"Power to the ISS!"

What's the most important resource on the International Space Station? Electrical power!

|

Electrical power is arguably the most critical resource for the International Space Station (ISS). The very air in the ISS is created by splitting water molecules using electricity. Meanwhile, spare oxygen is stored in electrically pressurized tanks. Electrical power is arguably the most critical resource for the International Space Station (ISS). The very air in the ISS is created by splitting water molecules using electricity. Meanwhile, spare oxygen is stored in electrically pressurized tanks. Left: On the ISS, electricity not only provides the essentials - like breathable air - but also familiar comforts like clean-shaven faces.

Electricity keeps the ISS and its crew alive: It powers the air and water systems, keeps the lights on, pumps liquids for recycling, warms meals, runs computers. It even lets crewmembers talk to school children by Ham radio! Indeed, electricity does it all for humanity's home in space.

Supplying reliable electricity to a home gliding 350 km above our planet is no small challenge. After all, it's not as though the crew can drop a power cord down and plug it in to the city grid! And transporting fuel up from the surface would be far too expensive because of the high cost of launching rockets.

In Earth orbit, the most practical source of energy for the ISS is sunlight. Fortunately, solar power is plentiful. The Sun radiates a huge amount of energy into space: 4 x 10 23 kilowatts (kW), which is a 4 followed by 23 zeros, or about a billion billion times the electricity production capacity of all human industry. Our planet receives only about a billionth of that energy, but even this small fraction of the Sun's output represents a large dose of power.

"If we turned all the water in Lake Erie into fuel oil and burned it all in a single second, we'd produce about the same amount of energy as we get from the sunlight that strikes Earth in one day," explains Sheila Bailey, a research physicist at NASA's Glenn Research Center (GRC) in Cleveland, Ohio.

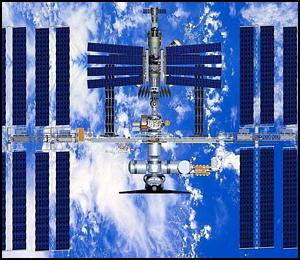

Above: The solar arrays are the most prominent feature of the International Space Station - and arguably the most important!

While some people (among them Wehrner Von Braun) have suggested that "solar collectors" could use the heat of concentrated sunlight to produce steam to turn turbines - much as electricity is produced here on Earth - photovoltaic cells remain the most practical way to extract power from sunlight in space. The Glenn Research Center developed the highly-refined photovoltaic (PV) technology that is being used on the ISS.

These cells are mounted on eight large, wing-like structures called solar arrays, each measuring 34 m long and 11 m wide (112 ft. x 39 ft.). The arrays together contain a total of 262,400 solar cells and cover an area of about 2,500 m2 (27,000 sq. ft.) - more than half the area of an American football field! A computer-controlled gimbal rotates to keep the arrays tilted toward the Sun.

But the Sun is not always "up," because the ISS spends almost half its time in the shadow of Earth! The spacecraft is in eclipse for up to 36 minutes of each 92-minute circuit around our planet. During the shadow phase the space station relies on banks of nickel-hydrogen rechargeable batteries to provide a continuous power source.

Left: Banks of rechargable batteries supply power to ISS systems while the space station is in Earth's shadow. Left: Banks of rechargable batteries supply power to ISS systems while the space station is in Earth's shadow.Those batteries consist of thirty-eight cells connected in series and packaged together in an enclosure that monitors temperature and pressure. The unit is designed to allow simple removal and replacement. The batteries, which are recharged during the sunlit phase of each orbit, are expected to last more than 5 years based on extensive testing at GRC, according to David McKissock, a power management systems analyst at Glenn.

Switching back and forth between solar-generated power and stored battery power was a challenge for designers of the station's power system. The entire electrical power supply has to be switched smoothly twice each orbit, distributing reliable glitch-free current flow to all outlets and devices.

"The result of this carefully managed process is 110 kW of power available for all uses," McKissock says. "After life support, battery charging, and other power management uses [take their share], 46 kW of continuous electric power are left over for research work and science experiments. That's enough to run a small village of 50 to 55 houses."

ISS power is a bit different from the electricity delivered to homes on Earth, though. Rather than the familiar alternating current (AC) that courses through city power grids, the ISS runs on direct current (DC) power. Devices from Earth that operate using direct current - such as portable CD players or electric razors - are well-suited to the station's 120-volt DC power systems; others require an AC adapter.

There's more to power management, than simply choosing AC or DC. Two important effects of power generation in space must be dealt with before the ISS can be a safe, working system.

Above: This astronaut working on the heat dissipating system must beware the possible dangers associated with producing large amounts of electricity in the plasma environment of low-Earth orbit.

For one, storing electricity in batteries and managing its distribution builds up excess heat that can damage equipment. Such heat must be eliminated, so the ISS power system uses liquid ammonia radiators to dissipate the heat away from the spacecraft. The exterior radiator panels are shaded from sunlight and aligned toward the cold void of deep space

A second side effect could be dangerous for the astronauts themselves if not properly managed. The station's solar arrays carry a strong electric field. At the same time, the ISS is zipping through the low-density plasma that permeates low-Earth orbit (LEO).

A plasma is a gas filled with charged particles that respond to electric fields - like the ones around the solar arrays. As a result, the hull of the ISS becomes highly charged. Space-walking astronauts could suffer shocks if they touch the metal hull of the station without taking proper precautions. [more information]

To counter these problems, GRC developed devices such as "plasma contactors," which neutralize the plasma charge on the ISS hull, and "circuit isolation devices," or CIDs, which enable a spacewalking crewmember to remove power from selected circuits so that the ISS power system umbilical cables can be safely attached. Without CIDs, large portions of the Station would have to be powered down during some spacewalks. To counter these problems, GRC developed devices such as "plasma contactors," which neutralize the plasma charge on the ISS hull, and "circuit isolation devices," or CIDs, which enable a spacewalking crewmember to remove power from selected circuits so that the ISS power system umbilical cables can be safely attached. Without CIDs, large portions of the Station would have to be powered down during some spacewalks.Above: This plasma contactor unit acts as an electrical ground rod that dissipates surface charges on the ISS. Credit: GRC. Thanks to technological innovations such as these, the lights are always shining brightly - and safely - on the International Space Station. And NASA engineers can confidently declare, "Power to the ISS!"

|

Credits & Contacts

Author: Gil Knier, Patrick L. Barry

Responsible NASA official: Ron Koczor

|

Production Editor: Dr. Tony Phillips

Curator: Bryan Walls

Media Relations: Steve Roy

|

The Science Directorate at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center sponsors the Science@NASA web sites. The mission of Science@NASA is to help the public understand how exciting NASA research is and to help NASA scientists fulfill their outreach responsibilities.

|

|