HTML format Copyright © 1998 Louis S. Alfano

All rights reserved.

A CHINESE NEW YEAR'S DAY IN AMERICA

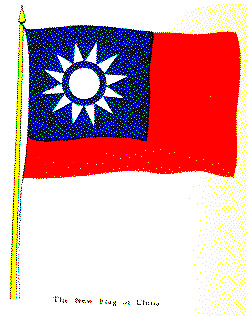

Chinese Flags, the Sun Flag -

After the Republic was announced in 1911, there was noticeable in San Francisco's Chinatown a

new flag, with crimson field, having on a blue background in the upper left-hand corner, a sun

with twelve rays. Wishing to buy a sun flag in Oakland, I was directed to a small, somewhat

obscure Chinese store on a railroad street. The Chinaman who sold it to me said that he had none

of the former yellow dragon-flags of China. However, going behind his counter, he did find, in

some nook, one of the tiny yellow silk flags of a few inches, representing the dragon with his

mouth open, ready to swallow the usual red ball. Coming back, he handed me this emblem of the

Manchu regime.

"How much is it?" I asked.

In very broken English he replied, "I not charge anything. Nobody want that flag now! We got flag like American flag!"

Some weeks before the Chinese New Year of 1912, the store windows in San Francisco's Chinatown were made gay by pictures of war scenes in China. The pictures were somewhat like the colored supplements of our American newspapers, but were Chinese-y, gorgeous with red and blue and yellow, with great white puffs representing cannon or rifle smoke. The Chinese revolutionary flag in the pictures was bright red, with a ring of nine yellow stars around a yellow sun, probably the flag of a certain district in China.

But we were to see greater marvels in the way of flags. The 17th of February, 1912, was Chinese New Year. As I lay awake in the early morning in Oakland, I heard the sound of fire-crackers set off by the usually very quiet Chinamen living in the humble little house in the hollow in the next block. Chinese New Year, as the world knows, has usually come on the first new moon after the sun crosses the constellation of Aquarius. In 1911, Chinese New Year fell on January 29th and the Chinese Baptist brethren in San Francisco held a New Year's "watch meeting."

Inasmuch as the rumor had gone forth that Dr. Sun Yat Sen had changed the Chinese calendar to correspond with that of civilized nations, and that February 17, 1912, would be the last of the ancient Chinese New Years, I went to San Francisco to see once more such a celebration as has been customary there in Chinatown. But by this time Yuan Shi Kai was President of China, and I was to see something new.

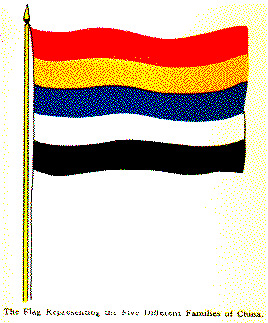

The Flag of Five Stripes -

As I climbed the street from the ferry toward San Francisco's Chinatown, what was that big flag

that floated from the tall flagstaff above the greensward across a square? Never had I seen that

flag before! It was of five stripes, each the length of the flag, each stripe a different color - red,

yellow, white, blue, black. What did it mean? All Chinatown was a-flutter with flags, most of

them the sun-flag and the United States flag, but here and there was that strange new flag, with

its stripes of red, yellow, white, blue, and black. A new flag had arisen! What did it mean?

Vainly I sought information, Queueless Chinatown was gay with its great balloon-like red-and-yellow glass lanterns. Little street-stands stood ready for business, though Chinese stores were observing their accustomed New Year's respite from trade. Now and then came the deafening explosion of fire-crackers.

Before turning into the heart of the celebration, I appealed to a young Chinaman for information about the new flag, but though willing to talk, he only knew what the sun-flag meant. The twelve points of the sun-flag, he explained, the sun "go around every day," and the blue of the sun-flag was the sky. But he did not know what the new flag of five stripes meant.

Along the sidewalks of Chinatown, I diligently sought knowledge. Behind the counter of a vegetable store I appealed to a Chinese-looking person.

"I don't know. I never use that flag," he answered.

Evidently the flag was very new. On the street-stands, various kinds of Chinese candy were for sale and brown li-chi nuts, with their soft, easily broken shells, and prune-like flesh; there were brown ovals of abalone meat, with rims of deeper brown, taken from the iridescent shells of the haliotis. There were great pale yellow pomelos, like pear-shaped grapefruit; there were tiny red goldfish, swimming in a glass bowl; there, next to the side-walk's edge, was a fence-like row of upright lengths of sugar-cane, five feet high perhaps, each length having been daubed with red clay on either end to prevent the escape of juice. High up somewhere could be heard the squeak of Chinese music, and the loud, steady clash of a Chinese gong or cymbals. Someone threw a bunch of lighted fire-crackers from an upper window into the middle of the street, where it exploded, frightening a horse into hysterics.

I resolved that I must have one of those strange new five-striped flags. They meant something, even if I had not found out what it was. But it wsa one thing to resolve to buy an another to accomplish it, on Chinese New Year. At a street-stand, a young Chinese who had used a five-striped flag as a decoration for his stand told me I could buy the flags in the next block. So I went on searching. A Chinaman who was out paying New Year's calls, opened the closed door of a store, and I followed him in. In the store were two Chinese shop-keepers.

"Hola! Hola!" the two storekeepers and their Chinese visitors greeted one another, but no attention was paid to me.

Each Chinaman had taken hold of his own hand, according to Chinese methods of greeting. Now, one of the other hosts took a white vessel like a tea-pot from inside another vessel on the counter, and poured something - whether tea or other liquid - into a sort of white goblet, from which the visiting Chinaman drank.

"Hola! Hola! Hola!" cried the guest and the hosts in a chorus of goodwill.

Out went the visiting Chinaman, and I wsa left to explain my presence. Probably the storekeepers had no flags. At least they professed so, and I went back to the street.

At length, discouraged by my fruitless efforts, I returned to my Chinese adviser of the street-stand.

"I can't buy a flag," I said. "You sell yours?"

No, he did not wish to sell his. But with a kindness that I could not have asked from him, the young Chinaman left his street-stand with his companion, and went into one of the stores. He said something in Chinese to the proprietor who did not bestir himself to sell me, but allowed the young man to go to a fat bundle of the very flags I had wanted. So paying twenty-five cents, I came out the possessor of a five-striped flag. At last, a portly, dignified, intelligent Chinese merchant to whom I appealed, told me the meaning of my flag. The five stripes meant the five families of China. He began naming them, beginning at the red stripe and taking the colors in order.

"Manchu," said he, meaning Manchuria, "Mongolia, China, Thibet and Chinese Turkestan."

The Joss House -

The strains of "Columbia, the gem of the ocean" sounded near by. It was played by a brass band

of young Chinese men dressed in American clothes and was attracting many Chinese listeners.

On the building before which they played was a sign inviting visitors to the joss-house upstairs. I

wished very much to visit the joss-house, but I hardly liked to go up alone. An American woman

with two little children was near me on the street. She agreed to go with me into the joss-house.

The band had gone up the first stairway, and had entered a Chinese society's rooms on the second floor. As we mounted the stairway, the woman and I spoke of the great changes among the Chinese, and I said that I hoped China would yet be a Christian nation.

"Don't you believe it!" burst out the woman with a sudden sharp decision. "They never will! They've got a good religion already! There isn't much difference between them and us. They've got one good religion and they don't live up to it, and we've got another good religion and we don't live up to it!"

Could I stop there on the narrow stairway, in the blare of San Francisco's Chinese New Year, with Chinese above us and Chinatown around us, to argue with her as to the fact that many a Chinaman has been changed by the power of God, so as to live and die for Christ? What did she know of the sturdy faithfulness of the Chinese Christian martyrs of 1900? Or, to come nearer home, what did she know or care concerning that zealous San Francisco Baptist Chinese preacher, Rev. Ko Chow, whose Christian devotion knew no bounds? For seven years, Rev. Ko Chow was a street evangelist among his Chinese people in San Francisco, till, on May 13, 1911, he was shot by a Chinese assassin and died the following day, to the great grief of the little Chinese church. Honored and faithful missionary, loved by all who knew him, Ko Chow, who was born in China, converted at Pacific Grove, California, baptized in the Pacific Ocean, and who labored for the salvation of the Chinese of southern California before beginning his almost nightly meetings on San Francisco's Chinese streets, was sufficient answer to any American unbelief.

At the first landing of the building, a group of Chinese men stood outside the rooms of the Chinese company, pressing in at the glass doors to see the Chinese band play. The woman paused here.

"I want to see the band play," she said.

So I left her with the Chinamen, for not thus would I give up my visit to the joss-house on the third floor.

At the next landing, a solitary Chinaman who was apparently in charge met me with a grave appearance and allowed me to walk in. I took him to be the priest of the joss-house, but I afterward learned that the head men among the Chinese officiate as priests, there being very few, if any, real Chinese priests here.

I thought myself alone with the somewhat elderly Chinaman, but afterwards I caught sight of several Chinamen outside the window, on the balcony overlooking the street. The emptiness of the joss-house contrasted with the crowds, the blare, and the explosions and smoke of the firecrackers in the street below.

The old Chinaman followed me. The object to which my eyes were first attracted was a large representation of a man's head with a black beard. The head was across the room in a corner, and may have been made of wood or wax, colored to represent the human face. In a receptacle before it were unlit punk-sticks. A small light was burning. With a dim notion that the black-whiskered head might represent Confucius or some other worth, I said to the supposed priest, "Who is that?"

"God," he answered promptly.

Next this representation of deity stood a large gong or bell in a frame, no doubt used to call the attention of the god to the worshiper, or perhaps to be used in this worship. A sign in English met my eyes: "TAKING PHOTOGRAPHS PROHIBITED ON THIS FLOOR."

I thought that the priest had left me to look around as I pleased, so I took out a pencil and paper, and was jotting down something, when I heard his voice at my side.

"What you make?" he demanded.

I explained that I was writing down some of the things that I saw, so that I could tell of them to my friends. The priest kept near me during my further investigations.

In the back part of the room I saw a Chinaman worshiping at a side-shrine near the back stairway. He did not kneel while I saw him, but, standing with his back toward me, he bowed three times to the object of his adoration.

At the back of the joss-house there was a large shrine, and I went to it, the ever-watchful priest at my side. Here lay some red divining-blocks. These were each about a foot long, on side of a block being flat and the other oval. The Chinaman who wishes to divine whether a plan of his will be lucky or not, throws the blocks and according to the way in which they fall, he judges the omen to be good or ill. The fortunate way is said to be that one block shall fall with the flat side up, and the other block with the curved side uppermost. Though I was quite certain what they were, I indicated the blocks and said to the priest: "What is that?" and he answered: "Good luck."

On the front of the larger shrine were offerings of food and a light was burning. Away at the back part of the shrine was another representation of a human head. I said to the priest, "Who is that?"

"God," again came the answer.

Would the woman whom I left at the lower landing still have declared that the Chinese had a "good religion"?

I returned to the front entrance. The priest said something. He has a little counter on the landing. He went behind the counter, and I waited, supposing he was going to show me something. He brought out in a paper case a little package of punk-sticks such as are burned before idols. He wished me to buy the punk-sticks for twenty-five cents. I courteously told him that I did not wish to buy them, and he let me go. Again, I was on the bare, narrow stairway.

A roar of fire-crackers arose. The Chinese band was coming out of the society's rooms, and I went down the stairs with them, the air chokingly full of blue smoke from the fire-crackers. Outside, the young Chinese band gathered once more and played "Marching through Georgia," as if they had been whiteskinned.

It has been said that in times past there were eighty-five of these Chinese joss-houses in California. Nevertheless, they are doomed to pass. A freind of mine told me that in northern California there was a joss-house containing some large idols, which the Chinese were almost ready to give away, were it not for two or three old Chinamen who objected. This loss of faith in idols does not, however, imply an acceptance of Christianity. There is, rather, somewhat of a tendency toward agnosticism among Chinese who cease to hold belief in the religion of their fathers. I once found an indication of this in going into a Chinese shop to buy a Japanese flag. I spoke to the Chinese shop-keeper about the anniversary of Wucheng. I told him that I hoped that China would become a Christian nation, and he answered that he thought that everything would change in China now. He agreed with me that after a while there would be no joss-houses left. From his manner of speaking, I thought perhaps he was a converted Chinaman, so I asked him if he were a Christian. No, he was not.

"Do you pray to Joss?" I asked.

"No," he said smiling.

"What do you do?" I asked.

"Nothing," he said, still smiling. "I go my way, my wife and children they go theirs. I am too old to change."

The Anniversary of Wucheng -

At the time of the first anniversary of Wucheng, September 28, 1912, while passing through a

street in Oakland's Chinatown, I noticed some new Chinese flags. Stopping to question a

Chinaman, who had just fastened a flag to his store door, I asked the reason for the decoration,

and he said "Chinese holiday."

"What holiday?" I persisted.

Summoning his meager English, he explained: "China Republic."

"Yes," I encouraged.

"One year," he said.

It did not seem a year to me. Was not the Chinese republic established on February 12, Lincoln's birthday? But something was being celebrated this September, and I went to San Francisco to discover what it was. There I found the San Francisco Chinese celebrating. Across Grant avenue, near Saint Mary's church stretched a white banner, edged with the other colors of the Chinese flag of the republic - red, yellow, blue and black. Across the upper part of the banner were Chinese characters, and below them were the English words, "The First Anniversary of Wucheng."

Into St. Mary's little square, opposite the church, young Chinese boys, belonging to two brass bands, were crowding, arranging themselves to be photographed. There was a large five-striped Chinese flag, an American flag and numerous white banners with Chinese or English inscriptions, of which this was one:

"LONG LIVE THE CHINA REPUBLIC." A white banner with red, white and blue top said: "ANNIVERSARY OF OUR INDEPENDENCE." A red and blue banner said: "CHUNG HWA REPUBLIC." A white banner bore the inscription:"THE YOUNG CHINA PUBLISHING COMPANY."

White banners lay on the green grass of the square. One of the two brass bands of young Chinese had gold-colored braid on their uniforms; the other had uniforms with black braid. AS the Chinese lads sat on the grass waiting to be photographed their two big drums told who they were. One drum said in English, "NEW CATHAY BOYS," and there were additional Chinese characters in red. The other drum bore the inscription: "YOUNG CHINA MILITARY BAND OF AMERICA."

Yes, OF AMERICA" was there. Many of these young Chinese boys may have been native sons of California.

After the photographs were taken, I followed the procession that passed into Grant avenue under its great outstretching banner announcing, "THE FIRST ANNIVERSARY OF WUCHENG.: The Chinese band had begun to play. Chinese lined the sidewalks, along which I hastened to keep up with the procession in the middle of the street. Chinese women looked from upper windows. San Francisco breezes blew out the gay flags. At the corner of a chop suey noodle factory, the bands turned up the next street. Here they played one selection before the Chinese Six Companies' building, which was decorated with large red lanterns, contrasting oddly with the building's blue front.

The bands turned back. Before dispersing, what was it those young Chinese were playing? Auld Lang Syne. Did it mean that old China was not forgotten - old china across the sea? Or did these Chinese lads merely play it because they liked the melody, or because they had heard the band on some large oriental Pacific liner play it when the great boat moved out from San Francisco?

Yet one more tune was played. It was "America." Yes, these Chinese boys of fourteen or fifteen years of age might celebrate Wucheng, for after all, "America" belonged to them, and they played it as well as a band of trained white boys: