HTML format Copyright © 1998 Louis S. Alfano

All rights reserved.

CHINESE CEMETERIES IN SAN FRANCISCO.

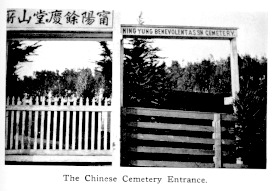

There are two Chinese cemeteries of the native faith in San Francisco, and one small Chinese Christian cemetery. Taking the electric car from the San Francisco ferry building, one rides down into San Mateo County. The conductor stops the car where a large sign at right angles to our road says: "NING YUNG BENEVOLENT ASSOCIATION CEMETERY."

But there is no trace of a cemetery beyond the sign, as one's feet sink in the soft earth of the country road. At the right are willows, and then a fence with a row of tall eucalyptus trees bordering it. At the left are acres of vegetable land with Italians working here and there. Some distance up the road there used to be a stone having Chinese characters at the top, and beneath were the words: "N.Y.B.A.C. ROAD - 20 ft. Wide, 3,898 ft. long."

A cypress hedge begins to parallel the eucalyptus trees. By and by you come to a large gate at the right. Above the gate are black Chinese characters on a white wooden ground, and at one side is an English sign, "NING YUNG BENEVOLENT ASSOCIATION CEMETERY."

How still and pleasant and alone that Ning Yung cemetery seemed, the February day when I first visited it! The grass was green, the sun westering. Away on the hillside stood rows of white boards, each with its Chinese inscription. I walked up the hill and wandered among the Chinese graves. On several were blooming narcissus, the yellow and white Chinese lily; but on two graves were punk-sticks, emblems of Chinese worship. Down the hill, opposite the large gate, was the shrine of the cemetery, a raised cement semi-circle, with a Chinese inscription on the central slab. At either end of the semi-circle rose a large brick kiln, higher than my head. The kilns were covered with cement, and each kiln had a terra-cotta chimney and an iron door. Opening the door, one saw a grate with ashes.

A Shipment of Bodies to the Home Land -

It is a well-known fact that the Chinese generally wish that their bodies may finally rest in the

earth of their fatherland. It is only, however, at periods of a number of years apart that there is a

wholesale removal of bodies to China. Such a removal took place in 1913. Therefore, in March,

1913, when I re-visited the Ning Yung Benevolent Association Cemetery, it was not a deserted

place as at my former visit. I had seen in the newspaper a statement that a new ordinance had

been agreed to by the supervisors of San Mateo County, lowering the fee for the removal of

bodies from the cemeteries from ten dollars to two-and-a-half apiece. "This action," said the

newspaper, "is expected to bring in a large revenue, as the Chinese Six Companies have signified

their intention to remove some eight thousand bodies of their countrymen, and at the former fee,

this work would not have been undertaken."

In the Ning Yung grounds, I saw the activity resulting from the passage of the new ordinance. Afar on the hillside were a number of Chinese. Here and there were new white board boxes, inside each of which was a smaller bright zinc box. The Chinese were sitting on the ground having lunch. An old white man was digging at one spot and a young Italian at another. A pile of narrow white strips of cloth caught my eye. These, the old grave digger thought were for the names of the Chinese, a strip being put into each box. He said that sixteen hundred Chinese were to be removed from Ning Yung.

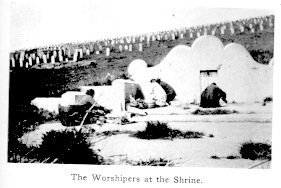

Down the hill, at the center of the shrine, where one or two steps went up to the white slab with its Chinese inscription, some one had been worshiping. In the rectangle of earth, perhaps three feet long by one broad, before the central slab, stood a number of tiny punk-sticks, such as are burned in worship, some having green, some red, some yellow tops. On the edge of the rectangle lay a bunch of matches, and at the left of the rectangle, there stood on the pavement, a little brown jug. on which was a red Chinese paper, with this inscription: "Wine. Lee Wei. Tiensin and Hongkong." It was an offering of wine to the spirit of the dead.

The other and larger Chinese cemetery, that of the Six Companies, lies a mile or so west of Ning Yung, at what is known as "Happy Valley," albeit the cemetery extends over a hillside. When I visited it at the time of the proposed disinterment in March, 1913, the hillside next a road inside the cemetery was covered with purple cabbages. Indigo and purple, they looked up at me as I walked to a nearby shrine. There was a kiln on the right. Far ahead, on and over the hill, were a multitude of Chinese headboards.

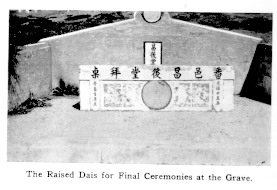

The shrines were scattered over the cemetery, for the convenience of Chinese who wished to make offerings to the spirits of their dead friends and relatives. Before some shrines broken bottles often disfigured the space, as if wine had been offered. A further shrine had bright punk-sticks, as if worship had recently been held there. Some of the headboards atop the hill were blackened, as if they had once been on fire. Before one or two shrines there was a raised dais, on which the coffin could be placed for the final ceremonies before burial.

As I stood at one of the shrines beside the road through the Six Companies' land, a young white man came to me. It seemed that he and another man had been sent here to watch for the Chinese, wh had not yet begun to remove the bodies, but wh might appear at any time. It was the guards' duty to see that no Chinese body was removed without a permit.

Worship at the Tomb Shrines -

I climbed higher on the hill. Here grew blue violets and strawberry vines, and the head-boards

were many. While I wandered, a hack, driven by a white man, entered along the road from the

gateway. It stopped at one of the large shrines next the road. A Chinaman, in American

clothing, and two women and a girl of about seventeen, in Chinese garb, had come in the hack.

A large basket, the size of a Chinese vegetable seller's basket, was taken out of the hack and

placed near the side of the shrine. From the basket came many things for the worship that was

now carried on.

In one corner of the shrine, a small fire had been made, and the Chinese girl lighted numerous little punk-sticks, laid them out, and afterwards carried them across the road to what, the old hack driver told me, was the part of the cemetery set aside for women. He said she had been coming to this cemetery ever since it was established in 1898, and that he had discovered that March, August and October were the months when the Chinese came to worship.

"By next Sunday, there'll probably be fifty hacks here," he said. "This is worship, you know."

Many things came out of the basket of the worshipers before us - oranges, bananas, short lengths of sugar-cane, rice-balls, quantities of punk-sticks, packages of spirit-paper, a fowl, perhaps a duck cooked with its bill turned over its back, and two bottles of liquor, probably wine.

"It's all the best, imported from China," said the hack-driver.

The Chinese man went away on the hillside with some of the punk-sticks for one of the graves, and the observer could tell now how these head-boards upon the hill became so charred and blackened. Probably sometime when the grass was dry, it had been set on fire from the joss-sticks burning on a grave.

The Chinese women carefully attended to the punk-sticks in the rectangle before the center of the shrine. One of them took an armful of the bright-colored paper coverings of the joss-sticks and also, I thought, some of the spirit paper, and both women went to the kiln at the right of the shrine. There, with faces hidden from me by the iron door of the kiln, I could hear the voices, but I could not tell whether they recited prayer while the papers burned, or whether they were merely talking.

Across the road, in the women's plot, I gave the Chinese girl a Gospel in her own language. She opened it, read a few words and put the pamphlet in her pocket. In response to my question, she told me in two of her very few English words, that one grave was her mother's. She had been dead "one year."

At the mother's grave there was considerable "worship," a part of which, I think, was for the spirits of one or two others who were buried in the row of three graves. The hack-driver, who averred to me that he thought it just as sensible as our custom of putting flowers on graves, did not seem to scruple to aid a little in the "worship," for he helped unfasten one package of "spirit paper," and tossed some of them to the wind. Many of them were bright with gold and silver. The wind scattered them about among the cabbages. But some remained to be burned, and with them burned also several pairs of beautifully-colored paper shoes - blue and purple - one pair, with red ornamentation so realistic in appearance, as almost to make one think them of more than paper. These shoes are supposed to be conveyed to the dead through the worship by fire.

The girl and one of the women diligently kept the punk-sticks burning and stirred the pile of spirit-papers. The girl poured wine, or liquor of some sort into a tiny cup, and repeatedly threw the contents upon her mother's grave, and also threw a rice-ball. A fowl was placed before the grave, and some sugar-cane was also offered to the dead. The girl, who was worshiping, put the palms of her hands together, and swung them twice before her, repeating words, probably a prayer. Afterward, when one of the women was worshiping, I noticed that she swung her hands three times in succession.

Worship being almost over, the girl took a wooden receptacle that contained a good many thin strips of wood, probably, bamboo, and crouching, shook the receptacle. As she shook, a number of strips of wood, which were somewhat less than a foot long, fell to the ground. When a number had fallen, she stopped shaking the receptacle, and picking up the bits of wood that had fallen, she looked at the marks on them. The Chinese man, with his pencil and paper, took down the numbers, and the hack-driver told me that they were trying to find out the "lucky numbers" for the lottery.

Afterward, another of the Chinese women shook the receptacle. One of the women also threw what was probably the equivalent of the divining blocks of the joss-house - "good luck" blocks - only they were not big and red, but of a dark color and a different shape, and were a little larger than the black shuttles with which American women make "tatting." The woman threw two of these pieces several times, looking closely at them to see how they fell.

"Worship" being nearly over, the girl began to eat some of the sugar-cane. The convenience of such "worship" is that only the "essence" of the food goes to the next world, the material substance of the food being left to persons yet in the flesh. As the hack-driver ate his portion of sugar-cane, he said that it was sweeter than the American kind.

The Chinese girl went into the cabbage patch and picked several cabbages, stripping off the outer leaves. The cabbages were put into a basket, as it was the food that had been offered in "worship." How ancient the custom of offering food to the dead must be! In Deuteronomy 26:14, we read the words of prayer, "I have not eaten thereof in my mourning...nor given thereof for the dead." One can readily see how the custom of giving food to the dead would arise in a non-Christian land, from the power of human affection, the missing of the loved one at the daily meal, the wish inn some way to send him some favorite article of food, and the fear that he might be hungry in that mysterious world to which he had gone.

"Ning Yung," said the Chinaman to the hack-driver, meaning that they wished to go there next.

One of the women who had been worshiping at a grave, started toward the hack. There was no human being left in that women's plot of the dead for her to speak to, yet on the nearer side of the road, as she partly faced the grave, she said something. Perhaps it was the finishing of a prayer. Moreover, when she reached the farther side of the road, she spoke again, looking back toward the woman's plot, as one might who remembers to say some last word. There had been no tears shed by the Chinese women as they had performed their rites for the dead, yet the sight of the woman turning back to say some last words, before entering the hack, lingered in my memory.

I gathered some of the silver and gold spirit-papers from among the cabbages, and picked up some of the bright red papers that had enclosed punk-sticks and had not been burned in the kiln, but had been left to fly about. One kind of red wrapper had a picture of a god or some flamboyant Chinaman waving a torch above his head. Another yellow wrapper bore the inscription: "Chun Lun Hing, dealer in best quality joss-stick, Macao, China."

With my spirit-papers, I took the road to Ning Yung Cemetery. The hack arrived before me, and stood not far from the Ning Yung shrine. The fowl that had done duty at the woman's grave in the Six Companies' grounds, now stood before the Ning Yung shrine with other offerings. The shrine was deserted, the women having gone to the hill where Chinese bodies were being excavated. A large wagon, loaded with boxes marked for Hong Kong was waiting. Each box contained the bones of some five or six Chinamen, for a number of permits were on the outside of each. The boxes were marked "Ning Yung T. W. Y. Y., Honk Kong, China."

During the latter part of 1913, when the excavations at Ning Yung and Six Companies were over, I consulted the old grave-digger at Ning Yung, who told me that he thought about fourteen hundred bodies had been taken from Ning Yung, and probably more than an equal number from the Six Companies' Cemetery. Doubtless there will not be such a wholesale return of bodies to China again for a long time, since such removals take place only at intervals of about ten years, and possibly the Chinese of the rising generation in California may not be so particular about their bones resting in China.

The Chinese cemeteries in San Francisco were not the only ones from which Chinese bodies were exhumed in 1913, for in November, at the old oriental burying ground at San Jose, in Santa Clara County, there were tiers of boxes containing bones of one hundred and eighty-seven Chinese waiting permission from the State Board of Health at Sacramento for shipment on their last journey to China, where elaborate ceremonies would be performed at the re-burial in the soil of the fatherland. It is said the Chinese have perfect records of deaths and burials for reference. A stone tablet bearing all details is deposited in each coffin at the time of burial. According to the opinion of the State Board, bodies that have been buried more than ten years, are not classed as bodies, but has human "remains."

The Christian Cemetery -

But, thank God, there is another cemetery besides these two for San Francisco's Chinese. For

years Christian work has been done among them and many have died in the faith of our Lord

Jesus Christ. Such would hardly be appropriately buried in a place presided over by a shrine like

that of Ning Yung. There is a Christian cemetery. It lies west of Ning Yung, on the hill

separated from that cemetery by a fence and a cypress hedge. Sections of the hillside belong to

different denominations, and there are low, white signs for the Presbyterian, the Congregational,

the Methodist and the Baptist sections.

On a day when I visited the place, the song of a meadowlark was in the air. Through the dry brakes, I found my way from one old Chinese grave to another, on the lower part of the hill, and I read the inscriptions of Christian faith:

Somehow, I was reminded of the inscriptions of the catacombs at Rome. Out of great tribulation, no doubt, had these Chinese Christians attained to this faith in Christ. From the other side of the cypress-hedge below me, came the voices of those who were excavating Chinese bones. But no one was disturbing with any shovel the resting places of the Chinese Christians. What did it matter whether it was on a California hillside facing the rising sun, or in China itself that these Christians lay asleep for a time, till their Lord should bid them rise?

Sweet rose geranium marked the grave which is Shin Ah Mong's resting place. One could hardly read the inscription for the lichens that beclouded the words on the stone, but they are these that have been the triumphant expression of many a Christian, of many a nationality: Death is swallowed up in victory."

Farther up the hill is a large white stone inscribed "Fong Dock, Salvation Army Soldier." Here was a raised grave with golden California poppies. rose-geranium and other flowers in bloom. The old stone said:

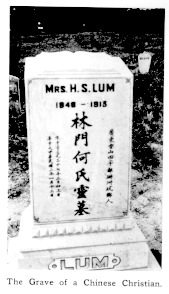

In a recent grave with a large white stone, lay Mrs. H. S. Lum, a Chinese woman of sixty-five years. On top of the stone is an open book made of white marble. On the left-hand leaf of the book is the English inscription: "Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord. Rev 14:13." On the right-hand page are Chinese characters, presumably expressing the same text.

From the higher slope of the hill, one could look down and see away beyond the cypress hedge the distant kiln of the cemetery of Ning Yung, and the top of the shrine where I knew there were on the day of my visit offerings of wine. Standing on that hill in the Christian Chinese cemetery, and beholding the other cemetery below, one felt anew the glorious significance of the Christian hope.

To get in touch with me send e-mail to

Lou Alfano.

Be

sure to include your full name, as I will NOT reply to

unsigned e-mails.

Please do not write from AOL or Compuserve addresses, because these

ISPs BLOCK e-mail from ".it" domains.