Daily Dose of George Clooney!

|

||

Navigating By The Stars...The long, thrilling journey to a new Ocean's Eleven

Stephen Galloway

Las Vegas Life

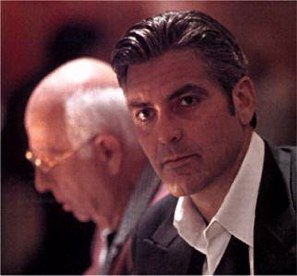

Danny Ocean (George Clooney) is a con man on a mission: Rob three casinos in one night In the spring of 1999, writer Ted Griffin was in a funk. Danny Ocean (George Clooney) is a con man on a mission: Rob three casinos in one night In the spring of 1999, writer Ted Griffin was in a funk.Sitting in his Hollywood home, he was bracing for the release of two films he’d scripted, Ravenous and Best Laid Plans—both of which he thoroughly expected to tank—when his agent called, telling him that Jerry Weintraub wanted to meet with him. Weintraub, of course, was the larger-than-life manager-turned-producer who had been a staple of upper-echelon Hollywood for almost four decades.

When they met, Weintraub had a simple proposition: What would Griffin think of reworking the 1960 Rat Pack heist picture, Ocean’s Eleven, and making it a vehicle for several major stars, but setting it in the very different world of contemporary Las Vegas?

“I knew of the film, though I’d never seen it,” Griffin recalls. “But it sounded like the sort of movie I really wanted to see, and that’s why I wanted to write it.” Ocean’s Eleven was close to Weintraub’s heart. He had been on the set of the film when it was shot with stars Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr. and Dean Martin, and he fondly remembers the shoot.

|

|||

“The guys were working the Sands at night and they were doing the film in the day,” he marvels. Stories about the troubles director Lewis Milestone had with his cast are legion, but, contrary to myth, Weintraub notes, “There were no problems. They were all buddies.”

If the project had sentimental appeal for Weintraub, it intrigued Griffin for other reasons.

“It’s the perfect thing to remake,” he says, “because it’s a little dated and it’s a little slow, and I thought it was a great chance to do one of my favorite genres—professionals on a mission, like The Great Escape and The Dirty Dozen and The Sting.”

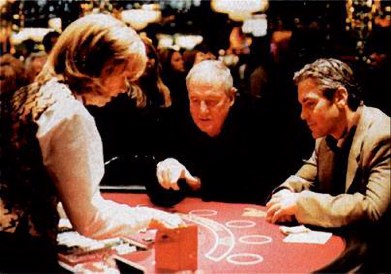

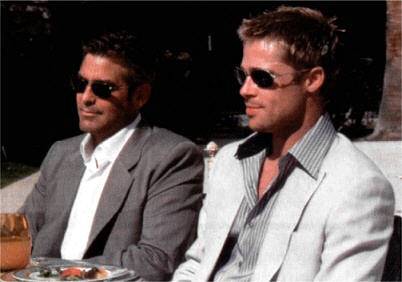

Griffin quickly set about trying to figure out how to tell the story of a casino robbery that involved not one or two characters but 11 major figures, each of which he wished to delineate in an interesting way, with each integral to the plot. As he worked, a new story—much more complicated than the original—began to come together. “The original film was about an Army unit getting back together again, leaving their workaday worlds to execute an impossible heist, which I never bought into,” Griffin says. “This film tells the story of Danny Ocean [George Clooney], a con artist and thief, who is released from prison with just the suit he wore when he came in and a wedding band and divorce papers in his pocket. He recruits his best friend, Dusty Ryan [Brad Pitt], to pull off the Everest of heists—knocking over three casinos in a single night.” Griffin quickly set about trying to figure out how to tell the story of a casino robbery that involved not one or two characters but 11 major figures, each of which he wished to delineate in an interesting way, with each integral to the plot. As he worked, a new story—much more complicated than the original—began to come together. “The original film was about an Army unit getting back together again, leaving their workaday worlds to execute an impossible heist, which I never bought into,” Griffin says. “This film tells the story of Danny Ocean [George Clooney], a con artist and thief, who is released from prison with just the suit he wore when he came in and a wedding band and divorce papers in his pocket. He recruits his best friend, Dusty Ryan [Brad Pitt], to pull off the Everest of heists—knocking over three casinos in a single night.”The thieves are bankrolled by a former casino owner (Elliott Gould). Their target is a series of casinos owned by a relative newcomer (Andy Garcia), who, to make matters interesting, is involved with Ocean’s ex-wife (Julia Roberts).

With Griffin’s screenplay completed, the picture moved forward at warp speed. Weintraub and Warner Bros.’ production chief, Lorenzo di Bonaventura, took the material to director Steven Soderbergh, who was editing Erin Brockovich. Simultaneously, they went to Soderbergh’s close friend Clooney, who was teamed with the director in a movie company they had formed after making Out of Sight together. Within days, in January 2000, both had committed to the film.

|

|||

Griffin started working with Soderbergh immediately and kept working with him as Soderbergh finished his next assignment, Traffic.

“Steven is the easiest and most demanding guy I have ever worked for,” Griffin says, “because he has a work ethic that makes you feel really horrible if you don’t match it. He works all the time: He wrapped Traffic on a Sunday in Tijuana, and we met to start working on the script over lunch on Monday in Burbank.

“The first thing Steven did was give me the script back, and he’d written SBOT—which stood for Something Better Out There—30 to 40 times on a 120-page script.” Soderbergh’s SBOT’s applied to everything from individual lines of dialogue to whole scenes.

Some of the changes were quite pragmatic: One of the characters had been conceived of as having only one arm, but Soderbergh and Griffin decided to change that when they realized the vast expense it would entail in terms of computer graphics work.

While polishing the script with Griffin—which culminated in the two locking themselves in a hotel room for five days to hammer out final changes—Soderbergh went about casting his film.

Even before his Oscar win for Traffic, Soderbergh’s reputation was strong enough that he managed to piece together the kind of star-studded cast that’s almost impossible to get for one film in today’s Hollywood, including Roberts, Garcia, Matt Damon, Carl Reiner, Don Cheadle and Gould. “I had read the script and thought there were two parts I could play,” Gould says, “and I was hoping Jerry Weintraub would reach for me.” After a dinner at Los Angeles’ Daily Grill (“I had liver with onions; he had shrimp,” Gould recalls), Soderbergh offered him the part he really wanted: the old-style casino operator laden with gold and jewels.

As casting proceeded, Soderbergh and his longtime crew began figuring out how to create Las Vegas on film. Right from the start, the filmmakers wanted to portray a very different Vegas from the original film.

“It’s 40-some years later,” Weintraub notes. “The place has changed dramatically. There were only three or four hotels back then, and they were small. Now it’s a huge city.” “It’s 40-some years later,” Weintraub notes. “The place has changed dramatically. There were only three or four hotels back then, and they were small. Now it’s a huge city.”It’s also a city that the production staff wanted to present in a positive, even glamorous, light.

“It’s about contemporary Las Vegas,” says production designer Philip Messina. “It’s not an homage to the 1950s and 1960s Vegas. We wanted the height of Vegas elegance. This was a love story to Las Vegas—we didn’t want a lot of neon, the big glitzy signs; we wanted the best of what Vegas had to offer, and we felt that was embodied by Bellagio. When you walk into that casino, it is by far the most sophisticated, well-detailed hotel. That’s what we wanted in wardrobe, sets. We upped the way everyone was dressed; we created a somewhat mythical Las Vegas.”

The exception: the home of Gould’s character, which is a throwback to an older Vegas. Ironically, that was the hardest location to find.

“We looked for a ‘modern’ 1960s home in Las Vegas,” Messina adds. “We looked for weeks on end. We ended up finding a house in Palm Springs.” By almost any standards, Ocean’s Eleven was a particularly complicated film to make. It not only meant filming in several Las Vegas casinos; it also meant locations ranging from a prison in New Jersey to a circus in Florida. It meant feeding and costuming thousands of extras; finding rooms big enough to contain the 11 members of the heist team; working around a fight at the MGM Grand; and constructing a special vault that would be a main feature of the film.

“One of the biggest problems we had was getting this large company of between 125 and 150 people around the country,” says production manager Fred Brost. “One day, we had 10,000 to 12,000 extras.” Without Weintraub’s longstanding contacts in Las Vegas, the film probably could not have been made—or, if it had, it would have cost several million dollars more than its estimated $90 million budget.

At one point, afraid that the crew might not get the cooperation it needed, Messina actually created a model for the main casino that would have cost as much as $6 million and spilled out of one of the biggest sound stages on Warner Bros.’ Burbank lot. Weintraub was never worried, though. “There was nothing that we needed or asked for that wasn’t delivered,” he says.

|

|||

Weintraub arranged a meeting with Steve Wynn, then owner of Bellagio. The very night Weintraub and Soderbergh dined with Wynn, news arrived that Bellagio had been sold to MGM. A dozen or so of the movie’s top production staff had flown to Las Vegas along with Soderbergh to meet with some of the hotel’s key executives. The meetings—still with the old management team—went well. Days after, the Ocean’s Eleven team sent a detailed memo outlining what they wanted, and Bellagio officials replied that the team could have everything they needed.

“We were given carte blanche from Bellagio, which is 95 percent of our casino floor, our home base—we were given unprecedented control,” Messina says. “I was able to build a quarter-million-dollar set on the floor of Bellagio—we cleared out slot machines and gaming machines and built a casino cage set. It was built in LA and painted in LA and trucked out to Vegas and assembled on location.”

Other hotel-casinos were just as cooperative. Staff at the MGM Grand worked in tandem with the Ocean’s Eleven crew so that a fight scene in the film could be shot around a real fight the casino was staging. That allowed the film crew to save hundreds of thousands of dollars in set and lighting costs.

Even with real Vegas locations, much work on the set remained to be done. Even with real Vegas locations, much work on the set remained to be done.“We created a bank of elevators where they didn’t exist outside Le Cirque,” Messina adds. “It was all pre-built; we installed it after they closed the night before we shot. We started putting it up at midnight, had it ready for the shoot at 7 a.m., disassembled it, and they were ready to open at 4 p.m.”

The vault the robbers break into also had to be designed from scratch, as did a long elevator shaft. “We had what was meant to be a 200-foot elevator shaft that our guys have to get past,” Messina says. “We built four separate set pieces, then the computer stitched them together. There was a lot of CGI work.”

Those and some other interiors were filmed in Los Angeles, but the bulk of the shooting took place in Vegas, beginning in February.

“One of the most difficult parts was dressing the extras,” notes costume designer Jeffrey Kurland. “In contemporary films, you usually use what the extras bring, but because we wanted a glamorous look, we had to dress most of the people. The most we had to look at was about 3,000 people for the big fight scene. We dressed 500 of them and had to look color-wise at everyone. I had a staff of 20 people collating and doing alterations.”

“For a huge movie like this—and it was huge—it was so amazingly smooth,” Kurland marvels. “It went so well, the actors all got along so well with each other, it couldn’t have been a more ideal situation.”

Even veteran crew members speak of the team’s warmth—manifested in everything from the frequent partying to the farting contest that Clooney and Pitt staged on a flight back home.

They seem in awe of Soderbergh’s passion for work—especially the night he won his Oscar for Traffic, when he returned to Las Vegas only hours after the ceremony ended, ready for a 6 a.m. shoot the next day.

“The night of the Oscars, we had a party up in a suite in Bellagio,” Griffin says. “We didn’t expect Steven to win—and he won—and we started celebrating and some of us stayed up to 1 a.m. Then we were staggering back into the Bellagio lobby, and there in the bar are Steven and [first assistant director] Greg Jacobs, still in tuxedos from the ceremony—they’d just flown back, and at Steven’s side was his black overnight bag containing the envelope Tom Cruise opened and his gold statuette! There he was, at the peak of his career, and he spent less than 45 minutes at any function after the awards, just to get back to work.”

After principal shooting wrapped in late May, there was only one significant re-shoot—for understandable reasons: “One of Ocean’s entourage is a highly skilled Chinese acrobat who is a key element of how the heist is performed,” Brost explains. “Unfortunately, on the very first day he worked, he slipped and fell and messed up his face. We had to find another acrobat.” The incident required no more than one day’s work. Another change: Following the September 11 terrorist attack, the filmmakers switched an exploding hotel from the New York-New York to a fictional resort; it was handled through computer graphics. After shooting wrapped, Soderbergh began the complicated process of editing, scoring and doing test previews of the film. A successful initial preview took place in Scottsdale, Arizona, in July, followed by another in Pasadena, California, a month later.

“The first one went really well,” Griffin recalls. “But with a few changes, the Pasadena one was inestimably better. The shocking thing is that the changes between those two versions probably amounted to only 60 seconds of cuts—and yet it had such an impact! And that’s what surprised me most in the whole process—how slight permutations can have such an effect.”

Now, Soderbergh, Griffin and their colleagues are anxiously awaiting the film’s Las Vegas premiere on December 7—at Bellagio, of course.

All the signs look good. But Griffin cannot help recalling a remark made by Soderbergh.

“He said, ‘If having a great time while making a movie translated into making a great movie, then The Cannonball Run would be the greatest movie ever made—and maybe the original Ocean’s Eleven would be, too.’”

Stephen Galloway is a former editor for the Hollywood Reporter

|

|||

|

|

|||