Wednesday 8 April

1998

Nick Auf der Maur

dies

JAMES MENNIE

The Gazette

ADRIAN LUNNY /

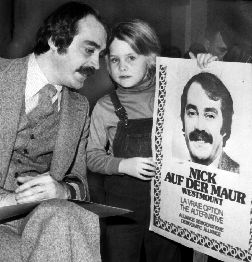

Nick Auf der Maur, with daughter Melissa, ran

in a 1976 provincial election for Democratic

Alliance. ADRIAN LUNNY /

Nick Auf der Maur, with daughter Melissa, ran

in a 1976 provincial election for Democratic

Alliance.

|

"About 30 years ago, when I

was having a merrily irresponsible time working as a

waiter in a downtown restaurant, my mother became

worried about what I was going to be when - and if

ever - I grew up.

'A writer, Ma,' I would tell her,

'I'm going to be a writer.'"

- Nick Auf der Maur column,

Dec. 15, 1993

He lived well.

Nick Auf der Maur, journalist,

politician, raconteur and the man who for 30 years

was the quintessence of Montreal died last night

after a 16-month battle with cancer.

He would have been 56 years old

this Friday.

He passed away at his home in

downtown Montreal yesterday evening. His daughter,

Melissa, and friends were with him.

"We'll miss him, he's one of

the great characters in the city and one of the best

storytellers I knew, as raconteur, sitting at a bar,

or at a typewriter," said Gazette editor in

chief Alan Allnut.

"And he was a very

compassionate guy."

Nick loved his daughter Melissa,

politics, Montreal, Donald Duck, bars, being

outrageous, and the municipal district of Peter

McGill.

He also loved a good story,

especially if he got to tell it.

Nick's hats - two Borsalinos, a

Colombian fedora, a summer panama, and a gray

"Dick Tracy" - became something of a

trademark, as did a grenadier moustache and his

ability to run city business and write a newspaper

column out of a briefcase propped up on a bar.

He became this city's unofficial

ambassador to the world, the man out-of-town

reporters would call, meet up with in a downtown bar

and interview to get a crash course on how to

navigate this city's maze of politics and clashing

cultures. A visitor's then being shown where to get a

drink after 3 a.m. was just Nick's idea of proper

diplomacy.

But in the end, the hats, the

barside politics and anecdotes produced at the drop

of a cocktail coaster were just props were for the

live version of his performance, a one-man show for

tourists willing to put up with a haze of cigarette

smoke and a three-drink minimum to find out what Jean

Drapeau was really like.

The Nick Auf der Maur most people

knew, was, despite all of the colour that dashed

through his life, a creature of black and white, a

newspaper feature we never met except through a sheet

of newsprint over breakfast. It didn't matter if we

were drinking coffee, we were drinking it with Nick.

It was happy hour.

He drank and smoked too much and

sometimes - usually a few minutes before last call -

could be as opinionated and irritating as any other

saloon regular.

But he was also a born storyteller

lucky enough to have lived a life that was itself

something of a roman fleuve, seen this city at its

finest and at its worst and write it all down for the

rest of us.

He started doing it as a reporter

with this newspaper 30 years ago and then as a

columnist with the Montreal Star, the short-lived

Montreal Daily News and, finally, back with The

Gazette.

His charm - and when he wanted to,

he could have talked the devil out of his pitchfork -

was such that others would tell their stories to him,

and somehow he could share those stories in way that

didn't make them seem second-hand. That charm also

served Nick well in a less-professional context, and

while he may have been a regular fixture at Woody's

or Grumpy's pubs on Bishop St., he also seemed

inevitably accompanied by a different and usually

strikingly beautiful female on each visit.

Many people outside of the

newspaper business - and not a few within it -

disapproved of Nick's apparently lackadaisical

approach to his work as a columnist and a city

councillor.

But somehow he managed to do both -

and do them well - for nearly a third of a century.

Perhaps his professional longevity

can be best explained by an observation made by a

friend during one of Nick's election campaigns for

city council: "Half the people in his district

share Nick's lifestyle. The other half wish they

did."

He was born on April 10, 1942, the

youngest of the four children of J. Severn and

Theresa Auf der Maur, immigrants from Switzerland who

had come to Canada to explore Severn's conviction a

fortune could be made in mining. They arrived in

Canada a few months before the great stock-market

crash of 1929. Nick would recall later that his

father would confide to him that "Swiss timing

was not my forte."

Nick recalled that he was named

after St. Nicholas von Flue, a 14th-century Swiss

patriot canonized in 1947 - a ancestor he described

as "the real St. Nick."

Nick grew up in the neighbourhood

around St. Urbain St., and remembered a childhood

that was spartan, if not poor, one where Santa once

left a note in handwriting remarkably similar to his

brother Frank's promising to deliver presents during

his next visit during the Epiphany.

Thanks to a government grant paid

to him for compulsory service as a military cadet,

Nick was able to cover the $4 monthly tuition to

attend D'Arcy McGee High School, an experience that

would allow him to later boast of exploits on the

football field, recall his first kiss and establish

an enduring friendship with a fellow student named

Michael Sarrazin.

Sarrazin would eventually be

expelled from D'Arcy McGee and go on to a movie

career. Nick would drop a water bomb on one of the

Christian Brothers and eventually get first newspaper

job with The Gazette.

At the age of 18 and after a brief

attempt at an office career with the Sun Life

Insurance Co. (he would claim he was fired after a

month for getting on top of a desk to recite a poem),

Nick travelled to Europe, winding up predictably in

Geneva where he worked as a milkman and, much to his

surprise, discovering he had inadvertently dodged his

mandatory military service in the Swiss army. He way

he told it, he fled to Greece with a female companion

and, nearly two decades later, received a retroactive

discharge from the Swiss military from the Swiss

counsel in Montreal.

Nick's career in newspapers began

with The Gazette in 1964 as copyboy making $35 a

week.

He would be arrested his first week

on the job (the charge, over the passage of time,

forgotten, but the cause of the arrest believed to

have been linked to late night reveling) and bailed

out by a local night club owner.

Nick made good his debt to his

benefactor by managing to write a positive rock

review of an act playing at the club. He was not

discouraged by the fact the knew nothing of rock and

roll or critical writing.

The review would provide Nick with

his first byline. The band in question, Frank Zappa

and the Mothers of Invention, would return to

Montreal from time to time.

Nick eventually became a reporter

and covered Expo '67, where his diplomatic duties for

wave after wave of visiting foreign reporters would

be honed. A year later he was covering the efforts of

a disgruntled provincial Liberal named Rene Levesque

to form a political party called the Mouvement

Souverainete Association.

He also found himself a part of the

wave of radical dissent that was sweeping North

America during the late 1960s.

"The bunch of us had thrown in

our lot with something called the Mouvement de

liberation de taxi, a group dedicated to ridding the

airport of its Murray Hill limousine monopoly. In

those days, we here in Montreal were always looking

for suitable working-class issues, as opposed to the

''student'' issues that seemed to dominate left-wing

American politics.

"It seems that all it took

back then to organize a full-scale riot in Montreal

was a suggestion, and lots of beer."

- Sept. 16, 1987

In 1969, however, Nick left

newspapering for the CBC, an association that would

lead to his meeting Toronto native Les Nirenberg and

their collaborating on television program entitled

"Quelque Show."

At about the same time he would

find himself editing the Quebec edition of a

politically radical magazine called The Last Post, a

publication he would later recall as a publication

for "left-wing muckraking."

It was during this period that Nick

accumulated a series of flamboyant anecdotes,

international in their scope, including a trip of

Moammar Khaddafi's Libya a visit that included a stay

in a hotel apparently full of professional terrorists

and which he described as making him feel as if

"I was in the middle of pyromaniac's

convention."

However Nick's association with the

political left, a relationship he would later admit

he cultivated in an effort to merely to meet women,

wound up providing him with what would be - for a

non-francophone - the anecdotal equivalent of the

Medal of Honor.

"It started on Monday, Oct. 5,

1970, with the kidnapping of British trade

commissioner Richard Cross by members of the Front de

Liberation du Quebec, a terrorist organization that

had been around in one form or another since 1963.

"The authorities rebuffed the

FLQ's demands. So another group (they called

themselves cells) kidnapped Quebec Labor Minister

Pierre Laporte a week later. And then on Oct. 16, the

federal government, acting on what it said were

requests from both the Quebec government and the city

of Montreal, invoked the War Measures Act and

arrested about 495 people, none of whom had anything

to do with the kidnappings but were for the most part

agitators, troublemakers, bigmouths and so on. That,

of course, included me."

- Sept. 20, 1995

Nick's incarceration was not the

stuff of romantic legend. He was held in a cell

across from that occupied by Gerald Godin, who would

go on to become a Parti Quebecois cabinet minister.

And his stay at the Parthenais St. detention centre

would be highlighted by the receipt of a car package

from his mother that included a Montreal Canadiens

hockey sweater and a prayer book.

Nick was released and continued to

rake muck. But on March 17, 1971, an event occurred

in his life that would steady if not straighten its

course.

Melissa, a daughter whose progress

to adulthood readers would follow for more than 15

years, was born to Nick and Linda Gaboriau.

By the time she had turned three,

her father had gone into politics.

"It can become easy for a

politician to develop a slightly detached view, a

thick hide, and see things in a depersonalized way.

It's a knack I haven't quite mastered."

- Sept. 5, 1984

In 1974 Nick founded with Bob

Keaton what they hoped would be a political party to

challenge Mayor Jean Drapeau's iron authority at city

hall.

To everyone's surprise, not the

least Drapeau's, the Montreal Citizens' Movement

elected 13 councillors to city hall, including Nick,

who added to the general sense of euphoria by beating

John Lynch-Staunton, the mayor's right hand man.

But within two years and displaying

an indifference to party affiliation that would

become a hallmark of his political career, Nick left

the MCM and founded a provincial party - the

Democratic Alliance - created in time to challenge

Robert Bourassa's Liberals in the 1976 election.

Running in Westmount against a

hastily recruited Liberal candidate - George

Springate - Nick was defeated.

But if 1976 was unrewarding for

Nick politically (a complaint the defeated Liberal

government could share as Levesque's PQ took the

reins of power) his profile was raised by the

publication that year of "The Billion Dollar

Games" a quickly produced and vitriolic

assessment of cost overruns for Montreal's Olympics.

The book would be credited with the eventual creation

of a provincial inquiry into the Olympian debt

Montrealers would end up spending two decades trying

to pay off.

Within two years, and running under

the banner of the Municipal Action Group (another

party he co-created), Nick was re-elected to city

hall, becoming along with the MCM's Michael Fainstat

the opposition to Drapeau's Civic Party.

In 1980, Nick took a break from

city politics to sit as president for the No

committee in that year's referendum campaign in the

riding of St. Anne.

He would be re-elected to city

council - again as a member of MAG - during the 1982

MCM election victory.

But once again, he would leave city

politics two years later to run in yet another

election - this time federal - as a Conservative

candidate on Brian Mulroney's slate. Pitted against

Liberal incumbent Warren Allmand in the west end

riding of Notre Dame de Grace, Nick would lose by

3,000 votes and earn the dubious distinction of not

being part of that year's Tory landslide.

On Sept. 14, 1986 - two months

before his attempt at another term at city hall as an

independent candidate, Nick was arrested for

obstructing a peace officer after he is found in an

after hours bar on Lincoln St. The arrest seems to

place his re-election chances in doubt, but by the

time the votes are counted, he was been re-elected by

48 votes, a victory attributed to the congregation of

Grey Nuns who voted for him en bloc.

Three months later, the obstruction

charge is dismissed because of a lack of evidence.

As an independent candidate, Nick

opposed the MCM's controversial purchase of a

$300,000 piano and was the only councillor to vote

against changing the name of Dorchester Blvd. to Rene

Levesque Blvd.

In August of 1988, even the most

jaded observer of Nick's acrobatic to political

affiliation were shocked when he announced he had

decided to join the Civic Party - the same Civic

Party whose policies had prompted him 14 years

earlier to enter politics as an opposition candidate.

It was however, a romance that was

not destined to last. By November of 1989, after

months of not so private feuding with the party

establishment, Nick was expelled from the Civic

Party, a move he said was deliberately taken to

pre-empt his announcement he would resign.

Four days later, Nick would join

the Montreal Municipal Party, a jump that would

eventually leave him leader of the official

opposition at city hall.

In 1990, and despite rumors he had

spent more time at his favourite downtown watering

holes than campaigning, Nick defeated former MCM

colleague Arnold Bennett by 300 votes in Peter

McGill.

There was talk at the time of

Nick's apparent invulnerability in the downtown core.

But it was talk that had a nervous edge.

Eventually, Nick and the Montreal

Municipal Party would sour on each other and by 1992

he was sitting once again as a member for the Civic

Party.

It would be his last term as

councillor for the district.

"For some people, birthdays

are dates of dread. Some people fall into morose

depression as they contemplate their 30th birthday,

figuring it's all downhill from there...Well, as you

get older you realize those 30-year-old punks don't

understand anything at all. The 40th is the big one.

And then you hit 40, and it comes to you that really

the 50th is the important one...And I suppose when I

hit 50, I'll realize that it's the 60th, or the 65th

or maybe the 80th that really counts.

" Maybe by that time I'll have

reached such maturity and wisdom to realize birthdays

don't matter at all, that it's not the age of the

body that counts but the state of the spirit."

- Sept. 28, 1987.

On April 10, 1992, Nick turned 50

and was feted at a downtown restaurant by a galaxy of

political and media colleagues. Prime Minister Brian

Mulroney sent a telegram of congratulations,

explaining his attendance at the affair might cost

him what little reputation he had left. Robert

Bourassa, then premier of Quebec, also sent a

telegrammed tribute, rounding out an evening

highlighted by an apparently unprovoked display of

yodeling by Nick's mother.

In October of 1993, infighting

among the members of the Civic Party's executive led

to Nick's resigning from the party to sit as an

independent. In the ensuing 11 months, Nick enjoyed a

brief flirtation with a stillborn political party

called Action Montreal, but by the time Pierre

Bourque's Vision Montreal party prepared to do battle

at the polls in November of 1994, Nick was running as

an independent, running alone.

After he was defeated, after it had

been determined that the Grey Nuns who had helped him

hang on to office eight years earlier had turned

their backs on him, Nick grudgingly acknowledged that

dismissing a group of north end constituents who had

sought annexation to Westmount as "bourgeois

slime" might have had an effect on his political

chances.

He told a reporter the night of his

defeat that he would not be moving to Toronto - but

he was out of politics.

Nick returned to writing a

freelance column for The Gazette and watching amazed

as his daughter achieved fame and fortune as bass

guitar player for Hole, the band fronted by Courtney

Love.

And then, in December of 1996,

after experiencing a pain in his neck he attributed

to a pulled muscle, Nick went to see his doctor and

learned he had throat cancer.

It was Christmas Eve.

"Last year, I wrote about the

cancer forcing me to confront my own mortality. In

these circumstances, you are left no option.

But that doesn't mean sitting

around feeling miserable and sorry for yourself.

"Sure, I go through a lot of

introspection. When I lie down for a nap or for the

night, waiting for sleep to claim me, thoughts race

through my head. I sometimes sense the damp, humid

presence of death.

"But my morale is such that I

am not intimidated. This is partly because I've had

an exceptionally good time in my life, did just about

everything I wanted. I don't in any way feel

cheated."

- Dec. 28, 1997

As with just about everything else

in his life, Nick's illness found its way into his

column. But somehow, despite the grimness of the

subject, of fighting a disease painfully familiar to

many of his readers, Nick somehow managed to bring

his own set of rules to that fight, to face eternity

rather in the same way someone might expect a bar

bill at the end of a very long, very entertaining

evening.

Nick's battle with cancer was the

one story he never got to finish, the column he never

wrote. Instead, it's a story that will completed by

hundreds of friends, some great, some decidedly less

so, who will recall their particular version of a man

who was not so much a part of this city as he was

someone who made this city a part of himself.

For those of us who knew him as a

friends, a colleague or simply the guy to phone when

you wanted to know what Jean Drapeau was really like,

there are a thousand little details that will be

retained long after the official eulogies have been

said, after the it has finally sunk in that this

truly was the last call.

Nick never wrote his memoires, he

was simply too busy gathering material for them. But

the blueprint of his life can be found in a black and

white memorial he spent two decades building.

Because in the end, Nick Auf der

Maur loved a good story.

Especially if he got to tell it.

"I've changed newspapers,

which journalists are allowed to do. I've changed

political parties. The reasons were always different,

but I always felt I was doing the right thing. Maybe

I was wrong, but I believed them to be the right

things to do. Most of all, I believe - and this, of

course, might seem terribly immodest - that I served

both journalism and politics well. In short, I like

to believe I did my duty."

- Nov. 9, 1994

|