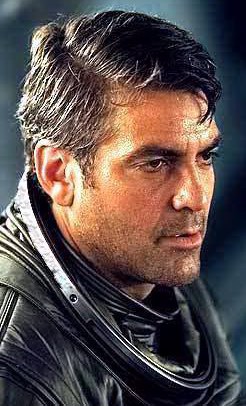

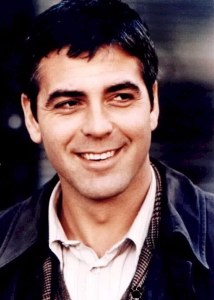

Again, with 20% more existential grief...Visiting London to promote their new film, the existential sci-fi love story Solaris, Steven Soderbergh and George Clooney were onstage at the NFT for a Guardian interview on February 13. What follows is a complete transcript

|

The Guardian UK

Geoff Andrew

2/13/03

Geoff Andrew: Back in 1989, I met a 26-year-old whose film was just about to play at the Cannes film festival. He went on to win the Palm d'Or with sex, lies and videotape. When I spoke to him around the time he made Traffic, he told me that he was going to remake Solaris. I said, "Are you crazy?" He didn't tell me who he was going to put in the film. It is a rather fine film, and one of the bravest, most audacious and intelligent films to come out of any American studio in several decades. It's not an easy film but it's really something special.

First, I'd like to thank George and Steven for coming along and doing this Guardian interview and allowing us this special screening of Solaris, which I think is quite a special film, and which I'd like to ask you about. Then I'll ask you about some of the other films you've made, and about setting up Section Eight together.

|

Let's start with Steven - you had a suggestion from a friend at Fox that you might like to make a sci-fi film and you decided to do Solaris. What exactly was the appeal of doing Solaris again?

Steven Soderbergh: Well, I guess memory was an issue that I dealt with a couple of times before and this seemed to be a very interesting way of talking about memory - having a character that was a physical manifestation of someone's memory seemed like a very intriguing idea to me. And I wasn't at all of a mind that the Tarkovsky film could be improved upon; I thought there was a very different interpretation to be had. The analogy that I use was that the Lem book, which was full of so many ideas that you could probably make a handful of films from it, was the seed, and that Tarkovsky generated a sequoia and we were sort of trying to make a little bonsai. And that was really what we were doing - I took a very specific aspect of the book and tried to expand Rheya's character and bring her up to the level of Kelvin.

|

GA: Did you feel it was risky making such a cerebral film, perhaps one of the most uncompromisingly audacious films produced by a studio in the last two or three decades. Did you ever think, oh my God, what am I doing this for?

SS: In the past couple of weeks that we've been travelling around talking about the film, there've been a lot of questions about commercial films and non-commercial films, and I've never really made that separation in my mind. There's no question that when you read a piece of material, you have ideas about how it should be realised ... certainly when I read the script for Ocean's Eleven, I thought if this was realised the way it should, then it would appeal to a lot of people. Then you get involved in a film like Solaris and if you realise it the way it should be realised, then it won't appeal to a lot of people. But what are you going to do? You have to go at it, and we've been lucky enough that Fox was supportive and let us have our way. You know, if you don't take advantage and take those opportunities to do something when things are on the upswing, then I don't know what you're doing.

|

GA (to George Clooney): Steven didn't write the part with you in mind; you wanted to be in it. It's a rather laconic role and a difficult film which is full of grief and confusion. Why did you want to do it? GA (to George Clooney): Steven didn't write the part with you in mind; you wanted to be in it. It's a rather laconic role and a difficult film which is full of grief and confusion. Why did you want to do it?George Clooney: I'm full of grief and confusion myself. There's a bunch of reasons: first, because I read the script and let's face it, you get to the position I'm in and read the amount of screenplays that I do, there aren't that many good screenplays out there. First and foremost as an actor, you want to work with a good screenplay. Then also, you feel like it's a really uncompromising film that's got to be done within a studio. We've been trying to push our involvement within the studio system, sort of push the things that we've learned from foreign and independent films through the 80s and push those things back into the studio system. Like Out of Sight isn't your standard studio film by any means; Three Kings wasn't the standard Warner Bros kind of film. And this one seemed like it was really going to push it. And I liked the idea that Steven was raising a lot of questions that he was trying to work out himself, and I thought it would really be fun to go on that run with him. You can trust a director like Steven with that kind of risk - I wouldn't have done this with some directors, who shall remain nameless.

GA: It must have been quite difficult playing so many scenes where you're not quite sure whether they're real or remembered or imagined or dreamed. How do you play that? Did Steven give you any direction ... ?

GC: No, he didn't direct. Let's face it, I did this all by myself. Um, I'd just the week before finished principal photography on Confessions [of a Dangerous Mind], which was a long hard shoot, and I'd set up an editing bay at Warner Bros and I was literally shooting on the set for 13-14 hours a day and then editing for three to four hours a night and sleeping in the trailer lot. And I thought that it would work to my advantage, the fact that I was physically tired. All you really do is show up on the set and try not to have any of those barriers, or those crutches that actors have. And with this, there were none of those crutches - there weren't that many other actors, there was no humour in it, there aren't the things that you can usually hide behind. And you just show up and let Steven say, "Okay, it's the last 13 seconds of your life - go." And trust him when he says, "Okay, now 20% more existential grief" ... So again it comes down to trust. If you're lucky enough to work with people you trust ... like I've just finished another film with the Coen brothers; you just have to trust those guys because their work has been consistently sticking their necks out, like Steven's is. And because you also know him and what he's trying to do.

|

GA: And they're even more enigmatic directors than Steven, presumably. They don't really talk to anybody apart from themselves, a lot of the time. GA: And they're even more enigmatic directors than Steven, presumably. They don't really talk to anybody apart from themselves, a lot of the time.GC: Yeah, with them, you know you're going the right way when you hear [makes honking sound]. You can literally hear them on the soundtrack, the sound of them laughing like a bunch of geese just appeared from somewhere.

GA: Steven, of course, specialises in these really heavy movies like Ocean's Eleven, Solaris and ... was the mood quite intense on the set? Because when you watch this movie, it feels pretty claustrophobic and heavy and consistent.

SS: Yeah, we had people show up with smiles on their faces that left within five minutes.

GC: We also have to explain when you're on a set where Steven's directing, it's a really easygoing place. Not just on Out of Sight or Ocean's, even Traffic. It's difficult work but there's a really professional air. It's fun - there's no yelling, there's nobody screaming, "Everybody, take your places!" So people come and visit and it's a fun place to be. This one was very different: the day we wrapped, the two of us just walked out and sat on the back of this flatbed truck and had a beer. Usually there's a celebration, but we just sat there for an hour, and everybody was like, "Yeah, see you later."

SS: I don't know if I was just tired, because this was the seventh film that we'd done back-to-back with the same crew pretty much; I don't know if it was the material. It was sort of agonising because I wanted the film to be very simple in the way that it was done and I found out the hard way that when you try to be simple, then each choice becomes incredibly important: where you put the camera, how you move the camera, how you pitch the scene ... with Ocean's, I'd be thinking there are several ways that I could do this, but with this film, I would think that there's only one way and it was incredibly difficult to figure out what this one way was. And there were many times on the set where Greg Jacobs, the assistant director who I've worked with since King of the Hill, would see that look on my face that I get like the floor has opened up in front of me, and he knows to start talking to me, when I'm sort of like somebody who's taken too much of a controlled substance, and he knows to start asking me questions to get me talking to get me out of this terror, to keep me from telling him, "Call Fox, we're stopping. I'm stuck, I don't know what to do." And more than any other film I've made, we reshot material as we were shooting - it just seemed like each of the choices was critical. I learned from Richard Lester that as your career goes on, you learn more about how things can go wrong, but you never learn how things can go right. And it's really disorienting.

|

GA: What's it like directing your business partner? [To Clooney] Do you feel that you can say, "No, I'm not doing this."

GC: We're friends, we're partners, we share the same aesthetic and we're trying to make the same kind of films. But he's a director and directors are the captains of the ship, and it's your job as the lead actor to make sure that the rest of the cast understand that by doing whatever he says. It's never a problem with Steven - everybody feels the same way. Having now directed something, I just can't imagine doing what he would do. He would go on to the set with a viewfinder, walk around and figure out how he should shoot it from how it should play. I planned everything, and I was really unfair to actors - "You gotta stand there, can't move." But Steven was like, "Well, let's see." And you would walk around and he would find a way to cover it.

GA: So the first time you worked together was in Out of Sight, which came out at quite an interesting point in your career, Steven ... GA: So the first time you worked together was in Out of Sight, which came out at quite an interesting point in your career, Steven ... GC (laughing): In both our careers. The Underneath and Batman and Robin - we were on a roll.

GA: It wasn't even The Underneath, it was actually Schizopolis and Gray's Anatomy, which were smaller than The Underneath and very much underrated. You had turned your back on commercial films and suddenly you were back with one of your most commercial films ever. Did you feel that was a real turning point for you, Out of Sight?

SS: Absolutely. It was a very conscious decision on my part to try and climb my way out of the arthouse ghetto which can be as much of a trap as making blockbuster films. And I was very aware that at that point in my career, half the business was off limits to me. And when I read the script, I thought, "I really know how to do this. I thought George, who was already attached, was the perfect person to do this part, and that it was a great opportunity for the both of us to show what we were capable of. As a result, I felt that I was under a tremendous amount of self-imposed pressure. I was very aware that if I didn't pull this off that I would be in real trouble. Then you have to go on the set, block all that out and shoot it as if you were shooting Schizopolis and you're just going off what you think's the best idea in the moment, which is just like a kind of trick in the mind. But when the alarm clock went off in the morning, my stomach would lurch. But it was a very, very important film for me, personally and professionally.

|

GA: And yet it does bear some relationship to Schizopolis and everything you've done, from sex, lies and videotape up to Solaris. You have this fragmented narrative and you're playing with film language, so it's not as if you were ever going into a different mode of film-making. You were just applying those sorts of things you do to a different sort of story.

SS: There were so many influences when I started watching films, whether it was Alain Resnais in Out of Sight or Nic Roeg - there was a scene in Out of Sight ...

GA: Nic Roeg's here tonight.

GC: I ripped him off, too, and I want to apologise right now.

SS: ... between George and Jennifer that's an actionable lift from Don't Look Now. And I've just always been fascinated by that form of storytelling. It's something that cinema does that I think truly recreates our daily experience. I mean, let's say you're walking down the street and standing on the corner, and you think about something that somebody said to you yesterday, the meeting that you have to go to tomorrow, and you're watching the Don't Walk sign to see whether or not you can cross the street. And all these things are happening simultaneously in your head. Cinema recreates that so well and so easily, so I've always

gravitated to that, even when I was young and before I started thinking about films as anything other than entertainment. gravitated to that, even when I was young and before I started thinking about films as anything other than entertainment.GA to GC: Steven's said he felt under pressure when he was making Out of Sight, what about you? You'd come out of a very successful television career, but your film career ...

GC: Was not going well, is that what you're saying?

[Laughter]

GA: Well, Return of the Killer Tomatoes was the high point...

GC: It WAS my high point, unfortunately, and still is.

|

GA: But it was as if this was the first film that seemed to know how to make use of you properly. I mean, the Tarantino film had been a lot of fun, but ...

GC: Yeah, the Tarantino film was really important to me because ... you needed to ride it when the show hit very early on, and the show was this juggernaut and arguably the most successful television show ever, and we were all on the tip of that thing and flying, and you could get quickly pigeonholed and not be able to do films. And so it was important that that first summer worked the way it did. There are things about it which were great and things which weren't, but it was important to me. See the first thing about actors is, you're just

trying to get a job; and you audition and audition and you finally get them. And you still consider yourself an auditioning actor. I auditioned for One Fine Day, I wasn't offered that. So you're still in that "hey, I'm just trying to get a job" thing. Then you get to the point where if you decide to do it, then they'll make the film. That's a different kind of responsibility, and it usually takes a couple of films to catch up. And then you have to actually pay attention to the kind of films that you're making. trying to get a job; and you audition and audition and you finally get them. And you still consider yourself an auditioning actor. I auditioned for One Fine Day, I wasn't offered that. So you're still in that "hey, I'm just trying to get a job" thing. Then you get to the point where if you decide to do it, then they'll make the film. That's a different kind of responsibility, and it usually takes a couple of films to catch up. And then you have to actually pay attention to the kind of films that you're making.[Laughter]

GC: Because as an actor, all you're looking for is a good part, and the problem is, you always think of the films as if Steven might be directing it, but the truth is, it's usually not Steven who's directing it. You got to think of things at their worst, not at their best. And Out of Sight was the first time where I had a say, and it was the first good screenplay that I'd read where I just went, "That's it." And even though it didn't do really well box office-wise - we sort of tanked again - it was a really good film. And I realised from that point on that it was strictly screenplay first. And then it becomes easier because once you eliminate the idea of doing a vehicle ... believe me, there's nobody who's encouraging us to make these films, not agents, not ... we're not getting paid for these things, and it's not like we're going to make a mint. So there's nobody out there saying, "here, go do this." So it has to be a sort of drive of your own to hammer this through, and it comes down to if you're willing to do it or not. Yeah, Out of Sight changed my career.

|

GA: Was it during the making of that film that you decided to form this company together?

SS: No, that came a little later. [To GC: ] You'd had a partner and a company already.

GC: Yeah, we were developing about 35 projects. It was one of those things where Warner Bros goes, "Hey, we'll give you this production deal, and it's already got a producer attached to it," and they put you together. It's literally like that, sort of Jerry Bruckheimer world, which works for him, but it doesn't work for the rest of the world. So he goes, "Okay, this one's called Designated Survivor. Everybody in the Senate is killed except for the one guy who's designated to go down into the basement of the White House for when the bomb goes off, and now he's president. And he's an action hero, too."

[Laughter]

GC: And I was busy working, you know. When you're shooting an hour TV series, you're busy. And I did seven films during that period: very busy. So that was what was going on, and then I'd see my name in the trades attached to some project and I'd think, "What the fuck am I doing, what is that?" And it's embarrassing. So when the deal came up, I was like, am I going to do this or not? I don't want a vanity deal. Development for an actor who's famous means that they're going to try and pitch you the same project you've been successful in. "Okay, so in this one, you're like a bat and you're a man, and you're in rubber. And then, there's like a love interest."

[Laughter]

GC: And that doesn't work. So you try to do something different, try to make films that we like. [To SS: ] You'd just finished The Limey ... and we thought, let's just go and do this.

SS: Yes, we share a similar taste and similar thoughts and a similar attitude to the business, and we thought we could get more accomplished working together rather than working on our own. And it's a director-driven company.

|

GA: Well, it's really paid off. Insomnia; next Friday we're seeing Far From Heaven with Todd Haynes. And after that, we're screening Confessions of a Dangerous Mind.

GC: Yeah, that's fine.

SS: I didn't see it.

GC: You should see it.

SS: Really?

GC: Yeah, it's fantastic.

GA: Who gets to make the decisions about which films you make?

SS: We just have one rule, which is we both have to be jumping up and down and excited about it. And that's really the only rule, and so far it's worked. If there's any sort of hesitation on the part of either one of us, then we'll just let it go. We don't know how else to do it. The good news is that George and I are not producers by day so as a result ... we got paid on Insomnia and we rolled the money into Welcome to Collinwood. So we don't have to collect a fee to keep the company going, so we're able to choose the projects that we're interested in. And in the case of Insomnia, Warner Bros had their standard list of A-directors that they were going down; I'd heard that Chris Nolan, who I'd met, really wanted to make this but couldn't get in the door at Warners. And Memento hadn't come out, so our job was to slam Chris down Warner Bros' throat and say, "This guy has a really interesting take on this material, this is the way you should go." And they agreed and said, "Why don't you guys just sort of be there with him." He's very capable and certainly didn't need our help, except in cases like he wanted Wally Pfister for his DP and he wanted Dody Dorn as editor. Warners was initially thinking, "No, we want you to have a superstar cameraman and editor, and that was an instance where we come in and go, "No, he's got to have the people he's comfortable with." And that's our job, to protect him.

GC: We get things like final cut, and we give it back to the director. Because the thing is, you still need a point of view. And that's the problem that's happening with films. A million different people get involved in it and they test the shit out of it, and then suddenly you go, "Wow, you've knocked off every edge to this thing." So our job is to protect the directors so they can make the films they want. So when it works, it works great. And we're like a tenth the cost of any of the production companies at Warner Bros because we set it up. And we've done five films in the past year and none of the others did it because we were sort of able to say, "Look, it's not going to be as expensive but it's not going to make as much money, probably."

|

GA: It's interesting, talking about helping people get the DP and editor they want. You seem to be working with Peter Andrews quite a lot on cinematography and Mary Ann Bernard, I think, the editor. Can you talk a little bit about that? [To audience] They're both Steven. How'd they get their names, especially Mary Ann ...

SS: Peter Andrews is my father's first two names. He was the one who gave me the cinema bug. He died very suddenly before Out of Sight was finished so he's missed this whole run. And so, it was just a way to kind of pay tribute to him. Mary Ann Bernard is my mother's maiden name, and I realised late in life, because I was closer to my father, that I got a lot from my mother. She's a very non-linear personality. And when I was growing up, I didn't know what to make of it and just found it kind of strange. My father was a much more linear personality, much more practical minded, and I realised when I went through that Schizopolis/Gray's Anatomy phase that led to this group of films that there were many aspects to my mother's personality that were very much a part of me and should be amplified and explored. She's someone you could never imagine holding a 9-to-5 job. She was interested in things like parapsychology and psychic surgery at a time when this was not cool. It was not on television, this was late 60s, early 70s, wife of a college professor at the University of Virginia. She was considered a kook. But she didn't care what other people thought and she just went on her own path. And I realised that I got a lot from her, that I felt the same way about my work. If you're sitting around thinking what other people think about your work, you'll just become paralysed.

GA: So you got the practical cinematographer and the non-linear editor, which pretty much sums it up. But why are you so keen to do your own cinematography and editing when you're also producing, directing and writing?

SS: I do my own driving, too.

GC: He's a control freak.

SS: No. You think?

SS: Actually, I don't really know. It's just a way to be as intimate with the film as possible. That's how I started, when I made short films, and it's a way to return to that sensation you had when you began, of making the film with your own hands. And it's a trade-off. I'm not world-class cinematographer, but the momentum and the closeness to the actors ... I'm so close to them that I can just whisper to them while we're in the middle of a take. I remember Natascha [McElhone] made a comment that she felt in the scenes that we were doing together that she was doing it with George and with another performer because I was so close and there was no one else around.

GC: We did scenes where there was not even a focus puller, it was literally just the three of us in a room. As an actor, that's a great thing, because when the director is looking at you through the eyepiece you know that he's not kind of trying to discern what you're doing from some other weird image; he's really just right there. Steven could just look up from the camera and give me a look and I would know what to do.

|

GA: This is quite different from the previous film, Ocean's Eleven, isn't it? Big cast and certainly couldn't be described as intimate. It's a lot of fun to watch, was it as fun to make? GA: This is quite different from the previous film, Ocean's Eleven, isn't it? Big cast and certainly couldn't be described as intimate. It's a lot of fun to watch, was it as fun to make?GC [laughing]: It was, for all the actors. It was the easiest shoot ever for any actor, and we all knew it when we were doing it. We were like, it's never going to be better than this. He was in hell because it was a really complicated film to put together. We were like, we're in Las Vegas, we go to work at one in the afternoon and we gotta be done by six at night. Six hours of work. Steven was editing all night.

SS: Yeah, I made it harder than it needed to be, because of this desire to get the actors in a room and see what evolves instead of trying to nail them down to some predetermined visual plan. The problem was, I had a movie that I felt demanded a fairly elaborate visual scheme and I was interested in setting up these visual patterns in terms of movements that were very layered and interconnected. There are very few repeated shots in the film. But we were shooting it out of sequence and I was making it up as I went. So it was very stressful. And it was a type of film-making that I hadn't really employed before and that's why it was interesting to me. There are certain directors: Spielberg, David Fincher, John McTiernan, who sort of see things in three dimensions, and I was watching their films and sort of breaking them down to see how they laid sequences out, and how they paid attention to things like lens length, where the eyelines were, when the camera moved, how they cut, how they led your eye from one part of the frame to another. So I was trying to break all that down and watch how they worked and recreate it in 10 minutes based on a rehearsal I'd just seen. So it was kind of stressful but I didn't know how else to do it, and the only joy came when we put it together. We showed it to Warner Bros seven days after we wrapped, and it was basically the film that was released. There was only one way to put it together and I learned a lot but my only moment of joy came during that week with [editor] Stephen Mirrione when we sort of polished the movie and showed it to the studio.

GA: Would you say that you like to set yourself challenges? You were talking about Out of Sight was a moment of pressure for you when you wanted to change your role as it were in the industry; Solaris being a difficult film in some respects, and Ocean's being another challenge.

SS: Well, I think a part of you has to be scared - it keeps you alert; otherwise you become complacent. So absolutely, I'm purposefully going after things and doing things that I'm not sure if it's going to come off or not. Certainly Full Frontal was one of those. That was pure experimentation, that's the kind of film that you make going in where you know that a lot of people are not going to like it because it's an exploration of the contract that exists between the film-maker and the audience and what happens when you violate that contract. But I felt after Ocean's Eleven, I need to do something like this, I need to go way over in the other direction or I run the risk of falling into a carved path that everybody's pushing you

|

GA [to GC]: And you've set yourself a challenge because you've now directed a film - it's an adaptation of a rather strange book; the adaptation is by Charlie Kaufman who is renowned for making such straightforward films as Being John Malkovich and Adaptation. It's a terrific first film; did you enjoy making it? GA [to GC]: And you've set yourself a challenge because you've now directed a film - it's an adaptation of a rather strange book; the adaptation is by Charlie Kaufman who is renowned for making such straightforward films as Being John Malkovich and Adaptation. It's a terrific first film; did you enjoy making it?GC: I had the time of my life, it was really fun. But that was a screenplay that was around for years, for five years at Warner Bros. Warners was never going to make the film because it didn't fit into what they could do as a studio, so they were sort of using it as bait to bring a good director in. Every good director was attached to it for a while, Fincher was and Curtis Hanson, a lot of good directors had it in their hands and were going to do it, and good actors. And so, I knew the responsibility going in was, that everyone would go, "Why the hell are you letting him do this?" So I wanted to be really prepared. I spent six months storyboarding every single shot in every scene and building transitions into each of the scenes. Some of that boxed me in later, editing-wise, but not too bad. I was able to get to fix some of the things. We had a really good time. And we came in ahead of schedule and under-budget, all the things that were important to me because I didn't want Miramax to edit the film on the floor. I didn't want them pulling pages from me; I wanted to edit it in the editing room. And it was my responsibility to come in under with other people's money so that I could get everything done. And we had hired the best people: Tom Siegel was the DP who shot Three Kings, and Steve Mirrione who's a brilliant editor was a huge impact on the film as well. Really talented, smart people came on board and it was a really fun time. I loved it.

GA: Are you interested in trying to pursue a parallel career as a director?

GC: It's an interesting thing, I didn't set out to be a director. I'm an actor and still trying to figure that out. So my reason for directing the film was that it had fallen apart, and it had had so much money against it in pre-production costs - about $5m - so it was now becoming cost prohibitive and it wasn't going to be made, period. So I made the film because I knew I could come on board and do it for scale, get everybody else to work for scale and we could make the film. I'd been looking for that, a film that I understood. You know, I grew up in live TV, my father had a gameshow when I was 10 years old which was The Money Maze, which was a giant maze and the husband would run through it and the wife would stand above it and say, "Go left! Go right!" Which seems like a perfect statement on the state of television and society at that time. So I grew up on those sets, I knew what they were like. And I understood the trappings of certain kinds of fame. And I thought it was funny, the idea that you could somehow compare bad television to the CIA just made me laugh out loud. So it seemed like if I could find something that I have an understanding of ... We've a picture that Steven wrote a draft of, called Leatherheads. It's about football in the 1920s - it's more sort of a screwball comedy so I've been watching all the Howard Hawks and Preston Sturges films, trying to understand the simplicity of that master shot and that two shot because they're so complicated, it's unbelievable. So if I can figure that one out and understand it, I could take a spin at that one. Steven has such a specific view for each film and he's going through genres, and he can go, "I can do this but I don't want to try this." I don't have that kind of understanding of film.

GA: You do have a sort of inclination towards less mainstream work; do you feel more comfortable doing that? For instance, with Batman, you've been quite open that you didn't really enjoy that. I don't think The Perfect Storm was exactly your finest moment.

GC: But each of those leads to another. I owed the studio a picture and the truth was that until Perfect Storm came out, the big knock on me was that I was not going to survive coming out of television. And the funniest thing about that is, the film made like $180m in the States and I got credit for that film opening when in fact it was about a giant wave. It was about basically CGI, but I'd taken such a hit from Batman and Robin that I didn't deserve that I was like, "Fuck it, I'll take the credit." It wasn't a very good film; it could have been but I figure, you sort of have to do one for them every once in a while. That's the deal. And I thought, if I have to do one for them, why not do one where it's six guys and they all die in the end. Honestly, at least it's not like the films that I get offered everyday. And you look at them and go, "I can't do the junket for this, I can't go do press for these films." And it brings an end to your career pretty quick, so I'm trying to find good scripts. That's what we're working on.

|

GA [to SS]: When we met in November, you said you were going to take a year off, is that correct? GA [to SS]: When we met in November, you said you were going to take a year off, is that correct?SS: Yeah.

GA: I find it hard to believe that somebody as busy - you've mentioned that you're doing two books and another little short film in the meantime anyways.

SS: Yeah. I need some time to rethink what I've been up to. I still don't feel like I'm working at level where I would like to be working. I've made some interesting movies, I don't think I've made a great movie, or a movie on a level of the films that I think of as great. I want to figure out how to step it up a little bit, so I need to clear my head for a year and see if I can figure that out. And who knows, maybe I'll never get there, but I feel that I have to make a more concentrated effort to make something ... To me the testament of a great movie is that when you see it, you just go, "I've never seen anything like this before." Just something that completely transports you. I don't know what that is but I want to try and find it, if I can. I need to just take a breather. But the one thing that I should talk about, George's film; I knew he was going to do a good job because he pays attention and he loves movies and he made a real piece of cinema. Five minutes into it, the first time I saw it, I completely forgot that it was George's movie - I was just watching a movie with actual cinematic ideas in it. He understands how to put a sequence together, and how to move from one place to another, and it wasn't, like many films made by actors the first time out, a pedestal that he erected to stand himself on top of. It's not about him, and he's only in it because that was part of the deal to get the film made. It was really fun to see him go through that process, especially in post-production, that's where the movie really comes alive.

GC: My first cut was about half an hour longer, and the first time I showed it to Steven all together, he said, "It's great, you're gonna cut, like, three of your favourite shots," and I'm like, "You're stoned, dude." About a month later, I cut those shots, which killed me, but Steven was infinitely helpful ... it's a story told from three different narratives of a guy in three different periods in his life and sort of coming to terms with the idea of having a specific one that you could really focus on and that was where he was really helpful in understanding that. It's a wild process.

GA: Yes, I think we've got Chuck Barris coming along for the interview after the screening of Confessions of a Dangerous Mind.

GC: You guys know who Chuck Barris is? Cause that's the wildest thing - Chuck's a huge star in the States.

|

GA: He's the man some might consider to be responsible for the dumbing down of television. He got very involved in devising gameshows and things. But he also claims to be a CIA assassin.

GC: He wrote a book that basically said that while he was creating The Dating Game and The Newlywed Game, he killed 33 people.

[Laughter]

GA: Anyway, you can see it for yourselves but meanwhile, you can also ask some questions.

Q1: My question is about a project called Gates of Fire which is based on a book? I know that you've been associated with it as producer ...

GC: Pressfield's book? Yeah, for a long time. We acquired the book before Steven and I were in the company. It was the one film that we held on to when I changed companies. It'll be a hell of a film - it'll cost $170m to make, and Michael Mann's attached, he's working on the screenplay. He'll call every once in a while and go, "I think there should be a battle at sea," which is like another $70m. And Rome burns, you know? And the question is, whether or not they find a practical way to make the film. We'd had it for six or seven years when Gladiator came out and sort of stole the thunder. I hope it will be made and I hope that Michael makes

Q1a: I definitely think you should play Xeo in that.

GC: You think? I want to play Xerxes. I want to be the king of Persia, cause I am so ready for that.

Q2: You say you're looking for a good script. I've got one here.

GC: Send it up here. I'm not slinging a bat in it, am I?

Q3: We've not seen your new film but just from the description we've just heard, it sounds like you and Steven share this craving for fragmented narratives. Where did this come from?

GC: Well, talk to Nic Roeg. Talk to the master of non-linear storytelling. Steven is sort of responsible for bringing it back and taking it to a different level and I've been watching him. And I just think it's so much more interesting. You watch The Limey and you just go, "God, I just love the way he's experimenting with time." Watch Don't Look Now.

SS: And a lot of that was coming, I'm sure Nic would agree, when the French New Wave broke. I remember reading an interview with Godard when he said a group of film-makers were present for the first screening of Hiroshima Mon Amour, and they were all just sort of staggered by what Resnais had done, they just hadn't seen anything like that before. And there was a freedom in French and British cinema of the late 50s and early 60s that somehow took a while to get to the States - it showed up in 67 or so and played out and died at the end of the 70s when auteur cinema in the US just got beaten into the ground.

GA: It was really Petulia, wasn't it, made by Richard Lester and shot by Nic Roeg.

SS: Yeah, which was an amazing film and obviously Pulp Fiction did a lot as well to bring the idea of non-linear narrative back into the mainstream. As we were talking earlier, it's easy to screw up. You find in the editing room, if there's been a lot of trial and error, what's fascinating is the connections that happen when you're rearranging things and pulling scenes out and suddenly there's a connection between two scenes that never showed a connection before. That's really exciting.

Q4: You've helped Chris Nolan develop and produce Insomnia which is based on a foreign movie. There's a rumour that you're doing an adaptation of Nine Queens, the Argentine movie. Would there be any other foreign movies that you'd like to adapt and any foreign directors that you'd like to work with?

|

SS: Nine Queens came about because the producers of the film were shopping the rights around town and we saw the film and said, "We gotta get that, we gotta get it right now" and made a very aggressive play to get the rights. Part of the reason we did it was I've been trying to find a project for several years now, for Greg Jacobs, my assistant director, who I think should be directing. I showed him the film immediately after watching it myself and he agreed that it was terrific and provided some interesting opportunities if you have the younger character Hispanic and you keep the older character white, there's a lot of interesting race issues to get into, especially if you set it in Los Angeles, which is a very segregated city. So I'm very excited about that. We're always looking for stuff that we think can benefit from being remade.

Q5: Solaris reminded me and aroused the same feelings as when I saw Kubrick's vision in 2001: A Space Odyssey. How influenced were you by that particular film?

SS: Well, the answer is everybody who's seen 2001 has been influenced by it. It's not just a watershed science-fiction film, it's a watershed piece of cinema. I think it's one of the most significant pieces of art created in the last century. What I think you gain when you watch any Kubrick film, or any Tarkovsky, any Antonioni or Bergman film, more than any specifics is just this absolute commitment to the original idea to make the film, the clarity of it, the passion. It's inspiring. With our film, we can make references to a couple of other films, whether it's 2001, Alphaville or Altered States. He had no references. Nobody had ever seen anything like that, ever. And it's a two hour 20 minute film about contact with a higher form of intelligence and there's not a single genuine human interaction in the entire film. The bravery of that, to stick to that idea, just amazes me. And so, when we were doing the film, we found a beautiful 70mm print that we screened at Warner Bros about two weeks before we started shooting Solaris. And the lights came on and basically all the crew turned to me and went, "Yeah, good luck."

[Laughter]

SS: We should have screened an Ed Wood film.

GA: 2001 was philosophical in its ambitions; yours is philosophical and human. I mean, one of the great things about Solaris is it brings up all sorts of interesting questions but at the same time, there was real warmth in the relationship between George and Natascha, and I found it a very emotionally affecting film and philosophically intriguing.

SS: Well, that was our hope. That if you were to make a film with a similar idea, which is indirect contact with some other form of intelligence, that there was a version to be made in which every human interaction was emotional. We were all envisioning a kind of flipside to that. Again, I think we've had a difficult time trying to give an audience who hasn't seen the film an idea of what the experience is, the rhythms are very unusual, the way the narrative plays out is very unusual. We previewed the film - you've heard the story of the guy who stood up at the press conference in Berlin saying, "I think your film is boring." Listen, I sat through focus groups in the US and I've heard a lot worse than that. I think he thought I was going to be shocked by that and he had no idea what we'd been through. And to try to reduce the film to a single image or a TV spot or a trailer was just extremely difficult. I don't think we solved it in the US, but at least here in Europe we've had the benefit of two months of screenings to let people discover it a little bit.

|

Q6: You were talking about focus groups, and I heard a rumour that Solaris had one of the worst ratings despite it being brilliant. How are your relations with the studio? Is there a relationship in the sequence of films that you work on, for example doing Ocean's Twelve after Solaris?

SS: There's a very direct relation for me. There were three projects that I wanted to do after my sabbatical. Ocean's was one of them. I had the idea when we were actually in Europe promoting the first one. The other one is a project called The Informant, which is based on the true story of a price-fixing scandal in the 80s, and the other is called The Good German, based on a novel by Joseph Kanon, set in Berlin between VE Day and VJ Day. The Informant and The Good German are seriously strange movies, really weird but, I hope, interesting. When Solaris tanked in the States on the heels of Full Frontal tanking, I immediately called George and said, "We're going to do Ocean's first."

[Laughter]

I can't get Warners to pay for The Informant and The Good German on the heels of these two films. I wouldn't pay for them.

GC: Warners were really happy - we sat them down and said, "Okay, we've got good news: we're going to do Ocean's Twelve," and they said, "Oh, Jesus, thank God." Then we said, "And you have to pick up the tab for The Good German and The Informant," and they went, "Okay, fine, whatever."

SS: And that's the reality of the film business - all three of them are movies that I'm excited about. There's a commercial and practical issue that you can't pretend doesn't exist.

GC: It goes back to what we're trying to do, which is do the films that we think are interesting and that people should see, within the structure of the studio system. And part of that means that we have to find some compromises that will help get it done. I don't think you can look at Solaris and think, "That's a compromise film." If the compromise is Ocean's Eleven, that's a good film and we're proud of it, so we'll do this, and happily, because entertainment's a good thing and I don't think it's something to be ashamed of. It's a balancing act, though.

Q7: I haven't read the Lem novel and it's been years since I saw the Tarkovsky film but it would seem to me that the religious metaphor was a lot more present in your film than his. I wonder was it consciously added or was it present in the book?

SS: I guess I would characterise myself as an optimistic atheist. Bearing that in mind, I did want our version to be able to withstand several different interpretations, and the film is sort of proposing the idea that each of us was created by the feeling that existed between two people, and that if you could isolate that feeling before it was acted upon, this film is basically saying that there's a possibility that we return to a place where only that feeling exists, that it has no connection to consciousness as we understand it right now. And I felt that you could look at that in any number of ways. The Lem novel and the Tarkovsky film were created in Soviet bloc countries, and you have to wonder what effect that has on an artist contemplating heavy, philosophical issues. Certainly I think our film's more optimistic than the book or the Tarkovsky film. They end similarly but in the book and the Tarkovsky film, he's not with Rheya. So that was my big change. I did want that happy ending.

|

Q8: What is your favourite film and why?

GC: I did a live television version of Fail Safe, I guess for personal reasons. The first time I saw it, it was a film which was sort of the straight version of Dr Strangelove, which I happen to think is the perfect film. Sidney Lumet directed it. As a child, you love the things you see on television, and television was what brought Fail Safe back, just like it brought It's a Wonderful Life back. It was when I was first aware of film-making. I loved the idea of talking about very difficult political and social issues in the heat of those issues. To go after the cold war and after nuclear arms, it was a ballsy thing to do. Strangelove is great and you've gotta love it, but unfortunately it came out first and you can't really do the spoof and have the straight version come out later, cause it's just death for the straight version. Henry Fonda is the president and Walter Matthau is a drum-beating Republican and it was just a beautiful film, beautifully shot. I just remember it being the first film that I was really affected by, cinematically and acting-wise, and socially, too. That was it for me. GC: I did a live television version of Fail Safe, I guess for personal reasons. The first time I saw it, it was a film which was sort of the straight version of Dr Strangelove, which I happen to think is the perfect film. Sidney Lumet directed it. As a child, you love the things you see on television, and television was what brought Fail Safe back, just like it brought It's a Wonderful Life back. It was when I was first aware of film-making. I loved the idea of talking about very difficult political and social issues in the heat of those issues. To go after the cold war and after nuclear arms, it was a ballsy thing to do. Strangelove is great and you've gotta love it, but unfortunately it came out first and you can't really do the spoof and have the straight version come out later, cause it's just death for the straight version. Henry Fonda is the president and Walter Matthau is a drum-beating Republican and it was just a beautiful film, beautifully shot. I just remember it being the first film that I was really affected by, cinematically and acting-wise, and socially, too. That was it for me.SS: The Third Man, probably. I actually wrote a thing, a few paragraphs, for the periodical Projections a few years ago about it.

GA: All about the zither, wasn't it?

SS: The zither! I actually had the pleasure a few years ago on Portobello Road, this was the first time that I'd seen a guy playing it - it was amazing. I heard the sound and I followed it. But I think that's my desert island movie.

GA: I'm afraid that's really all that we have time for. Would you please thank George and Steven.

|