St. Elisabeth's

Family Ties

St. Elisabeth's

Family Ties

St. Elisabeth's

Family Ties

St. Elisabeth's

Family Ties

The propagation of dynastic sanctity served to further the political

and spiritual prestige of  dynastic houses.

Political power could be legitimized through the successful propagation

and manipulation of familial ties with recognized saints. For this reason

saints' lives, or vitae, were written in order to promote the sanctity

of ancestors or kinsmen, - women, whose sanctity could thus be used in the

game of political conquest. Such a tradition of dynastic sanctity played

an important role, for instance, in the succession to the Hungarian throne

in the Middle Ages. (See Gábor Lankiczay, "From Sacral Kingship

to Self-Representation: Hungarian and European Royal Saints.") Above:

The Wartburg

dynastic houses.

Political power could be legitimized through the successful propagation

and manipulation of familial ties with recognized saints. For this reason

saints' lives, or vitae, were written in order to promote the sanctity

of ancestors or kinsmen, - women, whose sanctity could thus be used in the

game of political conquest. Such a tradition of dynastic sanctity played

an important role, for instance, in the succession to the Hungarian throne

in the Middle Ages. (See Gábor Lankiczay, "From Sacral Kingship

to Self-Representation: Hungarian and European Royal Saints.") Above:

The Wartburg

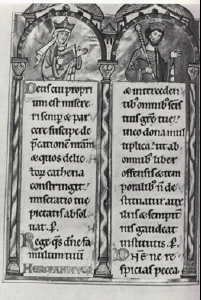

St. Elisabeth's sanctity drew on this tradition, as an Arpadian princess from her father's line she came from the dynasty of Hungarian holy kings. Her mother's line, the Andechs, boasted a total of twenty-one saints and beati between 1150 and 1500. Elisabeth's children drew prestige from their relationship to her. Her son Landgrave Herman II and her daughter, Sophie of Brabant both identified themselves as children of the saint to their political advantage, whereas her daughter, the Praemonstratensian abbess Gertrud (1227-1297) was herself canonized in 1348.

left: Elisabeth's parents Gertrud and Andreas II of Hungary

Elisabeth's vita was appropriated as a means of continuing this tradition through her model. Elisabeth marks a turning point within this dynastic tradition from that of saintly kings, to a new feminine dynastic sanctity based upon the ideals of humility and charity, and identification with the poor. Using Elisabeth's vita as a type of career script, other royal females of her dynasty and region took different aspects of Elisabeth's sanctity as models for their own, reading her life as a script for becoming a saint within the court-culture of their day. Elisabeth is also the first female associated with Franciscan spirituality to be canonized, and as such her model can also be seen as a model for a way in which women, who were much more limited in avenues of spiritual expression, could remain faithful to the spirit of St. Francis.