Daily Dose of George Clooney

|

||

Solaris...

|

||

|

Jonathan Romney

Sight & Sound

February 2003

Steven Soderbergh's Solaris isn't so much a remake of Tarkovsky's film as an adaptation of the original novel as love story. But is it really more an enigmatic experiment..

Andrei Tarkovsky's 1972 Solaris begins with a delicately enigmatic image of fronds wafting in a stream; in the new Steven Soderbergh version the opening shot is of drops of water on a window pane. It's an image at once eerily noncommittal and matter-of-fact, telling us next to nothing about the film we're about to see, where Tarkovsky's tells us everything. In fact, you could say that the whole of Tarkovsky's poetic disquisition on mind, memory, nature and time's ebb and flow is in that first image, which returns at the close of the film, just before one of the most sublimely mysterious FX shots in film history.

|

|

Soderbergh's Solaris has no business with the elegiac nature imagery of Tarkovsky's film, nor does it have the same morose languor - where the Russian movie stretched to 165 minutes and didn't get off Earth for the first 40, Soderbergh contracts his cosmos into a spare, telegraphic hour and a half. His is not, it should be said, in any way a remake of the Tarkovsky film, but rather represents that quintessentially Hollywood trope whereby quibbles about the ins and outs of the 'remake' are wriggled out of a retouraux sources, afresh adaptation of the original Stanislaw Lem novel.

|

|

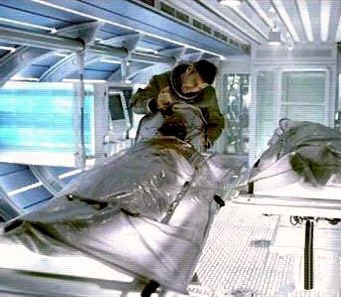

This Solaris is also, much more straightforwardly than Tarkovsky's vaulting enquiry into the state of the future soul, a love story. No more Dostoevskian colloquies here between art and science, incarnated by intense balding savants, but an intimate two-hander between a man and a woman, or rather a dead woman, or rather a dead woman's unearthly simulacrum. The man, psychologist Chris Kelvin, is played by George Clooney, whose brooding detachment for the first time acquires a real intellectual focus as he visits the space station where the influence of the planet Solaris has materialised astronauts' long-absent memories in the form of phantom 'visitors'. In Kelvin's case the planet has revived his wife Rheya (Natascha McElhone), whom he has mourned since her suicide.

|

|

McElhone, with her strangely elongated features and haunted, almost mesmerised eyes, doesnt quite have the Slavic other-worldliness of Tarkovsky's revenant heroine Hari, played by Natal'ya Bondarchuk, but she's certainly alien, in a breathily cut-glass Home Counties way that stands out as passably strange in a Hollywood context. At first, seen on Earth as the still-living, "difficult" Rheya, she seems merely arch, but in space, as she emerges out of nowhere, she comes into her own. "How are you here?" Kelvin asks. "How do you mean?" she replies, unaware anything's wrong. Her unfazed disorientation, her out-of-spaceness, plays up the film's Pirandello aspect - she's a character who's appeared in the story, unaware that she's even in a story.

|

|

The thought of a Hollywood Solaris, let alone one produced by James Cameron, might have struck dread into purist souls, but what's impressive is how committed Soderbergh is to understatement. There's a strange, telling elision, as when at one point the camera drifts past an unexplained rip in the metal wall of Kelvin's cabin. What we haven't seen - whether it was cut, or never even filmed - is Soderbergh's take on the single most dramatic image in Tarkovsky's version, the moment when a bloodied Hari bursts through a steel door. it's one of many remarkable absences that shape a film structured on discontinuities. As in the original, Soderbergh omits the space journey: Solaris might as well be next door to Earth, so suddenly does Kelvin arrive. Clooney himself is a notable absence: in the scenes where Kelvin interrogates his shipmates, Soderbergh keeps his camera away from him, as if they were simply talking into space.

|

|

Doing his own editing, Soderbergh makes this a very fragmented narrative, pausing in mid scene with fades in and out of black and providing a starkly notated vision of life on Earth at the start and end of the film. The mood approaches that of Godard or Chris Marker's futures - a whole world evoked in a few concise visual strokes, such as a bowler hat of odd design (perhaps it's another Kubrick reference, to A Clockwork Orange, supplementing the more obvious 2001 allusion in the console lights reflected in Clooney's helmet). Most of all, however, the mood is European, and not just because of the central couple's tryst in an antiquarian bookshop. The sense of temporal dislocation in tandem with romantic mourning echoes Alain Resnais' recently rediscovered Je t'aime je ta'ime (1968) while the scenes in Kelvins claustrophobically clean, sonically deadened apartment - where every shot screams Rheya's conspicuous absence have something of the soul-crushing sleekness of life in Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451 (1966). The sense of Soderbergh reviving a 1960s dream of futurism is underlined by something else we haven't seen in a sci-fi story at least since Space 1999 (1975): jackets with Nehru collars, in which Clooney looks far less ridiculous than you'd think.

The above-mentioned auteur names locate Soderbergh's film at one remove from the Hollywood sci-fi mainstream: he's pastiching 1960s art cinema's own pastiche appropriation of the genre. This might make his film appear empty and soulless to some - another, even more extreme case of Soderbergh the cold-hearted genre-snatcher borrowing a form, emptying it out and moving on. But this is to reckon without the precise, hand-crafted nature of Solaris: as his own cinematographer (under the name Peter Andrews) Soderbergh determines the total look and feel of the film, creating something that seems organic and fully formed even though its ultimate purpose may escape us. (To use a sci-fi analogy, Solaris resembles one of the Joseph Cornell knock-offs assembled in space by a rogue computer, in William Gibsons Count Zero.)

|

|

The point of the film may have been purely to see if it could be done, and if so, what would emerge - Soderbergh may simply be an experimenter in the purest sense. I cant see much connection here with any other Soderbergh film so much as with Ocean's Eleven (2001), partly because there's the aforementioned sense of a honed, autonomous machine running through its elegant but inscrutable operations, partly because that film's single most striking feature - a certain shade of blue, a little deeper and darker than the Yves Klein standard - makes a welcome reappearance here.

There is spectacle here, some of it verging on kitsch - the shifting purple patterns of the planet Solaris itself, like a deluxe version of an energy globe from Camden Market - but otherwise there's an admirably prosaic approach to standard spaceopera paraphernalia. If there must be spacesuits, then let there be spacesuits, and let them resemble the spacesuits of the past; let there be corridors, and let them be a little closer to the familiar industrial spaces of Alien (1979) than to Tarkovsky's lugubriously vacant halls. Soderbergh's real fascination is with textures and elegant details, as if to show that the accoutrements of lifestyle follow humanity even unto the depths of the galaxy: you may find yourself remembering the film for a certain metallic sheen on Clooney's pillow, or for the strange icetray edging around his bed.

|

|

Most of all, you may remember the silence. There's no music at all until Kelvin makes it into space, at which point Cliff Martinez's clipped percussion and shimmering electronica shape the mood of the film as decisively as Tarkovsky's own sound design, in which Russian voices, at once distracted and declamatory, hung in the empty, recycled air of enclosed space. Here the voices are muted like felt or suspended in relief against a gossamer steel-mesh sound. You may be thoroughly moved by Solaris, or find it elegantly pointless, yet either way there's a sense of a controlled, melancholic intellect bringing all the pieces together and letting them float: the planet Solaris, you might say, is played by Soderbergh himself.

|