Return to *North Korean Studies*

What is New about Defectors? (August ~

December 2004)

Digital Choson Ilbo, 9 Dec. 2004

BEIJING -- Professor Zhao Huji, a North Korea specialist at the Central Party School in Beijing, said Thursday that North Korean generals and high-ranking officials are deserting the crisis-plagued state as a mirror of growing instability and its leader's waning authority.

"These high-ranking defectors aren't leaving because of material want, but because these feel chaos within the Kim Jong-il regime... High-ranking administrators like military officials have visited China several times and are well connected there, and because they have money, they have many chances to defect to China," said

Zhao.

North Korea experts calculate that 130 North Korean generals have defected to China, some of whom may have entered the Chinese military, as reported in a recent edition of the International Herald Tribune.

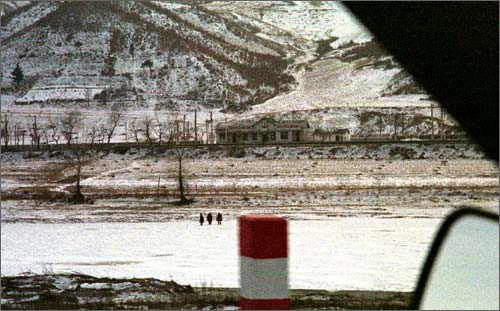

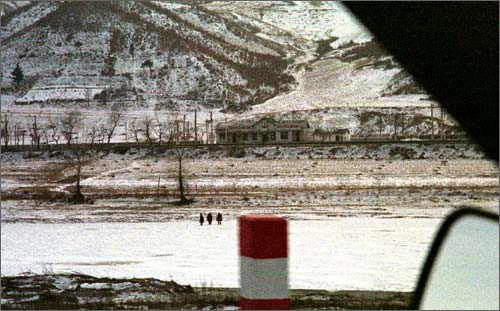

North Korean border guards take a break while out on patrol on the frozen Tumen River.

Behind them can be seen a portrait of Kim Il-sung.

|

However opinion is divided, with other specialists arguing that the removal of Kim Jong-il's portraits from public buildings in Pyongyang and the continuing exodus of defectors does not signify a loosening grip on power by the North Korean leader.

Peking University professor Cui Yingjiu, who studied with Kim Jong-il at Kim Il-sung University and had until recently kept in contact with the North Korean leader, said, "Kim Jong-il has a stronger grip on power than Mao Zedong in China during the 1960s ... In North Korea, there are no people like Liu Shaoqi or Deng Xiaoping [who challenged Mao] to compromise Kim Jong-il's authority."

Cui added that China has less influence over North Korea than is widely believed.

|

by Lee Young-jong, Joong-Ang Daily, December 02, 2004

South Korean intelligence officials said yesterday that a North Korean agent had successfully infiltrated South Korea in the wave of defectors who have fled their communist homeland and sought asylum in the South.

The agent, who recently turned himself in to the South Korean authorities, had been ordered to gather information on Seoul's handling of defectors. According to the sources, the man, who was not identified, returned to North Korea to deliver information to authorities in

Pyeongyang.

It is the first time Seoul officials have acknowledged that a North Korean spy posing as an asylum-seeker has reached the South. The government and the National Security Council were told about the case by intelligence officials four months ago, but the information has been closely guarded.

A 28-year-old pretending to be a defector asked for asylum at the South Korean Embassy in Beijing in November 2002, an intelligence official, who asked to remain unidentified, told the JoongAng

Ilbo.

According to the sources, the alleged spy was affiliated with the security agency of the North Korean People's Army. After successfully passing screening procedures by embassy staff to verify that he was a bona fide refugee, the agent was sent on to South Korea by way of a Southeast Asian country in January last year.

During a 15-month stay in South Korea, an intelligence official said, the agent gathered information related to the location of safe houses for defectors and their security status. He also collected information on the South Korean military's Defense Intelligence Command.

The North Korean agent obtained a South Korean passport in April and left for China in April, the official said. He then returned to North Korea to deliver a written report. Until early May, he attended an espionage training session in

Sinuiju, near the Chinese border, and was instructed to return to South Korea on a new mission, the South Korean intelligence official said.

The spy reached the South on May 19, and then in early June decided to turn himself in to the South Korean authorities.

According to interrogators who had questioned the agent, he used to be a sergeant of a border patrol unit in North Hamgyeong province in 1997. He then crossed the border to seek a better life in China, but was arrested and repatriated to the North during a crackdown. After repatriation, North Korea forced him to work as a spy, he told South Korean investigators.

Translated from Korean by Hamel, Marmot's Hole, 3 Dec. 2004

It has been revealed that a member of a North Korean military intelligence

security organisation passed himself off as a North Korean defector and came to

South Korea, where he spent 1 year and 3 months secretly working as a spy within

the country.

Asking for anonymity, a source inside the central government said on the 1st

December “In July this year authorities referred a man identified as a Mr Lee

(28), who entered South Korea as a defector through China in January last year,

to the Prosecutor without detention on suspicion of having broken the National

Security Law, when after initial investigations the suspicion arose that he was

a spy.” This is the first case of a North Korean defector (탈북자/talbukja

) coming south, gaining South Korean citizenship and engaging in espionage.

According to authorities, Mr Lee was an agent belonging to the 11th Defence

Command/Headquarters of the North Korean army who entered the consulate of the

South Korean Embassy in Beijing with other defectors in November 2002 demanding

passage to South Korea.

Two months later Lee came to the ROK via a south-east Asian country and

proceeded to gather information about the talbukja interrogation center

‘Daeseongkongsa(’대성공사)’. [More on

this ‘대성공사’ place some other time. It needs to

be covered but I haven’t the time, energy or resources to do it today -

Hamel.] Daeseongkongsa is run by the ROK Army Intelligence HQ. He also

gathered information on the location and security facilities of ‘Hanawon‘,

the talbukja resettlement facility, which has the highest level of

security amongst national security installations, ‘ga‘.

Last April, saying that he was going to going to meet his North Korean

family, Lee was issued a passport and left the country, crossing the border from

China into North Korea. There he reported the secrets he had learned in South

Korea in a document to the North Korean army’s border protection main

office’s director for the North Korean State Security agency (the bowibu/보위부).

South Korean authorities are currently investigating this.

Furthermore, from late April until early May he reported his intelligence at

some sort of place in South Pyongan-do where agents to be sent to South Korea

are trained.

After this, from the 7th May for 10 days Lee received secret training in

spying on South Korea at a guest house (chodaeso/초대소)

in Sinuiju City, North Pyongan Province, and was given an agent’s code name

(127) and a pre-arranged noise/sound/call for secret communications. North

Korean authorities ordered Lee to return to South Korea and infiltrate the

Association of North Korean Defectors [the

탈북자동지회, run by ex Korean Workers Party

and prominent defector Hwang Jang-yop - Hamel] and other unification related

groups and, after being active for a time, to bring membership cards and other

pieces of evidence back to North Korea.

Authorities say that after arriving at Incheon port on may 19th via China,

Lee sent the message “I have arrived safely” to North Korean agents in

China.

Lee is originally from Deokseong County, South Hamgyong Province, and worked

as a sergeant in a border patrol unit in Onseong Country, North Hamgyong

Province, before fleeing North Korea and crossing the border into China in June

1997 [the Korean original uses the verb 탈북하다 meaning

to flee or escape from North Korea - Hamel] where he was caught by Chinese

security police and forcibly repatriated to North Korea. The North Korean

authorities threatened him with execution and forced him to swear an oath of

loyalty and then gave him some Renminbi [the Chinese currency] as operational

funds, ordering him “Go and ferret out the state of anti-DPRK activities and

anti-Kim Jong Il conspiracies by South Korean-related organisations in China.”

Accordingly, from February till November 2002, Lee watched the movements of talbukja

in China and reported them. Then he received new orders to enter South Korea as

a spy and entered the consular section of the ROK embassy in China and “fake

defected.” In a telephone call with a journalist on the night of the 1st of

December, Lee said “I have neither engaged in spying activities nor turned

myself in.” However, he did say “It is true that I have been under

investigation by the security department of the Prosecutor’s office, but

nothing concrete has been alleged,” and hung up the phone. This is the first

time since the June 15th Joint Declaration by North and South Korea that a case

of a North Korean agent directly inserted into South Korean society by the North

Korean authorities for the purposes of spying has occurred.

The government and the National Safety Council received reports from the

authorities concerned of the arrest of a talbukja spy over four months

ago, but have not made the case public, rather concealing it.

Reuters, Monday, November 8, 2004

SEOUL (Reuters) - Three former North Korean inmates gave harrowing accounts on Monday of alleged suffering at political camps, part of an event organized by activists aimed at prodding Seoul to tackle Pyongyang on human rights.

|

|

The reclusive communist state usually gives a prickly response to criticism of the way it treats its citizens. South Korea has largely avoided confronting it on the issue for fear of hampering reconciliation efforts.

"North Korean prisons aren't just prisons," ex-prisoner Kang Cheol-hwan told a forum taking place in the lobby of the National Assembly.

"The situation is similar to Auschwitz, back then people were killed by gas. In the North, people are worked to death without being fed. Only the method is different."

|

Kang said prisoners were fed only corn, salt and porridge, despite having to work from around 4 a.m. to 8 or 9 at night, with just a brief break.

"The way to bring about change is by confronting its rights issues," he said, urging the South Korean government to stop turning a blind eye to the matter.

Two other former inmates, who said they had been held in a prison in Hamkyung province, also re-lived their past at the event entitled "North Korea Holocaust."

It was organized by the International Coalition for North Korean Human Rights, a South Korean rights group.

Some mothers resorted to feeding their children baby rats, recalled Kim Young-soon, adding this was driven by folk tales that this could get rid of bulging stomachs caused by starvation.

Former detainee An Hyuck said there were at least five such camps and 150,000 inmates.

"We were surrounded by death every day," he said, adding that anyone trying to escape would be shot.

A report by the U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea has said the North has between 150,000 to 200,000 political prisoners working as slave

laborers. The North consistently denies these camps exist, although British Foreign Office minister Bill

Rammell, who visited the Pyongyang in September, said North Korean ministers told him about running prison camps for "re-education."

While North Korea has engaged in dialogue with some European countries on human rights, it has refused to discuss the issue with South Korea or the United States.

The North, which is under international pressure to scrap its nuclear weapons programs, said a new U.S. law urging more human rights in the North meant nuclear talks were meaningless because America was "hell-bent" on topping the communist state.

The North Korean Human Rights Act, adopted last month, calls for the expansion of human rights for the North's 22 million citizens, and earmarked up to $24 million a year for the effort.

N.Korean

Defector in Vladivostok Tests the North Korean Human Rights Act

SEOUL Ten days after President George W. Bush signed into law a bill easing the way for North Koreans to win political asylum in the United States, a

North Korean man jumped onto the roof of the American consulate in Vladivostok, Russia, late last month, entered the building and asked for

asylum. "He's still here," a U.S. consular official said in a telephone interview.

Saying that privacy rules ban divulging further details, the official added: "We are working the case. There is not a resolution."

Holed up in the consulate on Pushkin Street, a building with a sweeping view of Golden Horn Bay and the Sea of Japan, the defector, a construction

worker in his 40s, presents the first test of the North Korean Human Rights Act.

Passed unanimously by both houses of Congress in September, the bill was signed by Bush on Oct. 18.

In addition to removing barriers to granting U.S. asylum to North Korean refugees, the law calls for expanding American radio broadcasting into

North Korea to 12 hours a day, sending radios into North Korea, granting $2

million a year to groups supporting human rights, democracy and a market economy

there, and spending $20 million to help settle North Korean refugees.

By mid-February, the State Department is to submit to Congress guidelines for accommodating North Korea

asylum seekers who present themselves at U.S. consulates and embassies. North Korea has bitterly attacked the law, to the point of telling

The Wall Street Journal last week that it will not participate in regional talks

over its nuclear weapons program until the United States repeals the law.

In

the latest tirade, Minju Chosun, an official publication, said Tuesday that

the U.S. "is trying to send in obscene publications and discrepant rogue recordings using

travelers, and worse, mini-radios and televisions using

balloons."

The majority of North Korean refugees go into China, where thousands live a hunted existence. But Russia's Far East could also become a new magnet for

people fleeing North Korea, widely considered one of the world's most repressive nations.

Douglas Shin, a Korean-American pastor working with North Korean refugees, predicted in an interview here Sunday that the Russian Far East could

become a new escape route for North Koreans, to South Korea or to the United States.

"If the U.S. accepts him, this will be the harbinger of more cases to come," he said of the defector.

Russia and North Korea share only a 10-mile land border, but North Korea freighters routinely stop at nearby Russian ports and a direct rail line

brings an estimated 4,000 North Koreans a year to work in construction and logging, all under tightly supervised construction contracts.

"My country is like a big prison," a North Korean translator said by

cellphone Friday from the Vladivostok apartment of Russians who were hiding him until

he can win asylum in South Korea or the United States. "I absolutely hate the political system in my country and I see no future there."

Asking not to be identified by name, he said he escaped detention in a

North Korean dormitory in Vladivostok by jumping out a second-story window, breaking

bones in his feet. Speaking fluent Russian that he honed at a foreign language institute in Pyongyang, he said he lost his girlfriend in college when

security agents dragged her out of a class and sent her into rural exile with her family. Her father, a prominent economist, was purged for

advocating free-market experiments.

"My country is hell, and many people want to leave, but nobody will talk

about it," he said, attributing this silence to the pervasiveness of informants.

Fearful of being caught by the Russian police and repatriated to North

Korea, he begged over the phone: "Please, please help me. I will go to any country

that would offer me political asylum."

In China, consulates, embassies and foreign schools increasingly look like

armed camps because of repeated invasions by North Koreans seeking asylum. Currently, about 130 North Koreans are camped inside the South Korean

embassy in Beijing. Embarrassed by these break-ins, the Chinese police raided two

safe houses last week and arrested 62 North Koreans and two South Korean organizers.

But in a measure of how the plight of North Korean refugees has become a

cause on American college campuses this fall, Liberation in North Korea, a new student group, picketed the Chinese mission to the United Nations in

New York last Monday, waving signs reading "Free the North Korean Refugees" and "Don't

Send Them Back!"

The six-month-old group has chapters in 70 U.S. colleges and cities.

Emulating the 1970s movement that won the right to emigrate for millions of Soviet

Jews, the group is to open an office in New York on Monday.

FATE OF 29 REFUGEES WHO RUSHED JAPANESE SCHOOL IN CHINA

UNDECIDED

Agence France-Presse reported that the fate of 29 refugees who rushed a Japanese school in Beijing hung in the balance as Japanese

consular officials interviewed them to find out who they were and what they wanted. "We are still trying to find out who they are," Japanese embassy

spokesman Keiji Ide told AFP. "They claimed they are North Koreans but we should be careful." The 11 men, 15 women and three children were "more

relaxed" after sleeping in the Japanese embassy Wednesday night, he said. Ide said that as far he knew the refugees had not been in contact with ROK

or PRC officials. A senior foreign ministry official in Seoul said the group would be accepted if they wanted to come to the ROK while Japanese

Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi pledged that they would be treated "in a humanitarian way".

("FATE OF 29 REFUGEES WHO RUSHED JAPANESE SCHOOL IN CHINA UNDECIDED", 2004-09-02)

by Leonid A. Petrov, Radio Australia (Chinese Service), 3

September 2004.

近日,二十九名朝鲜人闯进北京的一所日本人学校寻求庇护。这二十九名朝鲜人中包括十一名男子、十五名妇女和三名儿童。日本首相小泉纯一郎以及日本驻中国大使馆都已经表示,日本会按照人道主义原则来处理该事件。中国仍未就这群人的身份作出说明,中国官方发言人表示,中国警方正就此进行调查,其中也包括对他们的身份进行核实。澳大利亚国立大学亚太研究所朝鲜问题专家列昂尼德·佩特罗夫

博士 (Dr. Leonid Petrov)

认为这二十九名朝鲜人很有可能会经由第三国前往韩国,虽然朝鲜肯定会表示不满,但这不会影响其参加第四轮六方会谈。请听澳广中文部记者余伟文的报道。。。 (in

Chinese)

ABC Radio, Asia-Pacific

Presenter/Interviewer: Claudette Werden Speakers: Hae Nam Ji, North Korean

defector; Douglas Shin, US-based human rights activist, Professor Kenneth Wells,

the Australian National University

Concerns over trafficking and asylum claims North Korea has recalled its

ambassador to an unidentified Southeast Asian country to protest against its

role in the secret airlift in July of more than 460 North Korea refugees to the

South. Human rights workers say refugees often slip into China then travel

overland to Southeast Asian countries, from where they hope to reach South

Korea. There's growing speculation the US North Korean Human Rights Act, which

earmarks hundreds of millions of dollars for North Korean refugees will lead to

a giant influx of asylum seekers into Indo-China...

By Jeremy Kirk

Far Eastern Economic Review WEB SPECIAL / September 01, 2004

One cold night in 1965, Sgt. Charles Robert Jenkins disappeared from a patrol in South Korea. Forty years later he has resurfaced. In his first interview since leaving North Korea, he tells the Review his story

After surviving for nearly four decades in North Korea and spending a month in a Tokyo hospital room, United States Army Sgt. Charles Robert Jenkins wants closure. And to get it, he’s ready to tell his story.

In Jenkins’ first interview since taking flight from the North Korean regime in July, the alleged defector tells the REVIEW why he intends to turn himself over to the U.S. Army even though he expects to face a court martial. Jenkins reveals how he sought asylum at the Soviet embassy in 1966, endured repeated beatings at the hands of another American defector, and was pressured by North Korean authorities to reject a personal invitation by the Japanese prime minister to leave the country with him. And he describes how his difficult life in North Korea was lifted from misery by a love affair with a Japanese nurse who shared his hatred of the communist regime and eventually helped him and their two daughters escape.

“When I got on the airplane in Indonesia coming to Japan,” Jenkins says, speaking in a colloquial English that reflects his seventh-grade North Carolina education and decades spent in a foreign land, “my intentions was to turn myself in to the military for the simple reason I would like to put my daughters with their mother, one thing. Another thing: I’d like to clear my conscience.”

Rising from his hospital bed at the Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Jenkins greets his visitor with a deferential Korea handshake, briefly makes eye contact and immediately looks away. A graying 64-year-old with a heavily creased face, Jenkins is still restricted in what he says: under the advice of his military lawyer he withholds the circumstances of his alleged desertion to North Korea and many of the details of his life there-information that he intends to offer to the Americans in return for their leniency.

On September 1, Jenkins announced to the press that he would report to U.S. Army Camp

Zama, near Tokyo, and "voluntarily face voluntarily the charges that have been filed against me by the U.S. Army." The U.S. charges Jenkins with desertion, aiding the enemy, soliciting others to desert and encouraging disloyalty. In a document seen by the REVIEW that was

initially intended to argue his case for an other-than-honourable discharge, Jenkins acknowledges that he is guilty of at least one of the four charges against him or of a lesser included

offense, without specifying precisely which offense. The U.S. military informally rejected Jenkins’ discharge request.

The U.S., not wishing to send the wrong message to its troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, has publicly vowed to prosecute Jenkins. But privately the matter is much more delicate. Jenkins presents a starkly different picture than of a deserter who enjoyed living in North Korea and supported the regime by acting in propaganda movies. It’s of a man-and family-who scraped by while North Korean officials watched their every move.

As he talks, Jenkins stares at the floor, absorbed in his solemn past. Frequently on the verge of tears, his voice cracks and wavers when he speaks of his wife and children. A three-pack a day smoker who suffers heart problems and anxiety attacks, Jenkins speaks slowly, in a hoarse North Carolina drawl, deliberately choosing each word as he lucidly recalls dates and events from decades ago.

Jenkins arrived in North Korea already a service veteran. He dropped out of school in North Carolina in the seventh grade, not long after the death of his father, and in 1955, at 15, he entered the National Guard. After an honourable discharge in April 1958, he enlisted in the regular Army. By August 1960 he had begun a 13-month tour in South Korea, during which he was promoted to sergeant; he was returned for a second tour in September, 1964. Then, on a bone-chilling night early the following January, on patrol along the Demilitarized Zone, the 24-year-old sergeant with an unblemished nine-year service record vanished. The U.S. government considers him a deserter, saying that he left behind letters stating his intention to defect; members of his family in the U.S. have said they are convinced that he was captured by the communist state.

From 1965 to 1972, on the other side of the DMZ, Jenkins shared a harsh life with three other alleged U.S. Army defectors:

Pfc. James Joseph Dresnok, Pvt. Larry Allen Abshier and Cpl. Jerry Wayne Parrish. “At first the four of us lived in one house, one room, very small, no beds-we had to sleep on the floor,” Jenkins says. “There was no running water. We had to carry water approximately 200 metres up the hill. And the water was river water.”

The North Koreans played the Americans against each other, Jenkins says. “If I didn’t listen to the North Korean government, they would tie me up, call Dresnok in to beat me. Dresnok really enjoyed it.”

The diminutive Jenkins, about 1.65 metres tall, describes Dresnok as “a beater, 196 cm tall, weighed 128 kilograms. He’s big. He likes to beat someone. And because I was a sergeant he took it out on me. I had no other trouble with no one as far as Abshier and Parrish, but

Dresnok, yes.”

Abshier died of a heart attack in 1983 and Parrish died of a massive internal infection in 1997, according to Jenkins’ discharge request. Dresnok is still living in North Korea.

An August 25 psychiatric report by Tokyo doctors, seen by the REVIEW, says Jenkins suffers from a panic disorder as a result of his treatment. “He had been suspected for espionage and continuously censored. During the first several years, he was forced to live together with three American refugees so as to mutually criticize their capitalistic ideology with physical punishment such as beating on face,” the report says.

Jenkins would have had particular trouble erasing his past: He bears a tattoo of crossed rifles-the branch insignia of the infantry-on his left forearm. When he got the tattoo as a teenager in the National Guard, the letters “U.S.” were inscribed underneath; the North Koreans cut the letters away.

According to Jenkins’ discharge request, which was written on his behalf by his military attorney, Capt. James D. Culp, Jenkins and the three other men tried to escape. “In 1966, Sgt. Jenkins even risked his life to leave North Korea by going to the Russian embassy and requesting asylum. Obviously, the Russian government denied the request.”

During the 1960s, according to another revealing passage in the discharge request, Culp writes that contrary to rumours, “Sgt. Jenkins had no interaction of any kind with any American sailor taken captive during the USS Pueblo incident.” The January 1968 incident began when the North Koreans seized a U.S. Navy spy ship off the country’s coast near

Wonsan. One crew member was killed, while 82 others were beaten and threatened with death before being released 11 months later, after an embarrassing apology by the U.S..

Meanwhile, between 1965 and 1980, Jenkins says he was beaten by Dresnok at least 30 times. Then, in 1980, Jenkins met Hitomi Soga, and his life changed. “Approximately 10 o’clock at night she came to my house,” he says in the interview. “At that time she was 21 years old. I was 40 years old. Anyway she came to my house, the Korean government told me for me to teach her English so they told me to take a few days rest so that we could get very well acquainted, so after about 15 days I started teaching her English.”

Soga had been abducted in 1978 by North Korean agents in Japan, and brought to North Korea. “They wanted a schoolteacher to teach the Korean children Japanese language, Japanese customs in order to turn them into espionage agents,” says Jenkins. But the kidnappers made a mistake, he says. “The North Korean government did not have any use for my wife because she was not a school teacher, she was a nurse. Therefore they had nowhere really to put her, so if she’s with me they’d know where she’s at.”

When Soga told Jenkins one week after they met that she had been kidnapped, Jenkins says he couldn’t believe it. “I’d been in North Korea at that time approximately 15 years and I never heard of anyone being kidnapped. I never heard anything about any civilian being taken to North Korea by force. I learned that my wife-she didn’t like the Koreans for it. I also learned that when my wife was taken, the same night her mother disappeared. Her mother never been heard from again. I felt very, very sorry for her. And she learned that I had been in North Korea for 15 years. She knew that I also did not want to be in North Korea so me and her became much closer than before. So it wasn’t long after that I asked her to marry me. She said she must think about it a little bit. Her and I got much, much closer and in the end she said she would marry me. So I notified the Korean government, and they agreed. They didn’t care.”

Jenkins says “there was no one in the village I lived in that thought that she would ever marry me” because of their age difference. “But after meeting her 38 days later we were married. My wife and I became very close as far as love because she hated the (North) Korean government as well as I, so her and I joined hands in marriage on August 8, 1980. From that time on we lived very, very happy.”

The couple’s first daughter was born three years later. “I named her Roberta because my name is Robert. My wife I told her to give her a second name. She gave her the name Mika and of course my name is Jenkins. Mika means in Japanese ‘beautiful.’”

Their second daughter was born in 1985: “We named her Brinda Carol Jenkins. That’s B-R-I-N-D-A. The reason, my half sister in America was named Brinda Carol.”

While Jenkins was building a family, to the outside world his existence and that of other Americans in North Korea was slipping into legend. Jenkins appeared in a North Korean

anti-U.S. propaganda film in the 1980s, but by the 1990s the notion that there were still Americans living in Pyongyang was mostly a rumour. It was not until Jenkins resurfaced in 2002 with his teenage daughters that his presence was confirmed.

That year, in a summit with Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, North Korean Leader Kim Jong Il agreed to allow a number of Japanese who had been abducted by North Korea to return home. The issue of abductees had long been an emotional issue for the Japanese public and a major sticking point in relations between the two countries.

Jenkins’ wife Hitomi went back to Japan that October, leaving her husband and their two daughters behind and bringing international attention to the family. Soga soon became a national hero in Japan, trailed by the media. And Jenkins showed his face as well, giving a rare interview to a Japanese magazine in North Korea. He was quoted as saying that he had not known until that year that Soga was an

abductee; he was also quoted as praising Kim Jong Il.

Now that he’s left the country, Jenkins no longer disguises his bitterness at the North Korean regime. His legal defence is based in part on the notion that he learned to feign fealty to a regime he despised to avoid death and keep his family together.

Following Soga’s release, the North Korean government sought to convince her to return to her husband and daughters, while others tried to find a way to reunite the family in another country. In May 2004, Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi traveled to North Korea a second time. On this visit he won the release of the children of Japanese

abductees, and tried personally to persuade Jenkins to come to Japan.

Jenkins says he was told he had 10 minutes with Koizumi, but the meeting lasted nearly an hour. “At that time, my wife had been in Japan for 21 months,” he says. “Prime Minister Koizumi had a document signed by Kim Jong Il. He got it that morning.” The document said that Jenkins and his daughters could leave with Koizumi.

“But before Prime Minster Koizumi came that day,” says Jenkins, “four people came and talked with me what would happen to me if I left North Korea. One was the vice-minister for foreign affairs. The other three I don’t know exactly who they were. They come and give me a lecture on not to go to Japan. And I knew if I left that day I would never get to the airport.”

Jenkins says he also knew the room he was in with Koizumi and his delegation was bugged. “So I told Prime Minister Koizumi I could not leave North Korea,” Jenkins says. “He said, ‘North Korea will not let

[Hitomi] leave if she comes back and she does not wish to come back to North Korea.’ He said ‘Today I would like to take you and your daughters with me to Japan.’”

Jenkins suggests that he feared what would happen if he accepted the invitation. “I knew that if I left the guest house that we met Prime Minister Koizumi in, instead of going right to the airport they’d had went to the left and I would have went right back to the area I lived in before and it may have been the end of my life,” Jenkins says, his voice cracking.

Jenkins says he was told later that day that Kim Jong Il was very pleased that he did not go to Japan with his daughters. The North Koreans then told Jenkins they would allow him to travel to a third country to meet his wife and bring her back to North Korea.

“North Korea said, ‘let’s go to China.’ I agreed,” says Jenkins. “But my wife would not. She said no.” Soga, determined not to return, feared that China was too close to North Korea. Instead, a meeting was arranged for July in Jakarta.

“The reason I agreed to go to Indonesia because at one time it was a socialist country for one year-that was under Sukarno,” says Jenkins. “The purpose of going to Indonesia was to bring my wife back to North Korea. And they (North Korean officials) thought if I went with my two daughters, that she would follow me. But she would not do so and I had no intentions of going back to North Korea.”

That leaves Jenkins to face his next challenge: a possible court martial. His military lawyer, Capt. Culp, says Jenkins can offer the U.S. details about the use of foreign nationals in the North Korean spy programme. The request for a discharge asserts that Jenkins can confirm that “a number of Americans were used, most often unwillingly, by North Korea to arm spies with English-speaking skills so they could target American interests in South Korea and beyond.”

Culp writes, “The value of this intelligence about the lives and fates of the fellow Americans who lived for decades in North Korea is immeasurable.”

The document suggests that Jenkins can help American intelligence identify possible North Korean spies: “At least three other Americans who are suspected of deserting to North Korea were allowed to marry East European and/or Middle Eastern women who had been brought to and held in North Korea against their will. In two of the cases, the Americans had multiple children who are now young adults who appear to be American or European themselves.” Jenkins possesses what he says is an April 2004 photograph, seen by the REVIEW, of an ageing

Pfc. Dresnok with 19-year-old Brinda and five other non-Korean looking people.

Jenkins has been at the Tokyo hospital since arriving in Japan. In addition to his chronic health problems, he is recovering from prostate surgery in April in North Korea that left him with an infected post-operative wound. Koizumi, a supporter of Washington in the war in Iraq, has raised Jenkins’ case with President George W. Bush, but U.S. officials insist that the two governments have not negotiated over the outcome of the ongoing legal process. Jenkins expresses appreciation to the Japanese government, who made his wife’s freedom possible, and eventually took in him and his daughters. “It was not my intention whatsoever for the Japanese government to try to get me out of trouble,” Jenkins says. “And I really appreciate the Japanese government for all they have done for me.”

What he wants now is an end to a nearly four-decade Odyssey, as he prepares to turn himself over to the Americans. He has no interest in getting a civilian attorney. “The American Army has supplied, assigned a very capable man to me, to help me, bring me to military justice. I don’t think I need no civilians. All I want to do is clear myself with the American Army.”

The Washington Post, August 29, 2004

by Roberta Cohen, Senior Fellow and Co-Director, The Brookings-SAIS Project on Internal Displacement

Whatever would Ronald Reagan think of the six-party talks to get North Korea to dismantle its nuclear weapons program? Although Kim Jong Il's Communist government is the world's worst human rights violator, the United States, Japan and South Korea have managed to exclude all reference to humanitarian and human rights concerns from the discussions. Their fear is that any mention of the 200,000 political prisoners in forced labor camps, the suppression of the population's civil and political freedoms or the punishment meted out to those who try to flee the country would antagonize the North Korean government and jeopardize chances for a nuclear agreement.

This is hard to understand, given that when confronted by the Soviet Union, which had far greater nuclear power and targeted it specifically against the United States, Reagan did not see fit to give up on human rights goals. In fact, he publicly affirmed in 1982 that "the persecution of people" must be "on the negotiating table or the United States does not belong at that table." Similarly, President Jimmy Carter before him negotiated the SALT II arms control agreement with the Soviets while calling attention to human rights concerns.

Reagan and Carter were able to make this link because of the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, an East-West agreement that created a multilateral forum for discussing security concerns, economic and scientific issues, and human rights. Moscow signed on for security guarantees -- the acknowledgment of post-World War II borders -- while the West secured a commitment to advance human rights. In fact, one of the lessons of this period was that only in that broad context of strategic, political and economic issues could progress be made on human rights.

Once they resume, the talks with North Korea, which involve the United States, South Korea, Japan, Russia and China, could create a multilateral forum for the Korean Peninsula along the lines of the Helsinki process. The talks already cover nuclear and security issues, and more recently economic questions were added. Human rights and humanitarian issues should be brought in as well. For one thing, foreign investment in a country with forced labor must be linked to human rights standards. Any increase in food aid should go hand in hand with humanitarian principles of unimpeded access and equitable distribution. Nuclear verification and inspections would benefit as well from these openings.

South Korea's support should be sought as a first step toward creating a Helsinki framework. Since 1994 South Korea has gained experience of the Helsinki process through its partnership with the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the successor to Helsinki. On the European continent, South Korea promotes democracy and human rights and sends election monitors to the Balkans. But on the Korean Peninsula it looks the other way, fearing that any mention of human rights in the North would trigger turmoil, collapse and an outpouring of refugees.

Yet, since 2001, North Korea has been involved, albeit modestly, in "human rights dialogues" with the European Union and the ambassadors from Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom. In a note to the United Nations, the North Koreans claim to have allowed the European Union "access to

reform-through-labor centers and contact with former inmates."

Using those talks as a springboard, Europe's Helsinki organization could offer to bring North Korea into observer status. This would expose the country to multilateral discussions about democracy, freedom of movement, family reunification and the safeguarding of civil and political freedoms. Within this broader political and security framework, North Korea might be more willing to face up to its international human rights obligations.

China will need to be brought into the process as well. It hosts the six-party talks and is North Korea's primary ally. Between 200,000 and 300,000 North Koreans have fled to China because of famine, lack of work and persecution. There they face the threat of arrest and deportation. Yet promoting fairer food distribution in North Korea and improved human rights conditions would help curb refugee flows into China. A regional forum could also explore burden-sharing with countries willing to resettle North Koreans, such as Russia, where a provincial government has said it would take 200,000, and the United States, where Congress has expressed readiness to accept North Korean refugees.

Finally, a multilateral framework would help reconcile the differences between humanitarian and human rights advocates over how to deal with North Korea. Relief workers delivering food aid to North Korea fear that any overt criticism of the North's human rights record would limit humanitarian access. But mounting concerns over the diversion of international food aid to the army and communist elite -- rather than to the 6.5 million Koreans reported at risk -- have led to the withdrawal of leading nongovernmental organizations and a reduction in donations from governments. A Helsinki process would make food distribution part of the discussion along with human rights issues. As matters stand, a sense of direction is lacking for dealing with the serious human rights and humanitarian problems on the Korean Peninsula. The Helsinki process provided that essential element for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the 1970s and 1980s. Adapted to Asia, it could do the same for North Korea.

NORTH SEIZED DEFECTOR ON HONEYMOON

Joongang Ilbo reported that a DPRK defector on her honeymoon in the PRC has been kidnapped and returned to her former homeland, a human rights activist

group in Seoul has claimed. The ROK's Foreign Ministry said yesterday it has asked PRC authorities to investigate the report. Jin

Myong-suk, 24-year-old woman, whose last name is Jin, and her husband were attacked on

Aug. 8 near the PRC's border with the DPRK by a group of men speaking DPRK dialects, said Doh

Hee-yoon, secretary-general of the civic group, Coalition for Human Rights of Abductees and North Korean Refugees. Seoul's

Foreign Ministry said yesterday that it learned about the apparent seizure immediately after it took place because the couple's relatives filed

reports. The ministry said it asked Beijing to look into the incident, but has so far received no information about it.

("ACTIVIST SAYS NORTH SEIZED DEFECTOR ON HONEYMOON", 2004-08-26)

REGIME BLASTS S. KOREA FOR ACCEPTING DEFECTORS

Los Angeles Times reported that the DPRK denounced ROK authorities as "wicked terrorists" for orchestrating an airlift of 468 DPRK defectors and said the

move was part of a plot to bring down the communist regime. Commenting on last month's operation to bring the refugees to the ROK from Vietnam, the

DPRK's official news agency said the defectors had been abducted and should be returned to the

DPRK. Seoul says the airlift was a humanitarian

gesture. ("REGIME BLASTS S. KOREA FOR ACCEPTING DEFECTORS", 2004-08-23)

N. KOREAN PROTESTS CAUSE TROUBLE FOR S. KOREAN-VIETNAMESE TIES

Chosun Ilbo reported that it was learned Sunday that there were serious diplomatic aftermaths following the airlift of 468 DPRK defectors

to the ROK from Vietnam. According to Uri Party lawmakers who visited Vietnam from August 15-20, as local media widely reported on the mass

entrance into the ROK of the defectors, the Vietnamese government, which had permitted the defectors to go to the

ROK, received strong protests from

the DPRK government and was placed in a very awkward situation. They said the Vietnamese authorities' mistrust of the ROK government has grown. Rep

Im Jong-seok, who was a member of the team, said the DPRK severely protested to the Vietnamese government, and the Vietnamese are extremely

embarrassed and in a situation they cannot endure. He also said that because of this incident, the escape route for defectors has been

completely shut off, and the Vietnamese government can no longer help with defectors.

("N. KOREAN PROTESTS CAUSE TROUBLE FOR S. KOREAN-VIETNAMESE TIES ", 2004-08-23)

REPORT: JENKINS READY TO DISCUSS PLEA DEAL

The Associated Press reported that alleged US Army deserter Charles Jenkins - accused of defecting to the DPRK in 1965 and currently in Japan - is ready

to meet American military officials to discuss a plea bargain, a media report said Friday, citing unidentified government sources. Jenkins

indicated to Japanese government officials that he intended to seek a plea bargain following talks with an independent legal counsel from the Army

this month, Kyodo News agency reported. Jenkins plans to go voluntarily to Camp

Zama, an Army base just outside Tokyo, where he is expected to plead

guilty to some of those charges in return for a lighter sentence, Kyodo said. "The U.S. military will indicate its course of action within the

month," Kyodo quoted a Japanese government source as saying. ("REPORT: JENKINS READY TO DISCUSS PLEA DEAL",

2004-08-21)

NORTH TELLS DEFECTORS THEY CAN COME HOME

Joongang Ilbo reported that the DPRK has issued an appeal to its citizens who have defected to the ROK to return home, promising there would be no

reprisals if they choose to come back. The Central Committee of the Democratic Front for the Reunification of the Fatherland, the DPRK's organ

handling ROK affairs, released the appeal through Radio Pyongyang over the last two days. The state-controlled broadcast is for listeners outside the

DPRK. ROK officials said they could not recall the DPRK previously ever making such an appeal. The message, titled "a letter to brothers kidnapped

to South Korea" was aired Wednesday and yesterday. The DPRK encouraged all and any defectors to return home. "You can return in a group or

individually to your republic," the broadcast said. "We will receive you with a warm welcome."

("NORTH TELLS DEFECTORS THEY CAN COME HOME ", 2004-08-20)

Two British filmmakers have remarkably been given exclusive permission to tell the full story of

one of the Cold War's last remaining mysteries. (NK Zone)

Nicholas Bonner, head of Koryo tours and documentary filmaker, informs NKzone that he and British Filmaker Daniel Gordon will begin work in North Korea in September on a new film about the four U.S. servicemen who defected to the DPRK. The most famous is Charles Robert Jenkins, husband of Japanese abductee Hitomi Soga, now hospitalized in Japan. Two others - Private Larry Allen Abshier and Corporal Jerry Wayne Parish - are no longer alive. The fourth, Private First Class James Joseph Dresnok of Norfolk, Virginia remains in Pyongyang. Little is known about Dresnok except that he left South Korea for the North in August 1962 at age 21. He appeared with Jenkins in the North Korean propaganda film, "Unsung Heroes."

Filming is scheduled for September 2004.

In May and June 2004 British filmmakers Daniel Gordon and Nicholas Bonner travelled to Pyongyang, North Korea and met two US defectors, Sergeant Charles Robert Jenkins of Rich Square, North Carolina and Private First Class James Joseph Dresnok of Norfolk, Virginia. The two men had defected in 1965 and 1962 respectively and were keen to tell their story to the world.

As a result of a number of meetings and interviews between the British filmmakers and the US defectors, an agreement has been reached with the North Korean authorities to tell the full story of the four US soldiers who crossed the 38th Parallel in the 1960s and defected to North Korea. Of the four soldiers they were told Private Larry Allen Abshier and Corporal Jerry Wayne Parish died of natural causes in North Korea.

Gordon and Bonner had previously made two films in North Korea - the award winning documentary 'The Game of Their Lives', a story about the legendary North Korean Word Cup team of 1966 who produced the greatest shock in World Cup history, and 'A State of Mind', which followed the daily life of two schoolgirl gymnasts over a nine month period in the lead up to North Korea's mass games.

Both films were made with the full co-operation from the Korean Film Export Import Company' and in association with the BBC and have been broadcast worldwide. A State of Mind has been selected for the Pusan international Film Festival, in South Korea in October.

Gordon and Bonner's next film, titled 'Crossing the Line', will tell the full story of the defection of four US soldiers in the 1960s, including Dresnok and Jenkins. In an interview in June 2004, Dresnok spoke of his early years in North Korea: "We were under the supervision of the North Korean military. They took good care of us and they requested us to teach English to military personnel.

"I did not want to stay in DPRK at first. I wanted to go to Russia. Having crossed, after a few months, I began thinking it over and decided to remain.

"I'm glad I did, because about 10 years ago, Russia changed from socialism to capitalism. If I was in Russia right now, I would be out of work, I would find it hard to get a job. It would be the same if I returned to America. I find it more convenient to live among peaceful people, living a simple life.

"They are human here. The US military teaches you they are evil Communists, they have horns, they have fangs, they have red faces. I never believed such bullshit. Of course, there is an ideological difference, but that is the only difference."

Bonner, who has spent eleven years specialising in North Korea travel and cultural exchanges, acknowledged that this has to be the story of a lifetime and would make fascinating viewing - a US soldier who turned his back on the west and came as close to being a North Korean as any man. "We watched the footage of Jenkins leaving Pyongyang airport," stated Bonner. "He was holding a packet of cigarettes we gave him when we last met! But we knew that as big a story remained in Pyongyang. That story is

Dresnok."

Dan Gordon added; "We won several awards for the Game of their Lives, and all the indications are that A State of Mind will do even better. Yet 'Crossing the line' is set to blow everything else out of the water. For any filmmaker, this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, What will remain the same, though, is our approach to the story. We will continue to tell human stories without being judgemental."

When asked why he wanted to make the documentary on his life Dresnok told Gordon and Bonner; "'Let them know the truth I would appreciate it very much."

Kim Deok-hong, a former North Korean businessman who defected from North Korea along with former North Korean Workers’ Party secretary Hwang Jang-yeop in 1997, tried to hold a press conference at the Foreign Press Club at the Seoul Press

Center. However, as the police kept him from appearing in public place due to safety reasons, Kim held a press conference via Internet at his home. He said at the beginning of the conference, “I wanted to go to the venue of the conference, but the police told me that they cannot guarantee my safety if I go outside. So I have to meet you through the Internet.” Kim revealed his stance on recent issues like the court’s ruling in favor of Song

Doo-yul.

In regards to the ruling of Song Doo-yul, Kim said, “The court’s ruling is wrong. There is obvious evidence against Song. North Korean people know what he did in the North and that he learned Juche ideology in North Korea. And also, he was invited to late North Korean leader Kim

Il-sung’s funeral, to which high-ranking North Korean officials could not be easily invited.”

In connection with the explosion in the North Korean city of Ryongchon in April, Kim said, “I believe that North Korean leader Kim Jong-il himself plotted the incident. After the explosion took place, North Korean underground organizations spread leaflets saying that the explosion was schemed by the North Korean leader. Those North Korean anti-Kim Jong-il underground groups are organized into cells and dedicated to spreading leaflets to disclose the realities of the Kim Jong-il regime, he said.

An official at the Seoul Police Agency in charge of protecting Kim explained, “We persuaded him not to go outside because we have gotten information about threats to Kim, after his interview with the Japanese newspaper Sankei was printed.”

Some people point out, however, that the police banned Kim from holding a press conference in a public place because they were concerned that Kim might criticize the Kim Jong-il regime and the current South Korean government’s policies toward the North, considering the government did not permit Kim to visit the U.S. and has restricted Kim’s outside

activities.

No Bed of Roses for North Korean Defectors

The Straits Times (Singapore), August 1, 2004

MOST North Koreans go to South Korea with a vague 'South Korean dream'. But as soon as the excitement of arriving settles in, they face the realities of a free market economy in which nothing is free. Few of them succeed and, unable to integrate into the mainstream South Korean society, most end up depending on government support.

One of the luckier ones is Ms Lee Yae Seon, 39. She has been operating a beer pub in

Sanggye-dong with two other North Koreans for almost a year and is now making a small profit of about 1.2

million won (US$1,000) a month. But adapting to life in South Korea has not been easy for Ms Lee either.

In North Korea, she was an actress in the Bekdusan theatre group, operated by the army to provide entertainment and propaganda for its troops. 'When I came here, I knew I had to start all over again. But I was okay with that. I was happy to take charge finally of my own life,' said Ms Lee, who went to

South Korea via China in January last year.

The sheer joy of earning money and keeping it motivates her. 'If we can keep it up like this, someday I'll be able to buy a real car. It's a dream coming true, you know?' she said.

For Mr Yoon In Ho, 29, things are different. The former skier arrived in 1999. Initially, he tried modelling, but his North Korean accent and the cold treatment from South Korean co-workers made him quit after only six months. Having worked at a dry cleaner and as a security guard, he is now

considering further studies.

'I never felt accepted. And I constantly get this feeling that I'm being stamped as a second-class citizen,' said Mr Yoon.

Once, he overheard co-workers talking behind his back. 'One of them said that 'a North Korean does not know anything. They have to be sent back to kindergarten',' he said.

South Korean sentiment was perhaps best summed up by securities research analyst Baek Gil Wan. 'I do welcome them, but I am not sure how far I would go to help them, especially when it comes to using taxpayers' money to help them settle down in South Korea,' he said..//..

A study by the Korea Institute for National Unification revealed that 88 per cent of the North Koreans living in the South had an average income below the 1-million-won mark, compared to a South Korean's 1.7 million won..//..

While fewer than 10 North Koreans arrived each year up to the early 1990s, more than 1,000 have made the dangerous journey annually since 2002.

The comments of one defector might serve as an indicator of what many of these North Koreans can expect once they get here.

He said: 'The honeymoon was over as soon as I got here.'

Return to *North Korean Studies*

Return to *North Korean Studies*