodically, not just

once, and ask them if previous suggestions for improvements or changes have

been acted upon satisfactorily. Feedback is directed to the members of the

systems analysis team for their reaction and possible modification of the

prototype to better-fit user needs. Recall that modifications to the prototype

should be managed on a tight schedule of only a day or two each throughout the

successive iterations.

ADOPTING AN INCOMPLETE SYSTEM AS COMPLETE. A second major disadvantage

of prototyping is that if a system is needed badly and welcomed readily, the

prototype may be accepted in its unfinished state and pressed into service

without the necessary refinements. While superficially, this may seem to be an

appealing way to short‑cut the development effort, it works to the

business' and team's disadvantage.

Users will develop interaction patterns with the

prototype system that are not compatible with what will actually occur with the

complete system. Additionally, a prototype will not perform all necessary

functions. Eventually, when users discover the deficiencies, user backlash may

develop if the prototype has been mistakenly adopted and integrated into the

business as if it were a complete system.

Advantages of Prototyping

Prototyping is not necessary or appropriate in every

systems project, as we have seen. However, the advantages should also be given

consideration when deciding whether to prototype. The three major advantages of

prototyping are: the potential for changing the system early in its

development, the opportunity to stop development on a system that is not

working, and the possibility of developing a system that more closely addresses

users' needs and expectations. All three advantages are interrelated.

CHANGING THE SYSTEM EARLY IN ITS DEVELOPMENT. Successful prototyping

depends on early and frequent user feedback, which can be used to help modify

the system and make it more responsive to actual needs. As with any systems

effort, early changes are less expensive than changes made late in the

project's development.

Since the prototype can be changed many times and

since flexibility and adaptation are at the heart of prototyping, the feedback

that calls for a change in the system is often the action taken. Feedback will

help tell you if changes are warranted in the input, process, or output areas,

or if all three need adjustment.

When changing a prototype, analysts do not need to

worry about wasting many man‑hours of their efforts and those of

programmers who have developed a full‑blown system only to find that it

needs modifications. Although the prototype represents an investment of time and

money, it is always considerably less expensive than a completed system.

Concomitantly, system problems and oversights are much easier to trace and

detect in a prototype with limited features and limited interfaces than they

are in a complex system.

SCRAPPING UNDESIRABLE SYSTEMS. A second advantage of using

prototyping as an information‑gathering technique is the possibility of

scrapping a system that is just not what users and analysts had hoped it would

be. Once again, the issue of time and money arises. A prototype represents much

less of an investment than a completely developed system.

Permanently removing the prototype system from use

is done when it becomes apparent that the system is not useful and does not

fulfill the information requirements (and other objectives) that have been

set. Although scrapping the prototype is a difficult decision to make, it is

infinitely better than putting increasing sums of time and money into a project

that is plainly unworkable.

DESIGNING A SYSTEM FOR USERS' NEEDS AND

EXPECTATIONS. A

third advantage of prototyping is that the system being developed should be a

better fit with users' needs and expectations. Many studies of failed

information

systems indict the long interval between

requirements determination and the presentation of the finished system; these

systems failed precisely because it is

common for

systems analysts to develop systems while sequestered away from users during

this critical period.

It is a better practice to

interact with users throughout the systems development life cycle. If your

team makes a commitment to ongoing user involvement in all phases of the

project, then the prototype can be used as an interactive tool that shapes the

final system to accurately reflect users' requirements.

Users who take early ownership of the information

system work harder to ensure its success. One way to foster early user support is to involve users actively in prototyping.

If your evaluation of the prototype indicates that

the system is functioning well and within

the guidelines that have been set, the decision should be to keep the prototype

going and continue expanding it to include other functions as planned. This,

then, is considered an operational prototype. The

decision is made to keep the prototype

functioning if the prototype is within the budget set for

programmers' and analysts' time, if users find the system worthwhile, and if it

is meeting the information require‑

ments and objectives that have been set. A list

comparing disadvantages and advantages of prototyping is given in Figure 8.8.

USERS'ROLE IN PROTOTYPING

The users' role in prototyping can be summed up in

two words: honest involvement. Without user involvement there is little reason

to prototype. The precise behaviors necessary for interacting with a prototype

can vary, but it is clear that the user is pivotal to the prototyping process.

Realizing the importance of the user to the success of the process, the

members of the systems analysis team must encourage and welcome input and

guard against their own natural resistance to changing the prototype.

Interaction with the Prototype

There are three main ways a

user can be of help in prototyping:

1. Experimenting with the

prototype

2. Giving open reactions to the

prototype

3. Suggesting additions to

and/or deletions from the prototype

All of the foregoing stem from the users' initial

and successive interactions with the prototype.

EXPERIMENTING

WITH THE PROTOTYPE. Users should be free to experiment with the prototype. In contrast to a

mere list of systems features, the prototype allows users the reality of hands‑on

interaction. Mounting a prototype on an interactive Web site is one way to

facilitate this interaction. Limited functionality along with the capability to

send comments to the systems team can be included.

Users need to be encouraged to experiment with the

prototype. The final system will be delivered with documentation stating how

the system is to be used, and this in effect constrains experimentation. But in

the prototyping stage, the user is free from all but minimal instruction on

how to use the system. When this is the case, experimentation becomes necessary

to make the prototype work.

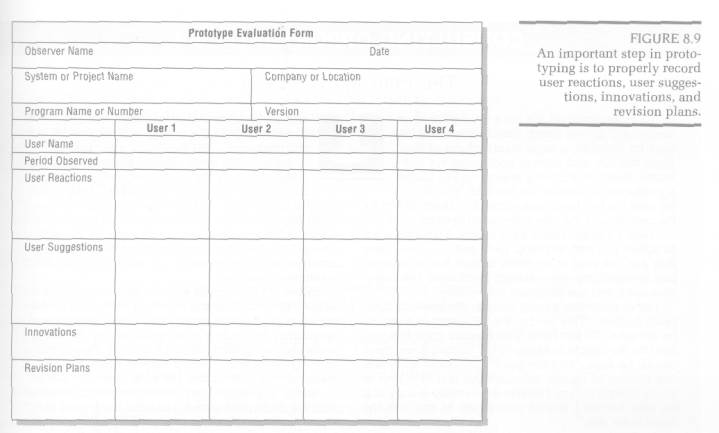

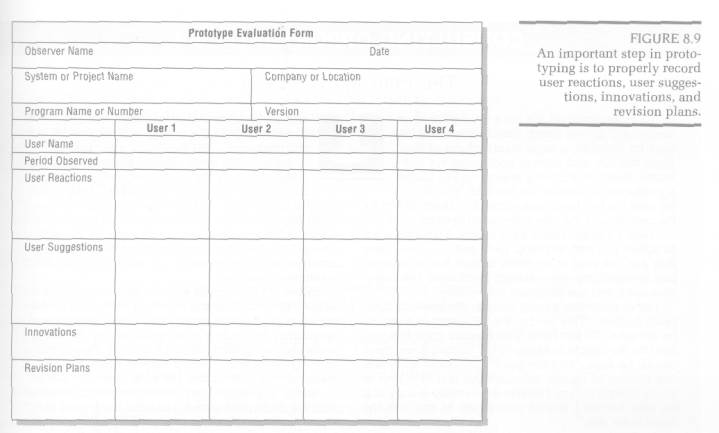

Analysts need to be present at least part of the

time when experimentation is occurring. They can then observe users'

interactions with the system, and they are bound to see interactions they never

planned. A form for observing user experimentation with the prototype is shown

in Figure 8.9. Some of the variables you should observe include user reactions

to the prototype, user suggestions for changing or expanding the prototype,

user inno‑

vations for using the system in completely new ways,

and any revision plans for the prototype that aid in setting priorities. When

revising the prototype, analysts should circulate their recorded observations

among team members so that everyone is fully informed.

GIVING OPEN REACTIONS TO THE PROTOTYPE. Another aspect of the users'

role in prototyping requires that they give open reactions to the prototype.

Unfortunately, this is not something that occurs on demand. Rather, making

users secure enough to give an open reaction is part of the relationship between

analysts and users that your team works to build.

Additionally, if users feel wary about commenting on

or criticizing what may be a pet project of organizational superiors or peers,

it is unlikely that open reactions to the prototype will be forthcoming.

Providing a private (relatively unsupervised) period for users to interact with

and respond to the prototype is one way to insulate them from unwanted

organizational influences. An exclusive Web site set up for users and analysts

can also help in this regard.

SUGGESTING CHANGES TO THE PROTOTYPE. A third aspect of the users'

role in prototyping is their willingness to suggest additions to and/or

deletions from the features being tried. The analysts' role is to elicit such

suggestions by assuring users that the feedback they provide is taken

seriously, by observing users as they interact with the system, and by

conducting short, specific interviews with users concerning their experiences

with the prototype.

Although users will be asked to articulate

suggestions and innovations for the prototype, in the end it is the analyst's

responsibility to weigh this feedback and translate it into workable changes

where necessary. Users need

to be encouraged to brainstorm about possibilities

and to be reminded that their input during the prototyping phase helps

determine whether to save, scrap, or modify the system. In other words users

should never be resigned to accepting in the prototype stage something less

than what they want. Systems analysts must remember to stress to users and

management alike that prototyping is the most appropriate time for system

changes.

In order to facilitate the prototyping process, the

analyst must clearly communicate the purposes of prototyping to users, along

with the idea that prototyping is valuable only when users are meaningfully

involved.

Prototyping and the "Year 2000

Crisis"

It seems so easy to type in a year as 97 or 98 instead of entering 1997 or 1999. It also saves a lot of

valuable space in a database and everything fits better oil a computer screen.

This was the standard way of thinking in the early

days of computing and is still the case even now. Banks encouraged the practice

by putting 19 on checks so their customers wouldn't have to write in the 19.

In the late 1990s programmers started to question whether this was a

good idea. After all, what happens in the year 2000. Will users want to see the 00 appear on the screen

or report?

When we calculated a person's age in 1996, we took 1996 ‑ 1975 = 21. That is, if you were born in

1975 you turned 21 on your birthday in 1996. If we only stored the last 2 digits, the calculation was 96 ‑ 75 = 21 years old.

Let's try the same in the year 2000. Take 2000 ‑ 1979 and the answer is also 2 1, but take 00 ‑ 79 and the answer is ‑ 79

or minus 79 years old. This is part of

the year 2000 crisis as well.

Prototyping can help determine problems such as

this. When you develop a prototype, make sure you encourage users to give

constructive criticism. In this way some problems, like the year 2000 crisis, may be averted.

SUMMARY

Prototyping is an information‑gathering

technique useful for supplementing the traditional systems development life

cycle. When systems analysts use prototyping, they are seeking user reactions,

suggestions, innovations, and revision plans in order to make improvements to

the prototype and thereby modify system plans with a minimum of expense and

disruption. Systems that support semi structured decision making (as decision

support systems do) are prime candidates for prototyping.

The term prototyping carries several different

meanings, four of which are commonly used. The first definition of prototyping

is that of constructing a patched‑up prototype. A second definition of

prototyping is a nonoperational prototype that is used to test certain

features of the design. A third conception of prototyping is creating the first‑of‑a‑series

prototype that is fully operational. This kind of prototype is useful when many

installations of the same information system (under similar conditions) are

planned. The fourth kind of prototyping is a selected features prototype that

has some, but not all, of the essential system features. It uses self‑contained

modules as building blocks, so that if prototyped features are successful, they

can be kept and incorporated into the larger, finished system.

The four major guidelines for developing a prototype

are to: (1) work in manageable modules, (2) build the prototype rapidly,

(3) modify the prototype, and (4) stress

the user interface.

One disadvantage of prototypes is that managing the

prototyping process is difficult because of the rapidity of the process and its

many iterations. A second disadvantage is that an incomplete prototype may be

pressed into service as if it were a complete system.

Although prototyping is not always necessary or

desirable, it should be noted that there are three main, interrelated

advantages to using it: (1) the

potential for changing the system early in its development, (2) the opportunity to stop

development on a system that is not working, and (3) the possibility of developing

a system that more closely addresses users' needs and expectations.

Users have a distinct role to play in the

prototyping process. Their main concern must be to interact with the prototype

through experimentation. Systems analysts must work systematically to elicit

and evaluate users reactions to the prototype. Sometimes this can be

accomplished by mounting the prototype on an interactive Web site that permits

users to see limited functionality and to enter comments for the systems team.

Analysts then work to incorporate worthwhile user suggestions and innovations

into subsequent modifications.