We have established that wet crude oil flows in a pipeline as a partial emulsion. The degree of emulsification (emulsification index) depends on the flow history, particularly the devices through which the fluid has passed. High-shear devices such as centrifugal pumps and control valves exacerbate emulsification. We will now examine the factors that determine the emulsification effect of various devices. The intention is to develop analytical relationships for quantifying the emulsification effects.

We build a pipeline to transport fluid from one point to another. However, we nearly always install, as part of the pipeline system, various items of equipment to assist in realising that objective. Except where we have the benefit of gravity flow, a pump is usually required at the inlet to a liquid-carrying pipeline. The pump provides the motive energy for the liquid. Often, we wish to measure flow in the pipeline. For this, we install a flowmeter which could be based on an orifice plate. If we also wish to control the flow rate, we install a control valve. The pump, orifice plate and the control valve are examples of devices in the system. Trivial as it may seem, the pipeline itself is a device. A device, in our context, is any item through which the fluid flows and which may act on the fluid in any manner dependent on the device characteristics. Each of the items of equipment we have just mentioned has its characteristics - a function that describes its effect on the fluid being transported.

In addition to the primary intended role, pipeline devices always have an unintended effect on the fluid. One of these effects in the case of oil/water flow is the break-up (by shearing) of the dispersed phase into droplets in the continuous phase - emulsification.

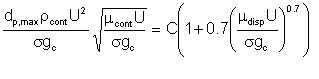

There is little documented research on the subject of how emulsification relates to the extent of shear. A pointer is an equation proposed by Sleicher. According to Sleicher, for fluid travelling in a pipe at velocity v, the maximum diameter of the dispersed phase cannot exceed dp,max given by

| Eqn 4/1 |

where

| gc = | gravitational conversion factor, 4.18 (108) (lb. mass) (ft.)/(lb. force) hr2 |

| C = | 43 (dt = 0.0417) or 38 (dt = 0.125), with dp,av = dp,max/4 for high flow rates, and dp,max/13 for low velocities. |

| V = | superficial velocity, ft./hr. = cu.ft./(hr.)(sq.ft.) |

| μ = | viscosity, lb. mass/(ft.)(hr.) = 2.42μ' |

| μ' = | viscosity, centipoise |

| σ = | interfacial tension, lb. force/ft = 6.85(10-5)σ' |

| σ' = | interfacial tension, dynes/cm |

| ρ' = | density, lb. mass/cu.ft. |

| dt = | pipe inside diameter, ft. |

The implication of Sleicher's equation is that if at the pipeline inlet (which could be the discharge of a pump) the average diameter of the dispersed phase droplets is less than that given by the equation, the droplets coalesce in the pipe until the average droplet diameter grows to davg, assuming the pipe is sufficiently long to provide the required coalescence time. If on the other hand the average droplet size at the pipe inlet is larger than davg, the droplets break up in transit, the average droplet size tending towards davg.

Although Sleicher's equation does not seem to immediately apply to flow through a device such as a pump, it does point to the factors that are significant. Specifically, the equation indicates that the following parameters determine the likely average droplet size in a device:

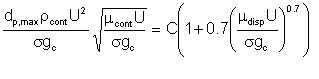

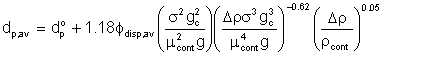

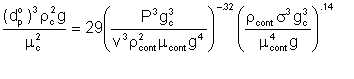

We can appreciate the relationship between energy loss and emulsification when we look at what happens in mechanical mixing with an impeller mixer. Thornton and Buoyatiotis measured the interfacial area, and hence average droplet size that resulted when organic liquids (σ' = 8.5 to 34, ρdisp = 43.1 to 56.4, μdisp = 1.18 to 1.81) dispersed in water was mechanically mixed in a baffle. They reported that the average droplet diameter was related to the fluid properties and the energy applied:

| Eqn 4/2 |

where dp° is given by

| Eqn 4/3 |

P = power for one real stage, ft. (lb. force) /hr.

v = liquid volume, cu. ft.

It has also been shown that sufficient energy could be applied to an emulsion to cause it to invert. That is, if we started with a dispersion of oil droplets in water, we could end up with water in oil, if sufficient energy is applied and provided the relative volume fractions of the phases are within a certain range. The principle of this derives from the fact that there is an upper limit to the volume fraction of dispersed liquid that can be maintained in an agitated dispersion. Quinn and Sigloh showed that for dispersions of organic liquids in water, this maximum volume fraction is given by

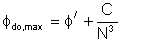

| Eqn 4/4 |

where

| φd = | volume fraction of the dispersed phase |

| N = | impeller speed, rev/hr |

| φ' = | a constant, asymptotic value |

| C = | a constant dependent on system physical properties and geometry. |

By inspection of this equation, we see that the dispersion can invert by increasing the impeller speed. Quinn and Sigloh found that with systems of low interfacial tension (σ' = 2 to 3 dynes/cm), φd as high as 0.8 can be maintained. On the role of viscosity in this phenomenon, Selker and Sleicher viewed that only the viscosity ratio is important. A further finding is that it is possible to have dual emulsions in which the continuous phase exists as droplets within larger droplets of the dispersed phase.