Return to Articles by Leonid A. Petrov

Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Fire:

Russian Immigrants in China

by Leonid A. Petrov

(presented at the 14th Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia in Hobart, Tasmania 30 June ~ 3 July 2002)

The Russians who made a mass exodus from China after WWII lived their tragic lives in the course of the struggle of Great Powers for domination in East Asia. Behind every personal account, one could easily find the traces of global ideological confrontation and imperial ambitions. Russians who crossed the Chinese border at different times and under different circumstances all found themselves hostages of the grand political game which continued in the region throughout the 20th century. Three major events – the Civil War in Russia, the War in the Pacific, and the Cultural Revolution in China – proved equally cataclysmic for the life of the

Russians residing in Manchuria, Korea or East Turkestan. Russian immigrants participated in and harshly suffered from every clash which occurred between the Soviet Union, Imperial Japan and Nationalist China. Even after WWII the destiny of Russian migrants remained no less tragic.

As a result, one half of this Russian community had to look for a new home in Australia, America and elsewhere. The other half, voluntarily or under duress, returned to Russia through the system of Stalinist GULAGs. Those few who remained in communist China opened another page of the tragic story of Russian community in China.

Surprisingly, Russians did not disappear completely from the Chinese census books: these days,

among the 1 billion people inhabiting the People’s Republic of China, Russians still account some 13,500. But this petty figure cannot be compared with the quarter of a million which used to reside in China before 1945.

This paper sets the goal of answering two questions: What was it that forced the Russians to choose between the barbed wire of the Socialist Paradise and the fate of vagabonds in the West? And what happened to those who dared to stay in China after their friends and relatives had gone? Meetings and interviews with survivors and their descendants will help to complete the bitter story of Russian Diaspora in China.

Unapproachable wall for Bolshevism

The very first Russian settlements in China appeared in the late 19th century, when the Tsarist government started the construction of the south-eastern section of the Trans-Siberian railway terminating at the new Russian naval bases in the Pacific, Port-Arthur (Lyuishun) and Dalnii (Dalian or Dairen). In 1897, the new town of Harbin was established in Manchuria on the banks of the Sungari River. Harbin, where the headquarters of the East China Railway (ECR) Administration were situated, and the railway line was protected by 500 officers and 25,000 soldiers of the Trans-Amur Military District. The project enjoyed

extraterritorial rights. The Russian “zone of estrangement” in China included the lands within 25 on either side of the railway line; another 75 miles on both sides of the zone of estrangement constituted the “zone of influence”. As a result, during the first two decades, the population of Harbin and other main stations of the ECR was more Russian than Chinese.

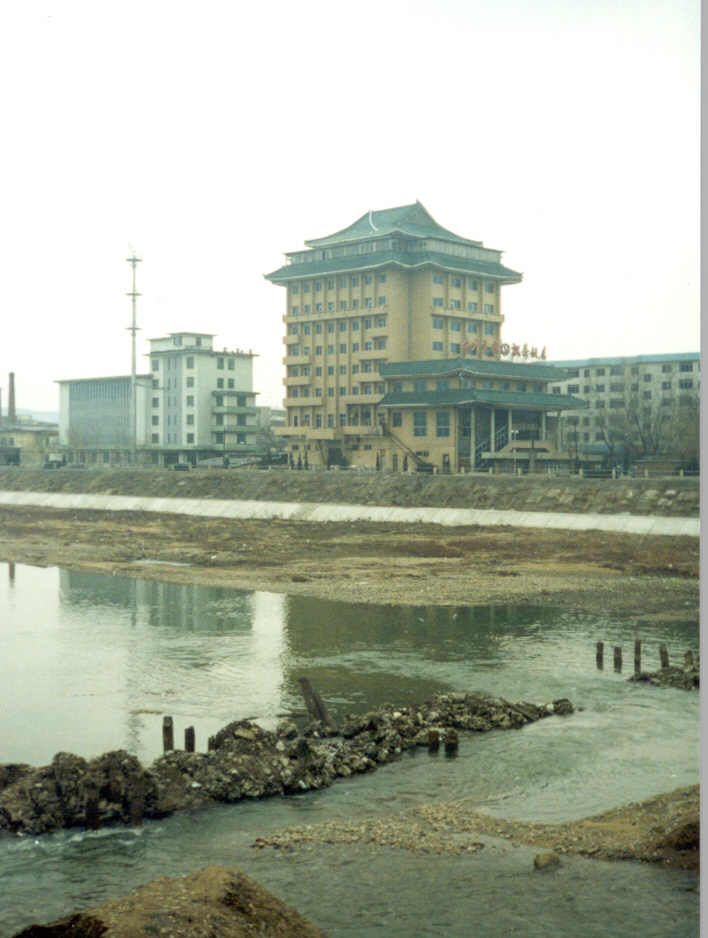

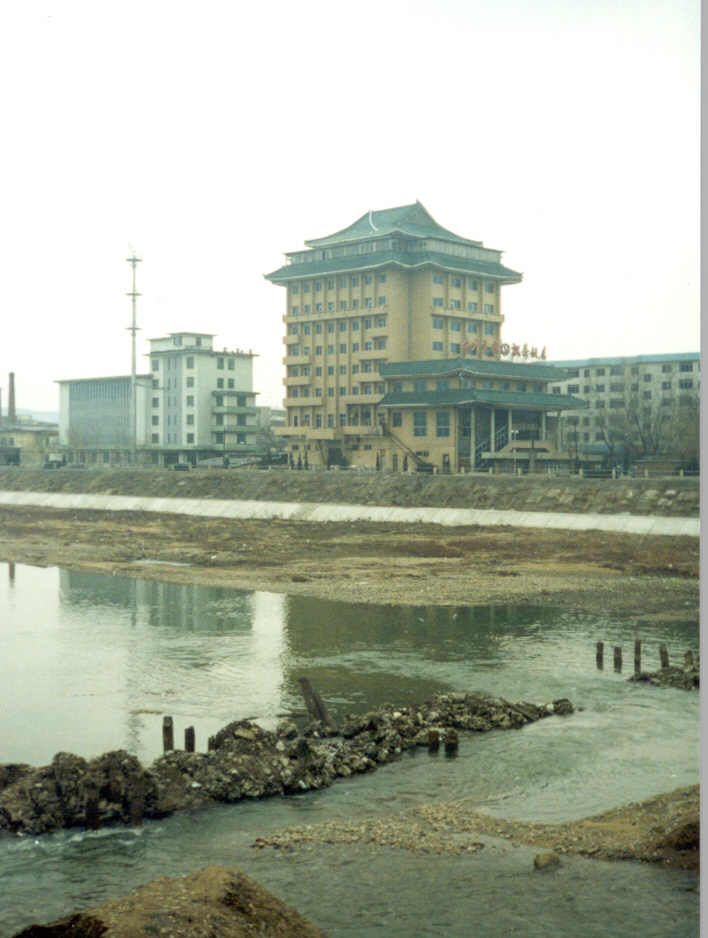

|

Remnants of the old Russian bridge for the never finished

railroad to Korea (Yanji, 1999)

|

The total assets of ECR in 1903 were estimated at 375 million golden roubles. It owned telegraph stations, coal and timber concessions, schools, hospitals, libraries and clubs. Apart from the railway line, the ECR possessed 20 steamer boats, piers and other property and equipment of the inland waterways. The Pacific fleet possessions of ECR Administration amounted to 11

million golden roubles. Dalnii and Port-Artur were not only naval bases, but promising transit points for international trade and initially they attracted even greater attention of investors than Shanghai. Nevertheless, after the disaster of Russo-Japanese war (1904-1905), Russia found itself deprived of both ports and most of its navy fleet in the Pacific.

In 1918, forced by the countries of Entente, the Chinese government closed its borders with Soviet Russia, and a fierce struggle for control over the Russian property in Manchuria began between Nationalist China, Imperial Japan, Bolshevik Government in Moscow and Russian Provisional Government in Siberia. |

Harbin was visited by the White Army’s Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Alexander Kolchak, whose purpose was to create anti-Bolshevik bases in Manchuria which would cater for the White Movement in eastern Siberia and Maritime Province. This plan received full understanding and enthusiastic support from both the Chinese and Japanese sides:

on 16 May 1918, a confidential agreement on "joint actions against the common enemy" was signed by both countries.

Significant financial assets were allocated for the Harbin government of Dmitry Horvat, the Chairman of ECR. Cossack Ataman Grigorii Semyonov, whose regiments arrived in Manchuria from Mongolia after the closure of Russian consulate in Urga, was promoted by Kolchak to the rank of General Lieutenant and appointed the Field Commander for the struggle against Bolshevism in the Far East. Provided with Japanese money, Semyonov (who himself was half Buryat and half Russian by origin), immediately launched the creation of anti-Bolshevik military groups. In the matter of months, his armed forces grew from 550 persons (mainly Cossacks and Buryats) to the army of 12,000

predominantly Chinese and Koreans. A close associate of Semyonov, Lieutenant Baron Nikolaus fon Ungern-Shternberg (who was half Hungarian and half German by origin) also took an active part in the struggle against Bolsheviks. To help them, Japan managed to involve the forces of Ussuri Cossacks under the leadership of Ataman Kalmykov.

In the strategic plans of Imperial Japan, the isolation of Soviet Russia from the rest of East Asia played the primary role. Three buffer states – Manchuria, Mongolia and the East Turkestan – were to become a huge security belt surrounding the USSR from the south-east. As a result, neither the Chinese nationalist government in Nanking nor their communist rivals in Guandong would receive direct military or advisory help from the Moscow-based Komintern (Communist International). The idea of an unapproachable wall for Bolshevism lying across the Asian continent found passionate support among the Russians residing in those regions. In February 1919, Semyonov and

Ungern-Shenrnberg unconditionally supported Japan in a move to create Sibirguo or Greater Mongolia, an enormous country which would cover the territory from Amur to Volga and from Baikal to Tibet.

In contrast, Admiral Kolchak demonstrated extraordinary stubbornness in negotiating with the Japanese. Refusing to trade in the Russian territories in exchange for support in the war against Bolsheviks, he preferred to pay for military supplies and provisions upfront from the Russian Imperial reserve of 645 million golden roubles which was seized by the Whites in Kazan in August 1918. Kolchak’s uncompromising position irritated the members of Entente, who were much more interested in gold and territories than in the prospects of White Movement. When Moscow threatened to blow the key tunnels on the Trans-Siberian Railway in order to prevent the White leaders from leaving Russia, the Allies arrested Kolchak and promptly handed him over to the Reds. Japan refused to undertake any attempts to rescue him. On 7 February 1920, Kolchak and the Prime Minister Peplyayev were executed by the Revolutionary Military Committee of Irkutsk, but the White Movement continued to roll eastward across Siberia.

Of those 505 tons of Russian gold which was seized by Kolchak, some 182 tons (worth 191 million golden roubles) settled in Japanese banks. General Semyonov himself forwarded to Japan 33,7 tons of gold worth 43,5 million roubles (172 boxes of golden nuggets and 550 boxes of golden coins). General Pavel Petrov entrusted another 1,300 kg (22 boxes of golden nuggets and coins) to the Head of Japanese Military Mission in Manchuria, Colonel Izome Ryokuro. In all these cases, official receipts were issued for the depositors. However, in order to destroy any proof of such transactions, Japanese Finance Minister Takahashi promptly ordered the Imperial Mint in Osaka to melt this gold into Japanese nuggets and coins. Later, in the 1930s, Semyonov and Petrov desperately tried to claim the right for this gold from Yokogama Bank and Chosen Bank, but to no avail.

Understanding the magnitude of the damage incurred by the White Movement, in April 1921 Moscow undertook active steps towards its elimination outside the Russian borders. The Red Army was dispatched to Mongolia with a mission to overthrow its provisional government and restore the constitutional monarchy. Trying to thwart these plans, Baron Ungern-Sternberg and 11,000 horsemen went north to the Trans-Baikal area and attempted to cut off the Soviet Russia from the buffer Far Eastern Republic. This campaign proved to be a failure: in September 1921, Ungern-Sternberg was chased back to Mongolia, captured and executed. These killings

opened the account of tens of thousands of Russian lives sacrificed during the 25 years of standoff between the USSR and Japan.

Left by the Allies, the anti-Bolshevik forces in Siberia and the Far East were driven to the southern corner of the Maritime Province. In autumn 1922, approximately 16,000 people crossed the Chinese border near Hunchun, and continued on to seek help in Harbin. Another 8,870 people under the command of Admiral Stark embarked on a fleet of old and rusty vessels to sail to the nearest foreign port of Wonsan. In Korea they were looked after by the Japanese Red Cross organization and then, ten months later, sailed further to Shanghai. On 25 October 1922, when the last vessel full of White officers and cadets left Vladivostok, the White Movement ultimately ceased its existence in Russia.

The hordes of destitute boat people fleeing from the oppressive regime raised little sympathy from local authorities. Instead of safe haven, the British rulers of Shanghai’s International Settlement requested the Russians to lower their three-color – a flag of the non-existent state – and gave them 48 hours to leave the waters of Huangpu River. But the stubborn asylum seekers resolutely said “no”, and set up their camps in Shanghai’s hinterland. It took them nearly three years to persuade the authorities to allow them to settle in the city. This decision, nevertheless, was dictated purely by political considerations: in the course of the ongoing Chinese Revolution

(1925-1927) the nationalist army of Chiang Kai-shek was approaching Shanghai. In these circumstances, experienced Russian officers and cadets seemed to be the best force to protect the city from rape and pillage.

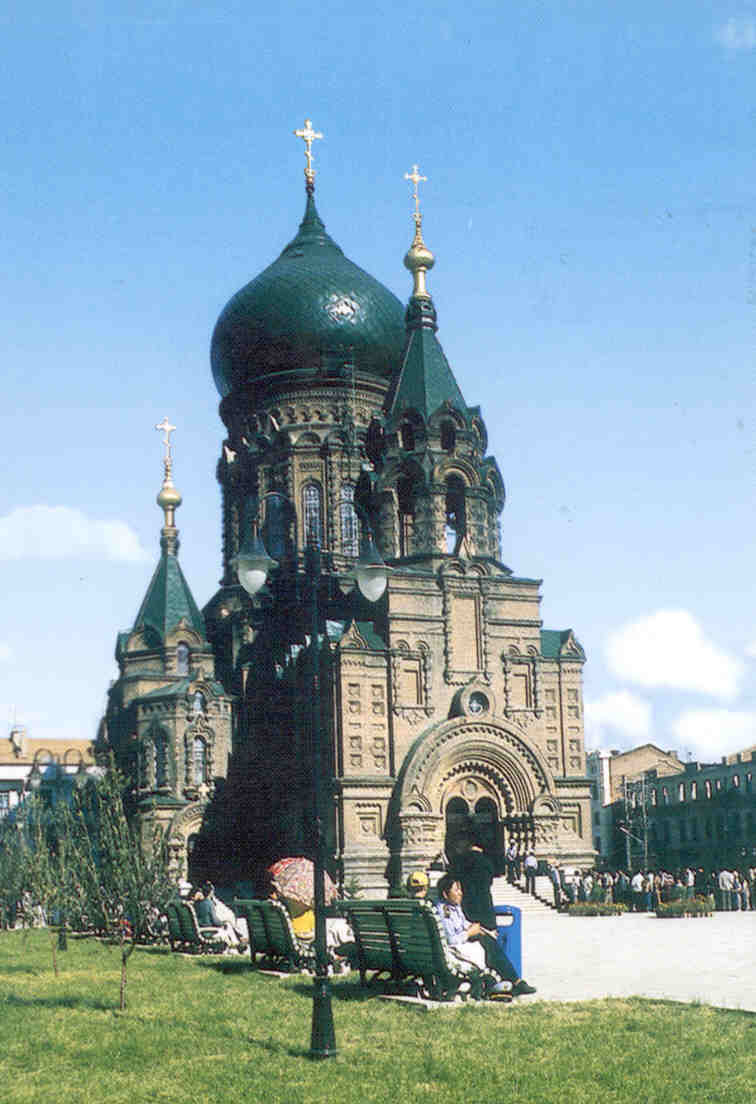

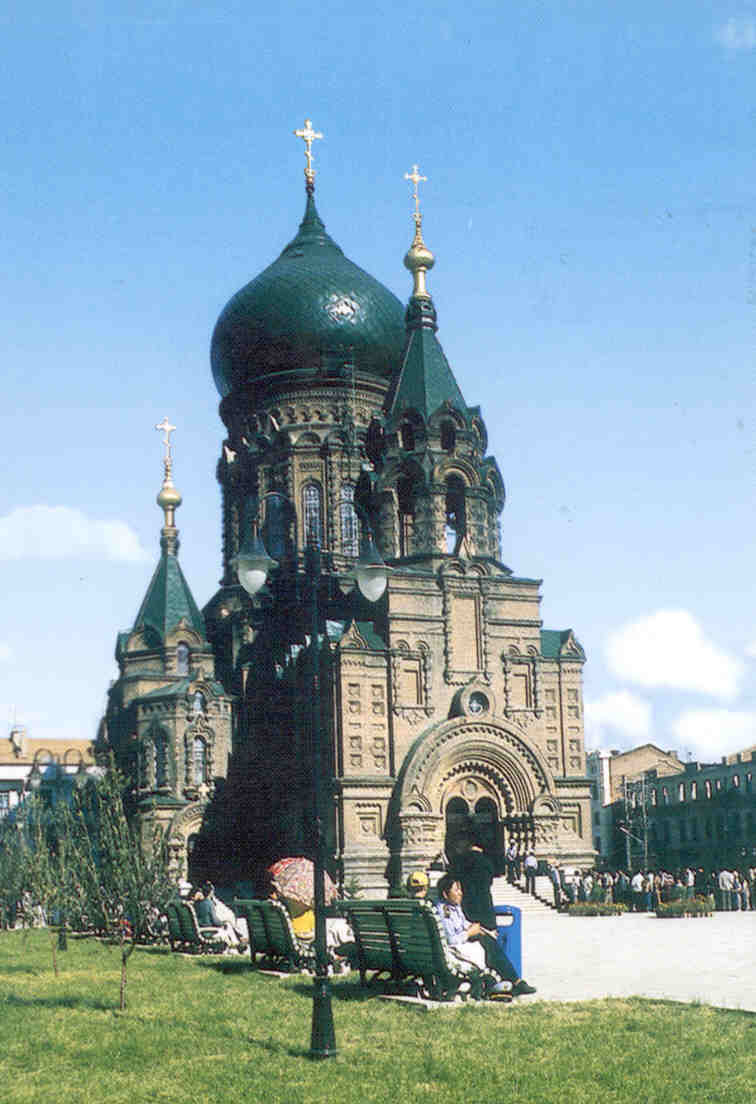

The volunteer Russian regiment, which was required to protect the International Settlement of Shanghai until the arrival of regular British troops, was formed on 21 January 1927 by General T. L. Gleboff. Only after that were the rights of Russian refugees in China formally recognized. The number of immigrants continued to increase. In hope of saving forces before returning home for the restoration of the "old regime" the armies of generals Anenkov, Dutov and Bakich also crossed the Chinese border and settled in Xinjiang (East Turkestan). The Russian language received wide circulation and was recognized by the local authorities. In large cities like Urumqi, Kuldja and

Chuguchak, Russian Orthodox churches, schools and newspapers were opened and Committees of Cossack Elders operated.

|

The number of Russian residents in eastern China and Manchuria was skyrocketing. While in 1893 only one Russian passport-holder was registered in Shanghai, by 1904 already several thousand Russians permanently lived there and by 1929 this figure reached 13,000. In the 1930s the Russian colony in Shanghai reached 20,000. As for Harbin, from mid-1920s until the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, its Russian population increased from 150,000 to 200,000 people.

|

The staff of the Russian Hospital (Harbin, 1930s) |

Under dual control throughout WWII

At the end of the Civil War (1918-1922), thousands of former White officers and their families, fearing Bolshevik retaliation, continued to flee to China. This time, refugees from the USSR were running from forcible collectivization, mass expropriations, political purges, famine and hopelessness. Thus, those who left the Soviet Union and found refuge in China during the late 1920s and early 1930s were largely apolitical, but very fearful of being repressed. Nevertheless, after crossing the border, Russian migrants continued to remain within the limits of Moscow’s control. Retaliations and eliminations of “dangerous” people continued

throughout the 1930s and 1940s.

Despite the plans and aspirations of imperial Japan, both Xinjiang and Manchuria became included into the sphere of Soviet political and economic interests. Japan, although always being a threat factor (real or magnified by propaganda), never intruded into Xinjiang. This fact brought a mortal blow to the anti-Bolshevik course and placed its leaders under the constant control of political and trade representatives of the Soviet government. As a result, activists of the White Movement were annihilated regardless of whether they cooperated with GPU or not.

The Russian regiment of Xinjiang, which was formed and led by the former imperial officer, Paul Papingut, effectively helped the local ruler, duban Sheng Shi-tsai, to suppress the vicious Dungan Uprising (1931-1933). These White “volunteers”, in fact, were refugees who refused to fight for the Chinese authorities at Urumchi until threatened with forced repatriation to Stalin’s Russia. In

1934 the regiment was disbanded and its leaders thrown into prison. Based on the trumped-up charges and false testimonies, some forty former White Russian officers were executed in 1937-1938. All of them were accused of “conspiracy for Japanese and British intelligence services” and attempts to create an “anti-soviet state” in Xinjiang. Amazingly, in 1942, Sheng Shi-tsai completely changed his policy and allied

with the nationalist forces of Guomindang. The Soviet power in East Turkestan was significantly reduced, while the US and British consulates were opened in Urumchi.

Nevertheless, until the late 1930s, the Soviet frontier guards and NKVD groups had a free hand in the territory of East Turkestan. Disguised under the Chinese Army uniform, they could cross the border and terrorize the local population. The Russian, Kazakh and Kyrgyz refugees fleeing to China were shot from the air; NKVD operatives could arrest anyone they did not like. Why did the Russian émigrés remain in Xinjiang? The ongoing war with Japan imposed severe movement control for those who wanted to move eastward. The stationing of the 8-th regiment of the Soviet RKKA (Red Army of Workers and Peasants) in Hami during 1930s and 1940s became another

reason. Given the constant presence of Dungan brigands, the long and dangerous trip across the Takla Makan and Gobi Deserts seemed almost impossible. Thus, rare

attempts undertaken by the Russians to escape the massacre and relocate to central and eastern China often finished tragically. Only a handful of Russian families managed to reach Tianjin after their relatives in Xinjiang were forced to pay ransom to bandits.

NKVD did not spare even its own agents working in China. An insight into the style and methods of work of the Soviet establishments in Xinjiang is given in The Empire of Fear (1956), a book written by the former Soviet spymaster in Australia, Vladimir Petrov. In 1934, the young cryptographer Petrov was dispatched to the city of Yarkand, southern Xinjiang. There he witnessed numerous massacres of Russian immigrants and

local dissidents. Even the Chinese governor of Yarkend, who himself had been spying for Moscow, was brutally “neutralized" when his loyalty to the USSR became questioned. Atamans Dutov, Bakich and Annenkov were abducted from Xinjiang, put on a show trial and perished. Released from correctional custody, their junior officers began to collaborate with the Soviets. By the time of the outbreak of WWII, Xinjiang had become a virtual territorial extension of the Soviet Union.

Among the survived witnesses of the Soviet policies in Xinjiang are the Pon'kin and Porublev families, both currently residing in Australia. In his memoirs, The Path of my Father

(1997), Alexander Ponkin described the circumstances of his two arrests and imprisonments in 1934 and 1938. In both cases the charges were fabricated by the Soviet Consulate in Urumchi. Pon’kin’s testimony depicts the atmosphere of life in Xinjiang as full of fear, reprisals and punishments of "defectors" and "traitors". This account is corroborated by the travel notes made by a Turkish citizen, Ahmad Kamal, in his Land without Laughter (1940) where he narrated the horrors of Xinjiang prisons and torture chambers. Porublev, in his turn, estimates that of 20,000 Russians populating Xinjiang in the 1930s and 1940s, some 1,500~1,800 became casualties of the Dungan

Uprising (1931-1933) and Chinese War (1944-1945). Both wars were particularly savage, being fought on ethno-religious grounds. Prisoners were routinely tortured, but Russians, as a rule, were just killed without torture.

|

|

In Manchuria, conditions of life for Russian immigrants were hardly better than in Xinjiang. In 1924, the top managers of ECR were replaced by the staff arriving from the USSR. Working under direct guidance of the Komintern, the new Soviet managers were more concerned about the communization of China than about the technical and business issues of the railroad. Under the fear of being sacked, the old staff of the ECR was forced to assume Soviet citizenship. Those who refused were encouraged by the Chinese government to take Chinese passports. Nevertheless, many preferred to abstain from either choice and remained the citizens of the non-existent Russian Empire holding the

special émigré passports. Regardless of their choice, all three groups were subjected to equally grim experiences.

As it was demonstrated in Shanghai and Urumchi, White Russian officers were good soldiers and insightful military advisors. For this, they were often employed by the cliques of local warlords (Zhang Zuo-lin, Feng Yu-xiang, etc.) desperately trying to unify northern China under their rule. Poorly armed, Russian units profusely watered Chinese soil with their blood while sustaining heavy losses from the regular armies. Another activity where Russians were often employed was the risky business of body-guarding

and protection of local population from bandits and kidnappers. |

Pursued by the new puppet government of Manzhouguo from 1933, the policy of cultural association of all races residing in north-eastern China could not leave Russian community untouched. Russians cheerfully welcomed the arrival of Kwantung Army in Harbin in early 1932. They believed that the Japanese would bring them a better life, order and protection from the Soviet intrusion. Nevertheless, the strategy of Tokyo was based on

ideological neutralization of the local population of Manchuria. Instead of disbanded political parties and associations, all Russian émigrés were enlisted to join the only official political party, Manchuria Imperial Concordia Society [Manchu Teikoku Kyowakai]. Kyowakai (or Xihehui) was a political organization which avoided both the character of a political party and the aim of securing political power. It functioned simply as a behind-the-scene organization which complemented the activities of the puppet government of Manzhouguo, striving toward the achievement of the ideal of "nation building" [kenkoku].

|

The threat of imminent military clash between Japan and the USSR demanded a constant input of information about the state of Soviet military preparedness. Under the pretext of help to Russian émigrés to preserve their cultural identity, Kyowakai was running various training programs for future agents and terrorists whom Japanese intelligence began to infiltrate to the Soviet territory. The remaining forces of anti-Bolshevik resistance among the Russian Diaspora were quickly depleted by the Japanese who often dispatched the youngsters to certain death. Those who managed to return from their mission were often interrogated by Japanese

counterintelligence as if they had already been recruited by the NKVD to spy against Japan. Tortures and killings became normal practice and hardly differed from those Stalin employed against his own people in 1937-1938.

|

Russian and Japanese engineers at the New Year celebration (Eiko, 1942)

|

Some “leaders” of the Russian Anti-Communist Committee in Tianjin were real Soviet agents infiltrated into the Diaspora. Their mission was to stir up the Russian community against the Japanese. Many Russians accepted for service in Japanese and Manchurian police and gendarmerie were corrupt and used official power and intelligence to extort money from their own compatriots. As a result, many innocent people among the Russians were kidnapped, tortured, maimed and finally, if the ransom was not received in time, killed.

In such circumstances it was difficult to presume that Russian émigrés would continue to feel any sympathy toward Japan and its policies. The situation was aggravated with the sale of the ECR to Japan in 1935. Accused of collaboration with communists, many rushed to return to the USSR. Previously empty, the Trans-Siberian trains became chock-a-block with people striving to escape the terror of Japanese police and their Russian henchmen. But the return to motherland would give them no relief. Once on the Soviet territory, most of repatriates were accused of being Japanese spies, sent to Gulags or executed. Some were sent back to Manchuria for espionage missions that would

make the general situation even more confusing.

It seems that the opening of the notorious Camp Refuge, which accommodated Japan’s Germ Warfare Unit 731, at Pinfan station only 20 km from Harbin was not a coincidence. In the late 1930s, Japanese experiments with plague and anthrax required more live material of the “white race”. Among the guinea-pig prisoners (400-600 new people each year) there were many Russians, predominantly defectors from the Soviet Union. Almost three hundred NKVD officers who escaped from the USSR following the defection of their boss – the Chief of NKVD in the Far East, Commissar Genrikh Lyuskov – finished their days in Camp Refuge.

|

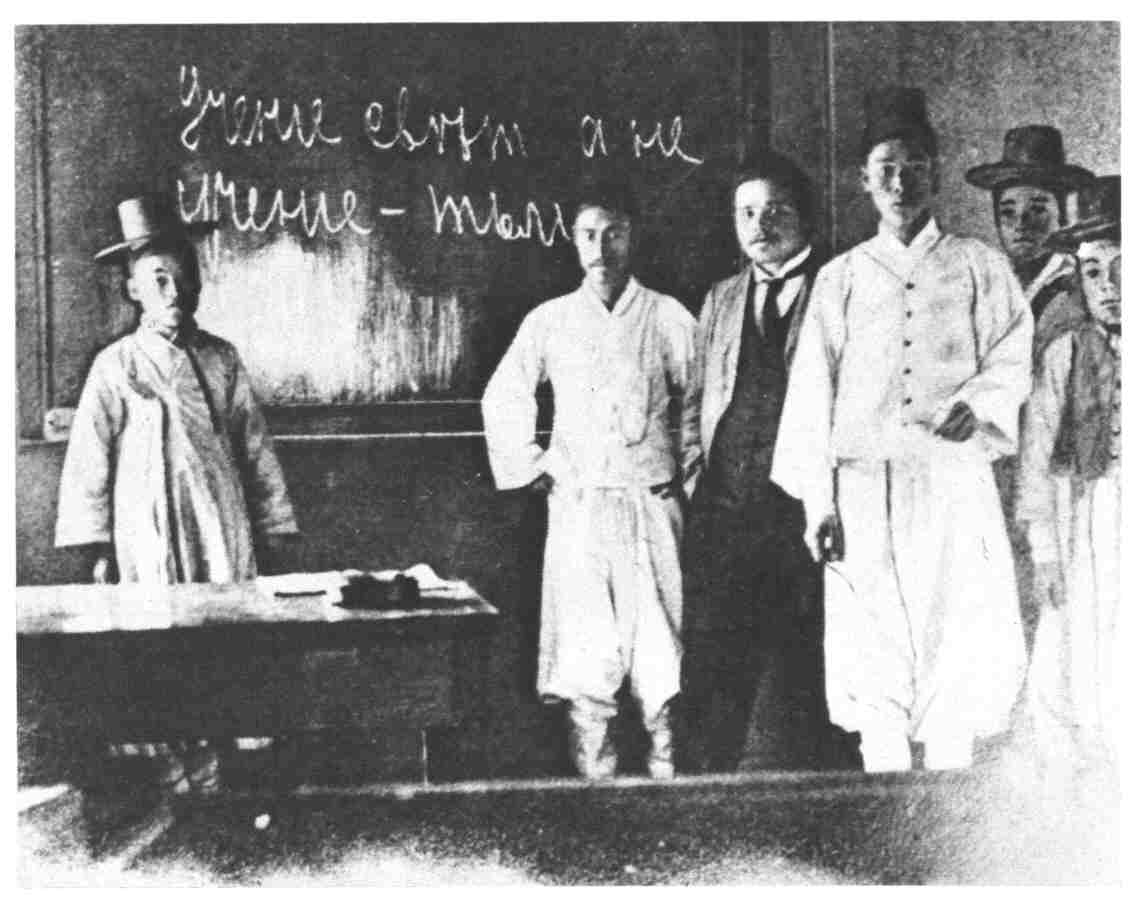

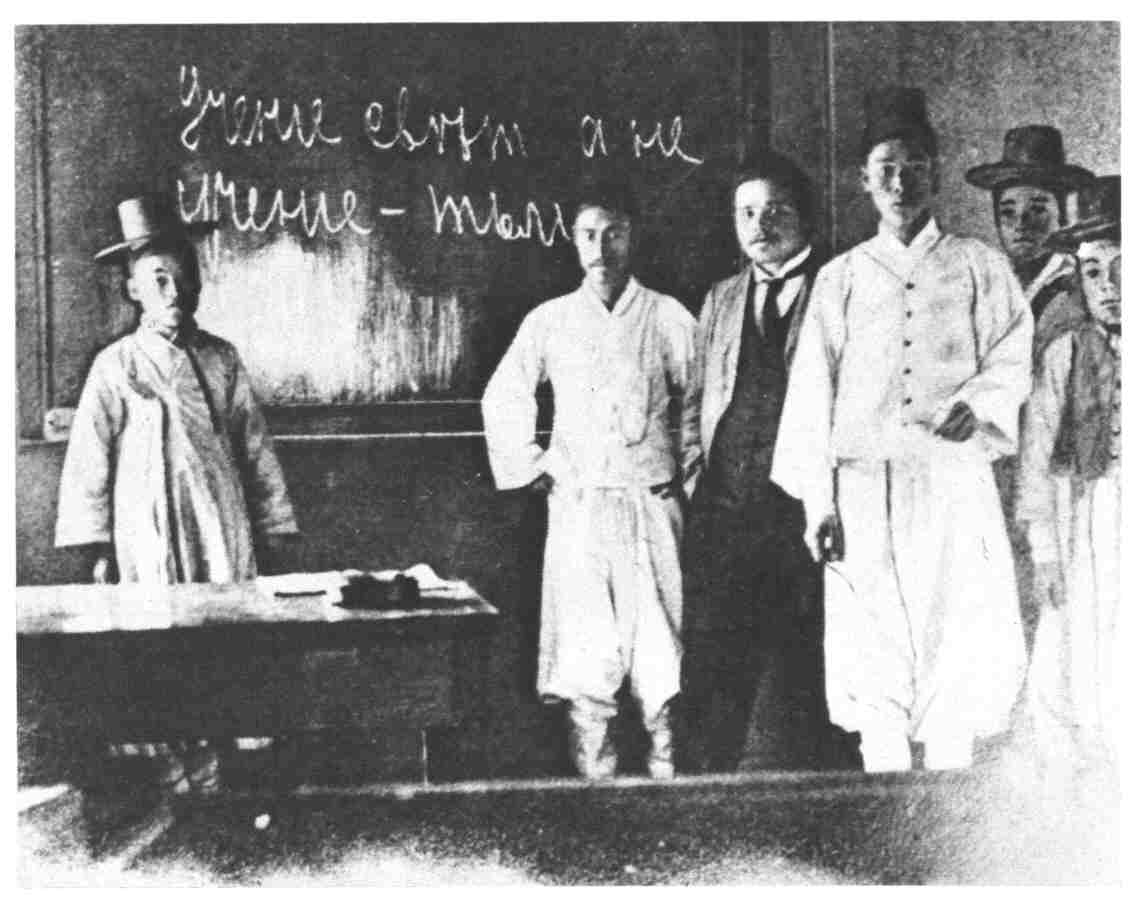

It must be mentioned, though, that the Russian population in China and Manchuria never stopped being treated as “foreigners” and, thus, enjoyed certain privileges inaccessible to other ethnic groups. Unlike their compatriots in Xinjiang, Russians could travel, seek employment, purchase and sell land anywhere around the newly-rising empire. The high level of education and professional skills allowed many of them to gain prestigious positions at the military factories, police, schools and hospitals. The teaching of Russian was actively supported by the authorities in Manchuria and Korea.

|

Innokentii Davydov teaches Russian in Korean school (1930s) |

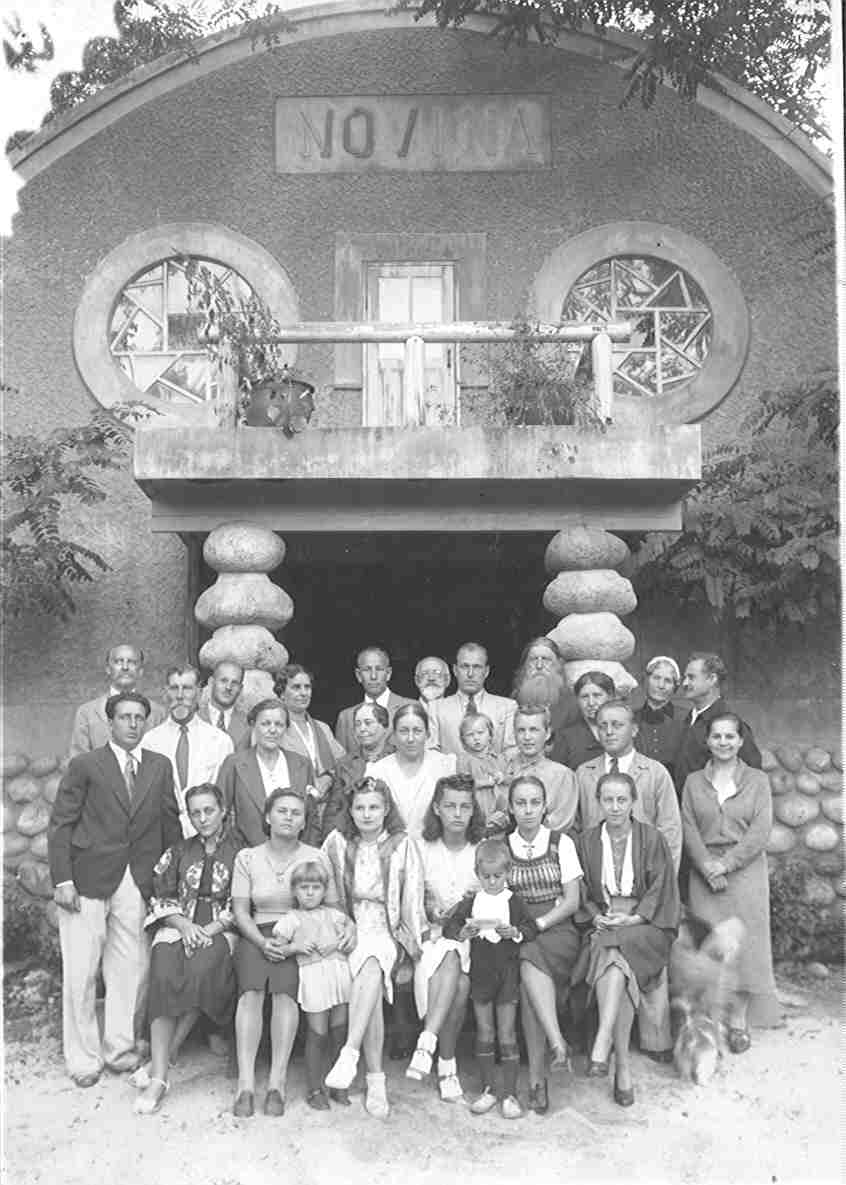

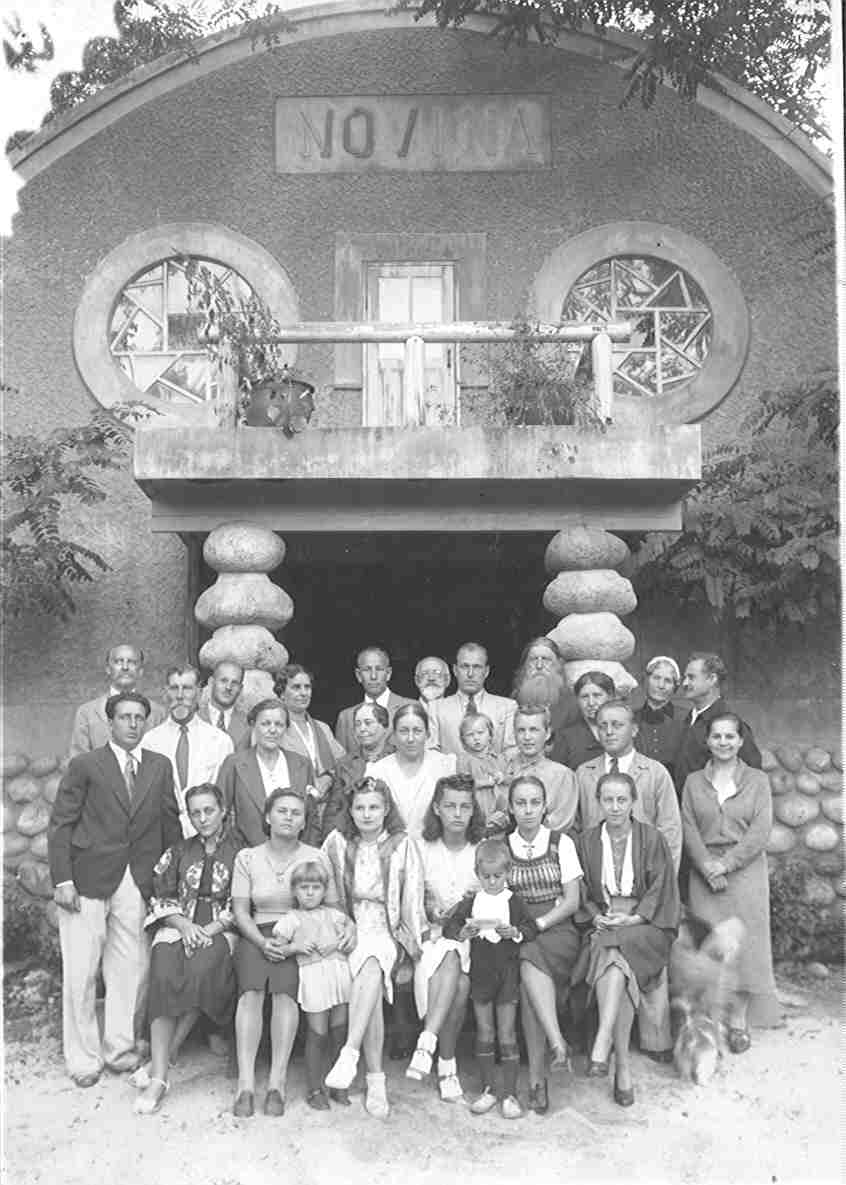

Agriculture, hunting and hospitality became other sectors where Russian émigrés could demonstrate their skills. In northern Korea, at the Kyongsong hot sprigs near port Ch’onjin (Seisin), the Yankovsky family set up a red deer farm and two resorts, "Lukomorye” (“Curved Seashore") and “Novina”. In the late 1930s, affluent and middle-class Russian families from Harbin, Tianjin and Shanghai would spend their holidays on the north-eastern coast of Korea. Yurii Yankovsky, the head of the family, became known as the best hunter on tigers in East Asia and often hosted guests from all over the world. For their contribution to the development of the image of Korea, the Yankovskys gained respect and protection of the Japanese General Governor of Korea.

Resort “Novina”, its guests and hosts. (Hamgyong Pukto, 1942)

|

Nevertheless, behind the facade of prosperous and happy life, Russians in Manchuria, Korea and China felt constant fear for their future. In 1932, their search for certainty brought to Manchuria an international commission of the League of Nations led by Lord Bulwer-Lytton. But Japan rapidly isolated those Russians who wanted to appear before the commission and finally walked out of

the League of Nations following the debate on Lytton’s report. Since then, Russians in Manchuria felt like hostages in the hands of Japanese military. The

wartime regime imposed even more restrictions on personal freedoms and economic activity. Every change in the international situation continued submitting the Russian Diaspora to the geopolitical plans of Japan.

Throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, Soviet propaganda did its utmost to lure the fugitives back to the USSR. A new generation Russians born in China, Manchuria and Korea grew up under the blandishments of the underground Soviet radio station called “The Fatherland”. |

Day by day its programs appealed to patriotism and devotion of listeners, swearing that “all immigrants were forgiven by their fatherland”. Calling them “brothers and sisters”, Stalin’s propaganda encouraged the Russian population of Manzhouguo to assist Soviet troops when they get there to liberate the area from Japanese oppression. In the moments of desperation such words could not but create certain

effect.

Those who remained immune to the exhortations of the Fatherland fell pray to Japanese propaganda. Until the very last days of war, Japanese press carried exaggerated reports regarding the victories in China and the Pacific. Many Russians were inspired by the proximity of war against the USSR and joined the Kwantung Army, assuming the new motto “to live and die with Great Nippon” and relentlessly pledging loyalty to Hirohito. The motives which prompted them to assume such extreme views were a mixed desire for revenge against Bolshevism and the instinct of self-preservation in the midst of an aggravated international situation. Very few people could anticipate the abrupt end of Japanese domination. But even the well informed could do little to avoid the chaos of the short but dramatic war between the USSR and Japan.

Soviet invasion and the Cultural Revolution

Despite the promises to forgive everyone, when the Soviet Army entered Manchuria and northern Korea on 9 August 1945, all Russians residing in the occupied territory were automatically declared "enemy collaborators”. Using the hit-lists prepared in advance, the NKVD and SMERSH (“Death to Spies”) units arrested and dragged to Siberia more than 10,000 Russians, mainly men who had served with the White and Japanese Armies. The

pardon was promised to General Semyonov, who then resided outside the zone of occupation in Dalian, in case of his voluntary surrender. But as soon as he appeared in the hands of NKVD officers, Semyonov was sent to Khabarovsk and, after a short show-trial of “White bandits”, was shot along with his former associates. Thus, the remnants of the White Movement abroad were eradicated.

A similarly crafty policy was pursued by the Soviet counterintelligence in northern Korea. Although some members of the Yankovsky family, inspired by patriotic feelings, volunteered to work with NKVD and SMERSH as interpreters, by mid-1946 many of them were interned as “notorious collaborators” and “landlords”. The elderly Yurii Yankovsky was sent to Siberian Gulag where he died ten years later. His two sons outlived him but were

locked in the USSR for many decades. Only in April 1948, when the Soviet occupation of Manchuria and Korea was ending, many Russian émigrés took advantage of the general chaos and confusion and escaped southward. Many found refuge in Seoul, Shanghai and Hong Kong and then went further to Chile and then to America.

Russian immigrants did not have much time to spare because in October 1949 the communists with their people’s tribunals took power in China and urged all “foreigners” to repatriate. For Russians remaining in China, it became an increasingly difficult time. Soviet consulates could not stop praising the “new life” in the USSR and encouraged Russian youth to receive Soviet passports and come “to build socialism". Such propaganda campaigns often resulted in the splitting of families, where indoctrinated children would aspire to return to the motherland while their cautious parents would prefer to seek safe haven in the West. In Xinjiang, the Soviet

Consulate General in Kuldja ran the province until 1949 with the result that very few local Russians made it to Australia and other Western countries.

In 1947, some 3,000 Russians received Soviet passports, and by two steamships departed from Tianjin to the nearest Soviet port of Nakhodka. Instead of the promised red carpet and orchestra, they were met with barbed wire and rifle shots; some were executed on arrival, the rest were sent to the Gulags. Only after Khrushchev formulated his de-Stalinization policy in 1956, were most repatriates pardoned. Nevertheless, they still lacked the right to reside in European Russia.

Using their native wit, the other half of the Russian community hurried to leave China on the ships heading to where the International Organization for Refugees’ Affairs had its camps open. The largest transit point for Russian refugees was set up on the Tubabao peninsula near the small city of Guyan, Samaras Island of the Philippines. Some 5 thousand people were to spend months and years in a tent village while awaiting a visit of immigration officers from America, Canada or Australia. At that time, Australia was still pursuing its racist “white Australia policy” and for this reason would not accept racially mixed families and elderly people. Thus, for many Russians who had spouses of Asian origin or dependent children with mixed blood the way to Australia was barred.

In the late 1950s, life for those Russian émigrés who remained in communist China became intolerable. The final exodus of Russian population again divided into two streams: the repatriates, returning straight to the virgin lands of Kazakhstan, and the refugees seeking asylum in any Western country where a viable sponsor could be found. Even after that some Russian families remained in Xinjiang, North-East China and North Korea. But those who did not manage to escape before the early 1960s were left there until the end of the Cold War.

Among the rare survivors from the menace of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1969) can be named the family of Innokentii Davydov. Descendant of the noble Russian clan famous for its role in the Decembrists Uprising of 1825, Davydov arrived in Manchuria in early 1920s with General Semyonov. He firmly refused to assume any other citizenship and remained White Russian. As an activist of the Kyowakai, he taught Russian and closely cooperated with the Japanese until the end of WWII.

Davydov was forced to work for the NKVD as an interpreter during the Soviet occupation of Manchuria, but miraculously escaped imminent arrest by fleeing to the south with his Korean wife. With his Asian wife and mixed blood children he had little chance of finding refuge in Australia or other Western countries. Therefore, his children received education in China and North Korea where they planned to arrange their future life.

The half of the family which remained in the DPRK fully experienced the terror of Kimilsungist reprisals and purges against “impure elements”. Davydov’s elder daughter, Elena (Pak Myong-sun), spent eleven years in concentration camps and prisons because of her husband, a North Korean poet who was accused of an assassination attempt against General Kim Il-sung. In the “socialist paradise” Korean-style, Elena’s children were born and grew up in the underground cell of Hongch’on penal complex, Northern Hamgyong Province. They were rarely allowed to see the sun. However, it was Kim Jong-il, the son of bloody dictator, who launched his image building campaign in 1975 and saved

a dozen of unjustly imprisoned luminaries, including Elena and her husband Kim Ch’ol.

|

As for Davydov’s younger sons, they left Northern Korea in early 1960s and joined him in China shortly before the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1969). Living not far from the Soviet border in south-eastern Manchuria, the Davydovs found themselves in the epicenter of Maoist political campaigns against the USSR. Davydov was arrested and charged with espionage for the Soviet Union. In 1968, his youngest son, Vladimir, was recruited to the Chinese People’s Army and sent to serve near the island of Damansky – the focal point of the Sino-Soviet border conflict – where he was wounded.

During the Cultural Revolution, Davydov’s second son, Sasha, was a commander of the revolutionary Red Guards corps. The Chinese authorities wanted to use him at the court where his father was being tried. Sasha was summoned and forced to give his consent for the proposed death sentence to his own father. The verdict was later cancelled, but soon after that Davydov the senior died of heart attack. It is remarkable that after the death of Mao in 1976 and the overthrow of the Gang of Four the death penalty was now chasing Sasha, a person with the Red Guard past… |

Monument to the Soviet Army Liberation in Tumen.

Built by Davydov and his sons in 1946. |

* * *

Astonishing but invariably tragic stories of Russian immigrants in China are endless. Without exaggeration one can say that the whole history of this branch of Diaspora is a mix of incessant fears, misfortunes, struggles and frustrations which stretched throughout some six decades of the twentieth century (1917-1977). Moving to the suburbs of civilization – either the barren steppes of East Turkestan or Manchurian taiga – Russian refugees fled from one oppressive regime only to find themselves under another. For more than half a century they remained hostages in the hands of one hostile power or another. Whereas the USSR, Japan and China were preparing for war against

each other, the role of Russian community was reduced to the choice between decoy and gun fodder.

However, it would be mistaken to disregard completely the role which Russian community played in the Far Eastern politics. Each belligerent state paid special attention to the Russian immigrants residing in the area which one day was to become a theatre of war. They encouraged the teaching of Russian at schools, sponsored the vernacular press, and created various cultural associations. But the nature of such interest and support was a mere reluctance to allow the adversary to take any advantage of this ethnic group. In such circumstances, the quickest possible annihilation (by killing or deportation) of the Russian community in China was in the best interest of each side

involved.

Those who survived the horrors of WWII soon found themselves on the forefront of the Cold War. The Sino-Soviet ideological conflict continued to push Russians out of China. But many of them simply did not have a new place to go. The return to the USSR was always considered suicidal, while many countries of the West kept their doors closed. Finding themselves between the hammer and the anvil, the Russian Diaspora in China was doomed to vanish.

Return to Articles by Leonid A. Petrov

Return to Articles by Leonid A. Petrov