LOGARITHMS AND MULTIPLICATIVE EFFECTS

Multiplicative Symmetry: A Second Look

In our discussion of histograms earlier in

this chapter we showed that some variables have multiplicatively svmmetric

distributions. We stated, without any justification, that the logarithmic

transformation of some variables has a distribution that exhibits ordinary

symmetry. The reason for this is not hard to Understand if you recall one

key fact about logarithms; the logarithm of the product of two or more

numbers is the sum of their logarithms.

Thus, for example, log(a*b*c) = log(a) + log(b)

+ log(c) .

This is true whether you are using so-called

natural logarithms (logarithms to the base e, where e - 2.71828, approximately),

or logarithms to the base 10. You should convince yourself, using a spreadsheet

or a calculator, that

log(2+3*4) = log(2) + log(3) - log(4)

for both natural logarithms and logarithms

to the base 10.

Distributions that are multiplicatively symmetric

often arise when value of each observation is the product of a number of

small random effects. The logarithm of such a value will then be the sum

of a number of small random effects and the distribution of such a set

of values is lNely to be symmetric. Thus, logarithms convert or transform

multiplicative effects into additive effects.

Multiplicative Seasonals and Constant Growth

Rates

If you turn backto Figure 1.7, the graph of

retail sales over time, you will notice that the amplitude of the swings

behvesm the December peak and the JanuaryFebruary trough seems to get larger

over time. One possible explanation is that the seasonal effect is multiplicative.

Supposse, for example, that every December tends to be 20% above normal

and every January 15% below normal, then the difference between December

and January will be larger for high levels of sales, and smaller for low

levels. Because the level of sales has been increasing over time, the differences

will therefore get larger over time. If the seasonal effect of each months,

in fact, a constant multiple of some Normal level of sales, then a graph

showing a time series of the logarithm of sales will depict seasonal effects

that add to or subtract from normal the same constant amount for each month:

on the logarithmic scale, the seasonal effects will not change with tile

level of the series. Figure 1.14 shows such a graph, it seems to confirm

the multitalicative-seasorial hypothesis.

A constant . growth rate means that successive

values in a time series are constant multiples of preceding values. For

instance, if a variable increases by 5% per year, each year's value will

be 1.05 times the preceding year's. If this is so, the logarithm of the

values in the time series will have values that are constant increments

above preceding values, and therefore a graph of the logarithmic series

will have a shape close to a straight line. The U.S. population, the consumer

price index, gross national product, and electric power generation all

exhibit patterns of multiplicative growth over sufficiently long periods

of time. The values increase at an increasing rate, often described as

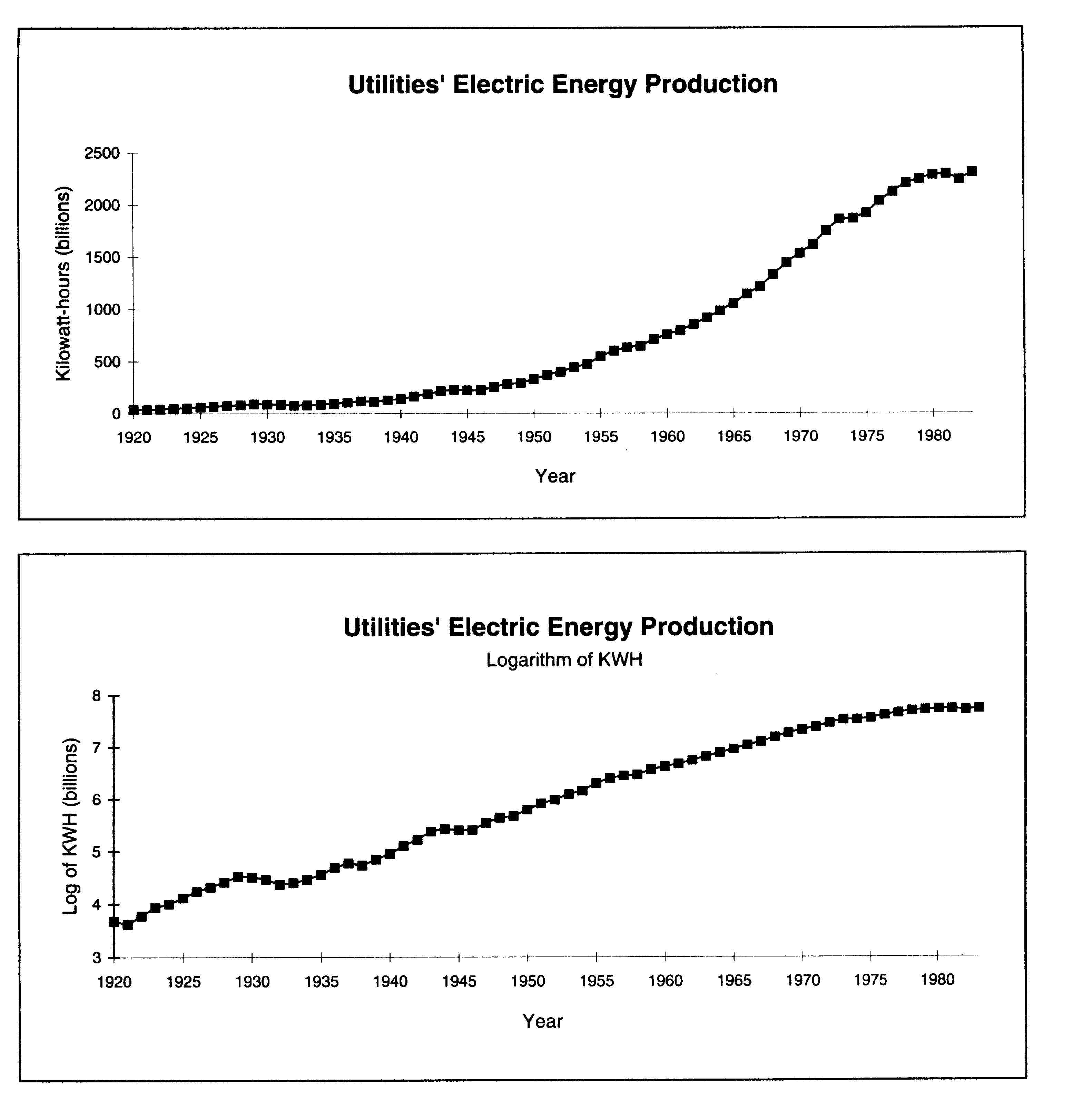

exponential growth. Figure 1.15, a graph of electric energy production

in the United States from 1920 to 1983, exhibits this kind of exponential

growth, at least through the mid-1970s. Figure 1.16, a graph of the logarithm

of the series, is more nearly linear. Notice that by "linearizing" the

series we can more easily detect the effects of the 1930s depression, the

end of World War 11, and the OPEC oil crisis of the 1970s on energy production.

Multiplicative Effects in Cross-Sectional Data

Even in cross-sectional data, the values of

a variable may depend on the values of other variables in a multiplicative

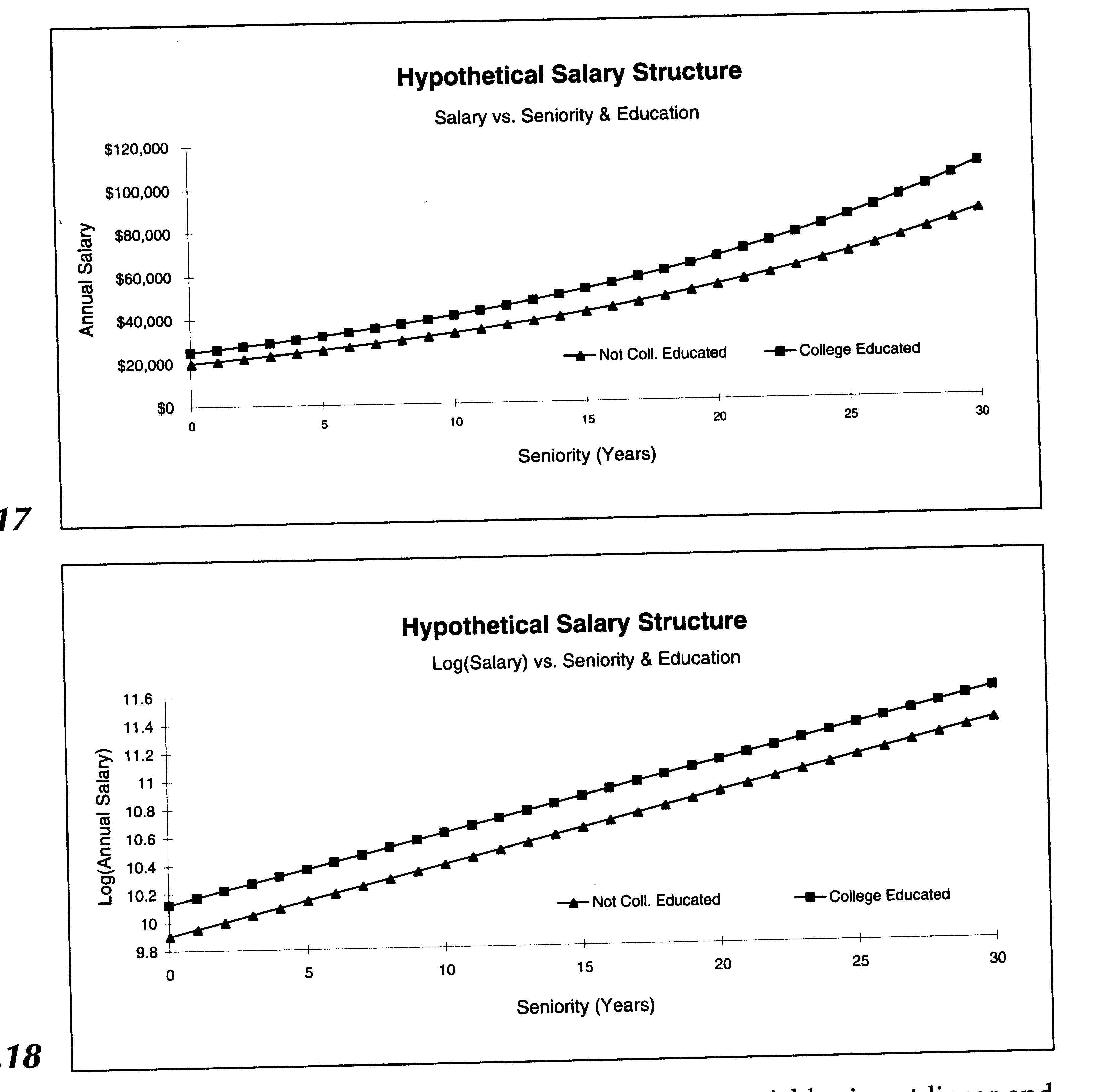

way. A companys salary structure may reward seniority and education, among

other things. Suppose that in a given year starting salary for a person

without a college education is $20,000, that college-educated employees

earn 25% more than employees with comparable seniority, and that each year

of seniority confers 5% more salary. Figure 1.17 shows what salaries would

be if there were no additional factors affecting salary. Figure 1.18 shows

the effects of seniority and education on log(salary). For a given level

of seniority, education adds the same amount to log(salary), no matter

what the level of seniority; we say that the effect of education on log(salary)

is multiplicative. When we look at the effect of seniority on log(salary)

for either level of education, we observe that it is linear, and this implies

that the effect of seniority on salary is multiplicative.

In general, when the relationship between two variables is not linear

and the dependent variable is measured on a ratio scale, it is a good idea

to see whether effects can be more simply explained by looking at graphs

of the logarithm of the dependent variable. A logarithmic transformation

of a ratioscale dependent variable may:

* produce a symmetric, rather than a skewed, distribution of the

dependent variable.

* produce a linear and additive relationship between the independent

variables and the transformed dependent variable, if the effects on the

natural dependent variable were multiplicative.

In performing transformations on our data, such as a log transform,

we trade off complexity to get simplicity in the form of straight lines

and additive effects.

Graphs with Logarithmic Scales

Ordinary graphs are plotted on an arithmetic scale, so that each

increment on an axis represents equal distance (i.e., the distance from

1 to 2 is the same as the distance from 2 to 3). Sometimes graphs are plotted

on a ratio or logarithmic (log) scale, in which equal distances represent

equal percent changes (i.e., the distance from 1 to 2 is the same as the

distance from 2 to 4).

Figures 1.19A-C show three different ways of plotting monthly values

of the Standard,and Poors 500 Stock Index, from January 1968 through January

1993. Part A shows values of the Index on an arithmetic scale, B shows

values of log (Index) on an arithmetic scale, and C shows values of the

Index on a log scale.13 Both B and C are essentially the same graphs: when

you want to capture multiplicative effects of a ratio-scale variable graphically,

graphs of either sort are equally appropriate.

Notice that both the B and C graphs convey a great deal more information

about stock-market fluctuations than does A. Looking at A, for example,

it appears that the major stock-market declines occurred during the crash

of 1987 and prior to the Gulf War in late 1990. Both B and C show, however,

that the percentage decline from 1969 to 1970 was as severe as-though more

protracted than-the 1987 crash, while the decline from late 1972 to late

1974 was substantially more severe than the crash.