![Indigo Prime [title]](indigolo.gif)

by John Smith

![Indigo Prime [title]](indigolo.gif) |

Index | Loa in the machine | Requiem by John Smith

|

"The sceneshifters are concerned mainly with spatial events... relocation, environment modification.. that sort of thing. Very popular in parallel 43. They've been having a lot of problems with the Black Hole Terrorist Front there... " - Harry Basalt & Jerry Foundation

"The seamsters deal with time. Not much to say about them, really. Most agents find it pretty boring." - Max Winwood & Ishmael Cord

"The Imagineers have the most fun - shaping dreams, juggling archetypes, messing around in the collective unconscious... They're the ones who clean up after all the others. Spatio-temporal eventing tends to leave a lot of broken minds behind." - Lewis Rheinhart & Pearl Larkin

"We also have Moderators and psiLENSER at the moment. Contractual problems.

It's down to a couple of cowboys called Fervent and Lobe."

Killing time story was about Max Winwood and Ishmael cord on journey through time and space with one of history's most famous film.

|

Future Shock: Change of Scenery Prog 490, Oct. 1986 Art by Nik Williams

Indigo Prime

Fegredo and Brecht: How the Land Lied

Fervent & Lobe - Holiday on Ice

Killing Time

Text vibes :- Weird Vibes

|

Fervant and Lobe: Issigri Variations Progs - 642-649 (Sept. 89) Art by Mike Hadley

Winwood and Cord : Downtime

Text Story :- Requiem

Almaranda: Solstice

The Loa in the machine

|

An Indigo Prime story Illustrations by Mick Austin

by John Smith

T he tachyon MainPhaze unit went wild at exactly 03:67:12, standard continuum time. Technop Marlene Kellman was monitoring the operation when it happened, hunched over the sheetscreen like a short-sighted pianist, and at first she didn't believe it. She robbed her eyes, told herself she'd been working too long, and looked again.

'Judas,' she said. 'Judas H. Priest.'

The error was still there. A tiny yellow bar-code was flashing steadily at the edge of the contour map. No doubt about it. Something had gone wrong.

This was a tricky but routine procedure, a Koestler probability graft onto Las Vegas, parallel 17. Precogs were regular visitors at the casinos. Too much wheeling and dealing and a probability field would start to form, gathering above the Nevada desert like a thunder cloud. If the charge wasn't earthed it would build up until it reached critical mass, sending fallout across the whole of the West Coast. Rogue events. Carnivorous coincidences roaming the streets. People bumping into friends they hadn't seen in years; eventually bumping into themselves. They'd lost one reality like that already.Kellman's fingers moved over the touchpad, punching in a tracer routine, trying to narrow in on the problem. Most likely the field generators have misfired, she told herself. Then stooped.

On the semen a new menu had blinked up. Above it was a security code. Underneath, the words IMP/REALITY COLLISION.It was an interference pattern. She recognised it straight away. Someone, somewhere, was running their own probability generator. Or something very much like it. The effect was like two pebbles thrown into a pond. Waves colliding, ripples meshing with ripples. The surface of reality kicking and trembling like water coming to a boil.

Kellman activated her mouthphone and called Mr Vista. And Vista called Adam Valdez. And Valdez called in the Sceneshifters.

M ary Beth Thibidoux, fourteen years old and wise as Solomon, knew all about Mama Pentecost. Ever since she'd bumped into Jorlene Delamer, six months ago, she'd made it her business to know about her. Her sanity itself depended on it

Mary Beth was Elvis's number one fan. She had been obsessed with him since she was a child. Her home was a shrine to him; her life lived in his memory. And yet he'd been dead longer than she'd been alive. It was this inescapable truth that made debris of her life; that plagued her sleep with visions of bluejeans and guitars and grass skirts. Her one wish, her one great dream, was to meet him.

'One time, I swear, she had more than two hands. I almost screamed. Almost ripped that blindfold off and ran out into the street like a crazy woman...

But in the end, she said, it had been worth it. The hair style had given Jorlene a new lease of life. Put a spring in her step and a gleam in her eye. She'd been depressed ever since her mother's funeral two weeks ago. But now, somehow, all that had changed. The grief bad lifted, given way to something bright and gauzy. Sometimes, she'd said, why she felt as if her mother was right there beside her.

'That's why I went to Mama Pentecost in the first place.' Jorlene had glanced round then, and leaned closer, voice dropping to a whisper. 'Y'all see this here haircut? You know what Mama Pentecost said about it?'

Mary-Beth had shook her head.

'She says it'll put me in touch with my momma. That's what her haircuts do, she says. They put you in touch with the dead.'

And at first Mary-Beth had thought she'd been joking, thought she'd been pulling her leg. But a lot of things had happened since then - she'd seen signs at sunset, seen omens scribbled on the wind - and she knew now for sure that old Mama Pentecost still had the power'.

If anyone can bring the King back, she thought, she can.

Mary-Beth finished her jug of iced tea, then went back inside to change.

M engell and Voight had been partner's for just user six years, relativistically speaking. To Voight it seemed like a lot longer. She'd secretly put in for transfer every month for the last year and a half, but Vista had said he couldn't do a thing until a new vacancy came up.

'Besides', he'd told her once over coffee and apple strudel,' you make a great team.

And they bad. To start with, anyway. Eugene Mengell and Suzanne Voight, two of the sharpest Sceneshifters in the business. The Manchester Eschatan in 2014; a limited viral war on Chimchuringa Prime; the Rigel-Warpspawn alliance that devastated the Twelfth Empire. They'd got INDIGO PRIME out of more scrapes than Voight could remember. The problem wasn't the job. It was Mengell. As the years had passed she'd grown to like him less and less. It wasn't just his bad habits. ( Chewing gum and body building she could live with.) It was the way he looked at her. The way he licked his lips and cocked his bead to one side and watched her from the corner of his eye. As if she was some two-bit stripper in a seedy Texas bar.

Just because she worked with the guy didn't mean she had to sleep with him. Voight blamed it on the steroids. They'd done more than just beef up his body. They'd given him a groin that was impossible to turn off.

A battered pick-up truck rattled past and Voight - realising she'd materialised in the puddle of a road - stepped hastily back. She looked round her, trying to get her bearings.

It was just another hick town to her, the sort of place you passed through without stopping. She checked the da2disc. Parallel 17, Tennessee, USA. Control had said this was where the interference was coming from. All they had to do now was find out who was doing it and why. Then put a stop to it before anything dangerous happened.

There was a flurry of displaced air and Mengell materialised at the side of the road. He saw Voight and flashed her a smile. Gold fillings gleamed. Sunlight flicked off his oiled Elvis quiff like water.

'Hi,sweetheart. Miss me?'

She was about to say something, but stopped. There was a high mosquito whine and a field-drogue blinked into existence. It hovered motionless beside Mengell, a giant cat's eye that sucked up light.

'Looks like Control's had some more news in,' Mengell said.

Voight spoke to the drogue. 'What are we doing in Tennessee? I thought the problem was in Las Vegas?'

Mary-Beth raised a fist above the dour, ready to knock, then stopped herself suddenly. For some reason she felt near to panic. And had no idea why. Knock, she ordered herself What's wrong with you, girl? You want the King back or don't you? it a Well whatever you heard, chile, it's true. 'That an' a whole lot more. Some days Papa Legha hisself rides through this house, an' even he don't believe half the things he sees.' The woman took a step back, letting a lemon-wedge of

sunlight in past the door. Mary-Beth caught a glimpse of the hallway. Dark, narrow, black and red sashes hanging down the walls. On a low table nearby there was a pile of gravedigger's tools, a skull and crossbones set neatly on top. 'Well don't just stand there a-gawping, chile. You come on in now. We gotta gets you dressed and perfumed before you go see Mama Pentecost. hat we do,' Mengell said around a mouthful of gum 'is find ourselves a dog.'

They'd spent the last hour trying to locate the instability vortex, but without much luck. The interference was too strong swamping the Hasslinger unit with waves of white-water static At least now they had a better idea of what they were looking for. Mengell had detected an afterlife field with a wave portrait in the high nineties. Which meant they were almost certainly dealing with a high-level sosifurm. Mengell gave an admiring whistle. 'Three hundred stiffs throwing out enough energy to light up New York, and we still can't track the suckers down.' Dogs had an acute sense of smell. They could detect a yesodic charge from miles away, homing in on the rotten battery stench as if it were a Bitch on heat. If they couldn't track down the soulform themselves then they'd have to get a dog to do it for them. They followed the dirt track through the locust trees, down a scruffy grass bank towards the rumble of stalled traffic; the shriek of police sirens. Voight let the branches brush against her, enjoying the rasp of bark on skin, the smell of new sap. She'd spent the last three months holed up in an INDlGO PRIME Medbay, recovering after their last swipe-and-wipe manoeuvre. Being back in the real world made her feel alive again, back in control. They found the dog a few minutes later, a wiry black mongrel digging amongst the roots of an overturned apple tree. Mengell whistled and the dog trotted up to him, tail wagging. Voight turned to Mengell. 'I'll put us on-board,' she said. She took a deep Breath, focusing herself, narrowing her concentration. In her mind she conjured up a baroque set of algorithms, the complex mental calcus that could peel reality like an orange. The air shifted around her as the equation took shape. 'Are you ready?' Mengell flicked a strand of hair out of his eyes. 'Whenever you say, sweet thing.' She punched in the translation and the world was suddenly flooded with light. There was a moment of vertigo, as if she was caught in an avalanche, falling head-over-heels in a rushing white tide. Then blackness. They were in, aboard the dog's head, two stray thoughts flickering and twitching across the corpus callosum. She felt Mengell consolidate himself beside her. Let's get this over with quickly, he flashed to her. Voight ran out a sense-link to the dog's optic nerve and the world swam blurrily into focus around them. Once they had their bearings, she pinched a motor neuron arid started the dog walking. It had caught the scent already, had picked it out from the backdrop of wilderness and car fumes, and was homing unerringly in. Blindfolded, blind, Mary-Beth stiffened as Mama Pentecost's hands scuttled back down into her hair, brushing and teasing and cutting. She'd been here about twenty minutes now, sat in the worn leather chair, straining to pick up any detail her remaining senses could give her. The room was airless and cool. She could smell candles burning, cantaloupes gone rotten, goats, rum. Could hear the chrip of crickets, even above the snip-snip of scissors. But she couldn't her Mama Pentecost breathing. She was being stupid, of course she was, but for some reason the idea scared her. As she worked Mama Pentecost kept up a string of chatter, muttering sometimes to Mary-Beth, sometimes to herself talking about loa and v�v�rs and the gros-bon-ange. 'We gonna stir up them spirits, chile. We gonna bring the great white god back from the grave...'

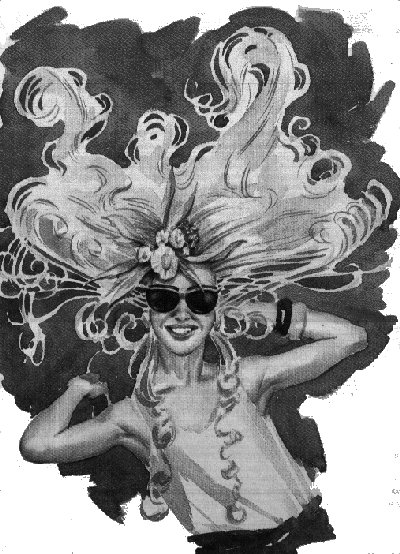

Mary-Beth's voice fluttered in her throat. 'Elvis?' 'That's the one, chile. That's him. When this hair o'yours is finished, ain't wild mules gonna keep him away.' The scissors went on snipping and Mary-Beth felt a new hair style taking shape. Dense, top-heavy. Static electricity tightened her scalp, her lips, the skin on her cheekbones. Something was trying to come through. She could feel it. A drop in temperature. The air thick with light. Mama Pentecost's voice wavered into a chant, guttural words, gibberish and the kicking in the air grew stronger. There was a sound to it now, a liquid tearing sound; and a smell, like fresh vanilla pods. Mary-Beth was afraid. She squirmed in the chair, trying to stand up, but Mama Pentecost pushed her back. A hand on each shoulder and the sound and the sound of scissors. Was that possible? How many hands did she have? 'Hold still now, girl. He's camin' through. Just got a couple more cuts to make...' But Mary-Beth wasn't listening. Her head was alive now, infested with movement. Hair prickled on her arms and neck. Her throat was sticky with the smell of vanilla. She started to struggle. Mama Penecost's hissed into her ear. 'Now you just stop that, chile. You hear me?' It was useless. Mary-Beth was on the brink of panic, a guillotine edge. She had to see. She couldn't stand the darkness another second. She reached up and snatched at the blindfold, hooking her fingers under it. More hands moved in, but it was too late, she'd already ripped the blindfold off. She stumbled to her feet, staring wildly round as her eyes adjusted to the light. There were hands on her wrists now, her arms, at her throat. As her sight wavered back Mary-Beth saw that they weren't hands at all. They were gloves. Black lace gloves floating in the air, darting towards her, clutching at her face and clothes. Mary-Beth tried to scream but there were fingers on her windpipe, choking all sound. She was frantic now, clawing and kicking, struggling wildly. But it was no good. The gloves had surrounded her, clutched every inch of her, They pushed her back into the chair, pinning her down. Somewhere behind her there was the sniggering of scissors.

fter a while the trees became sparser and gave on to a wide dusty road lined with cars. Engines growling, sunlight glinting on tinfoil fenders. The traffic jam seemed to stretch all the way to the horizon.

The dog turned its head, sniffing, and a sign wavered into

view through the car fumes: Elvis Presley Boulevard.

Hey! We're goin' to Graceland! Mengell's words were alive

in the darkness, a moving geometrical shape. Looks like we got an audience with the King. There was a moment of silence. I wonder why the stiffs came here? Mengell said. Maybe it's a place of pilgrimage for the dead, too. Voight's words thrummed. Maybe it reminds them of when they were alive.

She gave the dog another push, and it moved on until it came to a road-block. A line of police cars had been set up in front of the gate, burly sunburned officers strutting around like roosters. As the dog slunk under the barricade they caught sight of Graceland through the fence, a big ante-bellum mansion hemmed in by lawn and shrubbery. There was an unexpected spasm in the darkness. A switchblade of unease flickered through the dog's mind. It was scared. Something out there wasn't right.

I don't think this mutt wants to be here, Mengell said. We must be getting close to the soulform. She urged the dog on, feeling it grow more frightened with every step. 'the smell was near now. There was a shape to it. A taste like hot metal. Voight looked through the dog's eyes and saw they were in a graveyard.

Realisation hit like a shock of cold water.

Where?

Get us out! Mengell yelled. We're sitting ducks in here!

Voight was trying, struggling to coax the algorithm from the background chatter of thoughts. Another wave of pain and she almost lost it. Then it was there, the shape of it in her mind and they left the dog's head in a string of mathematics. The world wavered up around them as their bodies re-formed.

Mengell gave a strangled yelp, and Voight turned round in time to see a rope of ectoplasm snaked round his face. The dog lay abandoned at his feet, curled into a foetal ball, and a wall of acrid smoke momentarily blocked him from view. Mengell was yelling now, flailing at the ghosts as they billowed around him. For some reason they seemed to be interested in his hair. His Elvis quiff rippled as the spirits looped through it, ribbons of ectoplasm that seemed to be trying to knot themselves around him, parcel him up in sticky white strands. Colours flickered around Mengell's head, licked at his face, throwing up a halo of light.

And suddenly she knew why. Why Elvis, why the dead, why the morbid fascination with hair.

Years ago, while she'd still been alive, Voight had read a book called The Deviant Scalp. It was inspired by the tragic real-life story of Mimi Saunders, the legendary Hollywood hair stylist of the '20s and '30s, who'd worked her magic on stars like Valentino, Ivor Novello, Fatty Arbuckle and Sidney Greenstreet. A large number of her clients had subsequently fallen ill, wracked by headaches and nosebleeds, haunted by terrible premonitions. According to the book, Mimi Saunders had inadvertently stumbled upon on an ancient magical formula. The lost geometry of hair. The hair styles acted like tuning forks, absorbing spiritual harmonics from the aether and raising them to a higher vibratory level. The energy would pool, settle back into its past shape to form a crude ectoplasmic copy. A reflection of someone's life. A ghost.

Voight hadn't taken it seriously at the time, but now she

wasn't so sure. In fact, the more she thought about it, the

more the whole thing seemed to make a crazy kind of sense. Elvis was the butch boy king of rock and roll, western civilisation's first date. And his hair style was one of the key icons of the twentieth century. It was weighed down with values, meanings, significance. A conceptual magnet. The dead had been drawn to his grave like scrap-metal, reeled in by the promise of life-after-life, by the dynamo of charisma. A bellow of rage interrupted Voight's thoughts, and she suddenly remembered Mengell. When she turned to look she saw he'd taken the offensive. He was scooping dark time from empty air, shards of entropy glittering in his hand like flintheads. He flung them at the wraith and the spirits flew apart like rags, burning with black fire, dousing the air with a smell like liquorice. They arrowed off above the trees, back towards the soulform, white blood cells returning to base. 'Now that was weird.' Mengell swept up a hand, smoothed his hair hack into place. 'You think they'll come back?' 'It doesn't matter,' Voight said. 'We have to go after them. We have to sort this mess out before the disturbance reaches Vegas.' 'Or?' 'Or we can both forget our bonuses this year,' she said.

M

ary Beth heard the hungry snap of scissors and forced herself to sit still. She caught a glimpse of her own terrified reflection in the mirror in front of her. Lipstick smudged. Mascara running. Saw her hair said checking standing up from her head in a spindly hollow beehive, like a cage or a mitre.

Was it possible? Could it really be who she thought it was?

Mary-Beth's voice was hushed with reverence.

The figure groaned, and Mama Pentecost's laughter came floating up.

What did I tell you, chile? Didn't I say he'd come?'

It was an effort but Mary-Beth moved her eyes away from the ghost and turned back to the mirror. She seemed to spend hours searching the shadows before she could be sure she'd found her. A figure slumped in a high wicker chair, a big black woman with white hair and black She wore black gloves, a mauve and black mourning dress, a pearl necklace.

This is the house of the myst�res,' Mama Pentecost said in a reverent whisper. 'The loa pass through here like fast water.'

Mary-Beth glanced at the gloves, fingers browsing through thin air. 'What about them?' she asked. 'How they do all that?'

'It's the Gu�d�. When I cuts hair, I is ridden by Baron Samedi. He's inside me right now.'

'Baron Cimeti�re. Lord of the Cemeteries. Greatest of all the loa.' Mama Pentecost smiled. 'He's the one does all the cuttin'.'

The snicker of scissors rose in chorus, a rattle of dry laughter 'He's good with his hands, ain't he?'

Before she could reply Mary-Beth felt the gloves tighten their grip. One closed over her mouth, silencing her. Her head was wrenched savagely back, and through tears she saw Mama Pentecost lifting herself out of the chair She was holding a loop of piano-wire between boil hands. Fine as hair and razor-sharp. Mama Pentecost shuffled towards her.

The gloves moved closer, damp fingers on her face, reading her like a crowd of blind men, and for a second she lost sight of the old woman. When she saw her again the wire was falling, impossibly slow, looping round her neck tightening, slicing down through skin and bone and gristle...

Mary-Beth felt her head separate from her neck with a soft whisper of air.

For what seemed like endless minutes she was still conscious. The gloves had lifted her aloft and for a second she saw the room fully. Stone altars set against the walls, sinks filled with stagnant water. Playing cards, bottles of wine, stones in oil. A black cross wearing a top hat and a black frock-coat.

Slowly she turned her eyes towards Elvis, his ghost draped in the air like a stained sheet. His lips had parted as if he was crooning some old love song, and she imagined he was singing it just for her.

Then the blood finished draining out of her head and she died.

'W

ell, the reading's are pretty damn high,' Mengell said, checking the psi-scan, 'but I don't think it'll go critical just yet.'

Voight nodded but wasn't reassured; The soulform hung over the grave like a pall of bad weather turning with strange interior tides, soft organs in slow orbit. It hadn't made a move since Mengell's attack, and Voight was starting to feel distinctly uneasy.

A sudden thought flashed into her head. If it's not interested in us any more, perhaps it doesn't think we're a threat.

And that worried her.

INDIGO PRIME was psi-flashing them hourly updates, and it looked as if the situation was near breaking point. Probability was already starting to decay. Cause and effect to fold in on themselves. Reality was stretched to its limits. 'Okay. So what's it gonna be?' Mengell moved into view. 'What the hell are we gonna do here?'

Voight looked at him. 'I don't know. Something's wrong...'

'Wrong? What's wrong, baby, is us. They should have sent Imagineers, riot Seeneshifters. 'We're out of our depth.'

'It won't work. The time-frame would break up.'

'We've got to try something!'

She stopped abruptly. She was staring over Mengell's shoulder, her face ashen. Mengell turned to look in the same direction.

While they'd been arguing the soulform had shuddered into motion again. Its insides blurred with turbulence. The spirits were writhing like a pit of snakes, spiralling down to the ground then up through each other in crazy orbits. As they rose they polled ribbons of darkness after them, like needles polling thread.

'You were right,' Mengell said quietly. 'You were right all along.

They're building a spirit engine.

The movement looked like some alien feeding pattern. The ghosts would dip, sucking the ground dry of ore, then rise again, hauling a column of hot metal behind them. A shape was forming within the soulform, blossoming, unfurling, branching out. It was like watching a foetus fast-forward into a child.

The shape became clearer every second. A giant conch, delicately whorled. Its upper half thrusted up puzzle-blocks, spirals, levitating spheres. Voight felt an involuntary shudder of recognition.

And on the heels of that, fear. 'That isn't just a spirit engine.' The words were dead in her mouth. 'It's a von Neumann machine.' Mengell stared at tier. 'It... it can't be. These people haven'? got the technology,' he stammered, but as he watched the soulform gave birth, Voight saw recognition in his eyes, too. A von Neumann machine was a machine that could reproduce. That could breed. It divided by binary fission, like a living cell, doubling with each generation. Two, four, eight, sixteen, thirty-two... until they numbered in their millions. They could overtake a reality with frightening speed. Voight had seen it happen. Three years ago. Watched the Lokkkh hordes overrun Parallel 42 like a plague of locusts. It was a terrible sight. She bad never wanted to see anything like that again. And now here it was, happening right in front of her eyes.

M

ama Pentecost brushed cornflour from her hands, then straightened up. It was done. The libations had been made the sacrifice offered. She picked up Mary Beth severed head and placed it in the middle of the v�v�r, drawn on the floor in flour. Then she started singing

Atib�-Legha, l'uvri bay� pu mw�, agn�!

Papa-Legha, l'uvri bay� pu mw�!

Elvis's spirit was like a flag in the wind, snatched and ripped at by the forces that were gathering in the room. He shivered in a delirium of pain, and the loa shivered with him. The v�v�r was bright with power, a neon sign in the dust. Its light rose and fell with Mama Pentecost's voice.

'The spirits are gathered, Baron Samedi. Your brother an' sisters are hungry for the world. We's ready to open the gates.'

She was sat in the v�v�r now, her legs tucked under her, nursing Mary-Beth's head in her lap. Her skirt and sleeves fluttered as the loa pressed in, trying to get close.

All she had to do now was go to the cemetery. Once Elvis's spirit had joined the others the ritual would be complete; the doors would open. And, with Papa Legha's blessing, the loa would be given flesh so that they might walk abroad in the world like men.

'Take ore there now, Papa Legha.' The words were a whisper, a plea, a declaration of love. 'Take me to the graveyard. Carry me there on the back of the wind...'

Mama Pentecost was folded through space like an origami flower.

'Something's coming through,' Mengell said, and pointed.

The spirit engine steamed and sizzled on the grass, so green it was almost black. Beside it the air was sluiced with pale blue light, rolling and strobing with tell-tale static.

'It doesn't look good.' Mengell glanced at Voight. 'What are we gonna do?'

'We need a stasis field. And quick.'

Whatever was coming through she was going to be ready for it. Equations slipped through her mind, took hold of the air. A force:shield blinked up around them, enclosed them both in a protective bubble.

The blue light was already unfolding its burden black woman dressed as if for a funeral. She held a head in front of her, and at her side another spirit like a candle-flame.

'Oh Judas. Will you took at that?' Mengell let out a low moan. 'It's him, isn't it? It's Elvis? They brought the King back from the goddamn grave...

He was right. Voight sow it now, the spirit's shape. Cocked hips; quiff; pout. And it wasn't alone, she saw now. The air was alive with energy, not spirits but thought-forms, struggling to pull themselves in the real world. Voight watched them sputter against the force:shield. She could hear their voices, whispered words, a litany of names.

Agw�-taroyo.

Boron la Croix.

Damballab-w�do.

Marinette-bwa-ch�ch.

Voight felt a cold flush of fear. She knew the names; had learned them at school in New Guinea. They were the names of the loa. Voodoo gods. Angels of the afterworld.

The old woman had conjured up the Old Ones.

Elvis; the dead; the spirit engine; the swarm of loa. Knew what the old woman intended to do.

Now she's trying to let them back in...'

The old woman had finally noticed them. and her face broke into a thin smile. She seemed totally unconcerned I their presence.

'Well now. What've we got here?'

Voight moved her lips but no words came out.

'I'm Mama Pentecost. If you folk's here to try an' stop me, then I's afraid you're outta luck.' She gestured at the spirit beside her 'This here's Elvis. He's the last piece the puzzle. He's the one that's gonna start up the machine...'

Even as she watched the process was gathering speed. The Elvis ghost had slipped into the spirit engine, lighting it up like a high-watt bulb. Gears were grinding; shutters snapping like dentures. Somehow Elvis had set the system in motion.

Requiem another Indigo Prime Text Story

And of course she did. She lived her life for Elvis now that his had gone, as if She could carry part of him on. To her - to thousands like her - he was immortal, kept alive by memory and devotion. Why should she feel shame at what she was about to do? What was so wrong with bringing him back from the grave?

The National Enquirer would have a field day if they knew what I was doing, she thought, and almost laughed herself silly. The panic dropped away and she turned back to the door and knocked. A pause. Knocked again.

A hesitant shuffling from somewbere inside and the door was opened by a tiny black woman in a red cotton dress. She had a scarf in her hair and moved quickly, like a small bird. The woman squinted up at Mary-Beth,

shielding her eyes from the sun.

'You the one, chile?'

Mary-Beth stared.

'You here to make a collect-call to Elvis. That right?' She

cackled to herself, showing a brown rind of gum.

Mary-Beth nodded dumbly.

'You know anythin' about ole Mama Pentecost?'

Mary-Beth's voice was thin and quiet and dry. 'Well, I...I heard things, sure...'

That was when he'd suggested the dog.

They didn't know it yet, but it was taking them to Graceland

A

A graveyard. The Presley family plot. This was where the dead people had gathered. She almost laughed at Low obvious it all was.

What's that? Mengell asked sharply.

On the right. Just above the trees. Looks like something on fire...

Voight turned the dog's head and the sight swivelled into view. Past the shrubs and headstones the air was alive with force. A snowstorm, a rainbow, a thunderhead feverish with black lightning.

I think we've found the soulform, she muttered slowly'

That was when they struck.

She heard them before she saw them. A nasal harpsichord twang; the rasp of rusty hinges. Then they were there, the dead people, a dozen of them diving like ospreys.

They've seen us! she tried to shout, but it was too late. There was a fusillade of coppery pain as the spirits hit.

They snapped up mouthfuls of flesh, and sent the dog spinning off its feet.

'What the hell are they doin' to me?' he screamed 'They've got hold of my hair!'

Worse, something was starting to happen. The air had darkened around her head, grown tender as a bruise. It split audibly, a ghastly tearing sound, and a thick luminous fluid began to seep out of empty space. Mary-Beth watched in silence as it took shape. Streaming out, splitting off, the shadow of a barium meal. Spine opening like a fern, ribcage arching up, ectoplasmic flesh draped over bones. A wedge of quiff; thrusting pelvis; that familiar sneer...

'Is.. is that you?'

'QOM gates.' Voight's eyes glittered crazily. 'We use Mobius buicks to seal

the area, then put up QOM gates...'

She turned to Mengell, pale and sweating. 'We've got to get out of here,' she said.

'What are you talkin' about? It's just a hunch of damn stiffs...'

Voight was almost hysterical. 'Look at the head! The head she's holding! Look at its hair

'So it wasn't rut by Vidal Sassoon. So what?'

'You don't understand.' She was struggling to find the right words. 'The hair, the way its cut... It's a v�v�r. A magical symbol. it's the sign of Papa Legha.'

Mengell looked blank.

'Papa Legba. Master of Crossroads. She was babbling now, almost incoherent. 'They're trying to open the gates. The ma have been locked out of the world for centuries.

Back to main page