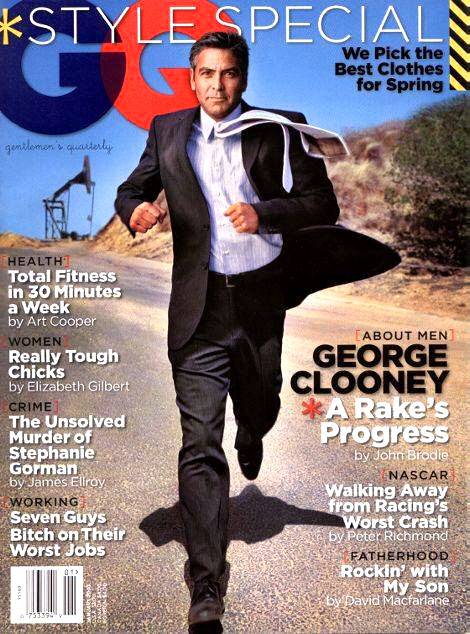

Daily Dose of George Clooney!

|

||

A Special thanks to Katie for the images and article

|

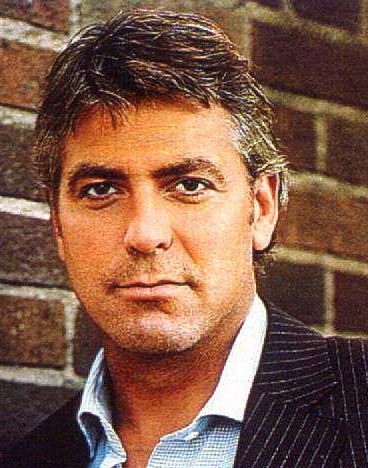

It's a warm September night in Los Angeles as three Universal Pictures executives wind their way up Laurel Canyon to a private screening room. Their mission is to watch a rough cut of Confessions of a Dangerous Mind - a biopic about Chuck Barris's double life as a game-show host/spy - then decide whether to give the film's first-time director a shot at being a second-time director. The pressure would be enough to send most rookies scurrying for their Depends, but the film's director has bigger concerns on his mind. It's a warm September night in Los Angeles as three Universal Pictures executives wind their way up Laurel Canyon to a private screening room. Their mission is to watch a rough cut of Confessions of a Dangerous Mind - a biopic about Chuck Barris's double life as a game-show host/spy - then decide whether to give the film's first-time director a shot at being a second-time director. The pressure would be enough to send most rookies scurrying for their Depends, but the film's director has bigger concerns on his mind."Bud or Miller?" asks George Clooney as he pulls open the stainless-steel door to his fridge. He entered his house only moments ago, leaving enough time to give his private screening room a quick sound check before Universal Pictures' vivacious chairwoman, Stacey Snider, arrives with her two copresidents of production. Clooney is dressed in a white T-shirt, grey chinos and work boots, and in person he's slighter and more mature than one might expect. At 41 he has nearly as much salt as pepper in his tousled hair. Peering in the fridge, he spies a Bud and grabs it. Meanwhile, two British bulldogs, Bud and Lou, slurp from water bowls. Max, his pet pig, is camped out in the vestibule, forming a giant porcine doorstop.

The house once belonged to Stevie Nicks, yet all traces of the White Witch's décor have been exorcised in favor of a Lake Tahoe-lodge scheme. Call it neo-Godfather II: wood beams and rough-hewn stone. But if Chez Corleone was a compound of intrigue and murder, Casa de Clooney (as George's friends call his sugar shack in the Hollywood Hills) is one of frivolity. Dust gathers in the dining room and living room, bu the cigar lounge - complete with a Guinness tap - and a TV room with an adjacent steam bath get the wear and tear. Two black-and-white photographs by Sid Avery, hung in the TV room, set the vibe. The first is a vintage snap of Danny Ocean and his apostles - Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Joey Bishop, et al. - lined up on the Las Vegas set; the second is of Clooney's wrecking crew on the set of the remake.

He opens the door to the patio and walks past the grotto-style pool, stopping to point out a hillside retaining wall where he has installed a miniature version of the iconic Hollywood sign. "I was dating this woman, and when her parents came to visit France, I nearly had them convinced this was the real thing," he says, alluding to his last serious relationship, with the law student Celine Balitran. It was a three-year run. "We were close in a really great way, but it was never like, OK, this should somehow come to this pinnacle where we get married." He opens the door to the patio and walks past the grotto-style pool, stopping to point out a hillside retaining wall where he has installed a miniature version of the iconic Hollywood sign. "I was dating this woman, and when her parents came to visit France, I nearly had them convinced this was the real thing," he says, alluding to his last serious relationship, with the law student Celine Balitran. It was a three-year run. "We were close in a really great way, but it was never like, OK, this should somehow come to this pinnacle where we get married."Clooney wed once - years before he became a star on ER - to Talia Balsam, the daughter of actors Joyce Van Patten and Martin Balsam. The marriage lasted three years. "I loved being married to her when things were going well. It's not that I'm against the institution of marriage. I'm just against it for me, " he says as we walk down a stone path to his guest house, adjoining a basketball court. His life is post-connubial now. In lieu of looking to a wife and children as his refuge from the world, he looks to the Boys, a group of eight pals who meet here most Sundays for a male bondathone: hoops, shvitzing, and barbecue. Most notable among their ranks are Richard Kind, of Spin City fame, and Ben Weiss, the TV director. In the guesthouse, each has his own locker with a nameplate; it's fitting - they're friends from before Clooney was famous, before friendships became transactional.

|

Clooney has accepted the solitude of the long-distance bachelor. If he were to live up to his tabloid image, he would not have enough hours in the day. Yes, it's true that nearly every actress with whom he has collaborated has broken off a relationship with another man while working with him. Yet Clooney has never been the catalyst. Drew Barrymore and Tom Green split up as she was starting work on Confessions. Julia Roberts and Benjamin Bratt parted while she was shooting Ocean's Eleven. Nicole Kidman presented Clooney with an award at the Golden Globes, and the tabloids portrayed him as the mule kicking in Tom Cruise's stall. Clooney has accepted the solitude of the long-distance bachelor. If he were to live up to his tabloid image, he would not have enough hours in the day. Yes, it's true that nearly every actress with whom he has collaborated has broken off a relationship with another man while working with him. Yet Clooney has never been the catalyst. Drew Barrymore and Tom Green split up as she was starting work on Confessions. Julia Roberts and Benjamin Bratt parted while she was shooting Ocean's Eleven. Nicole Kidman presented Clooney with an award at the Golden Globes, and the tabloids portrayed him as the mule kicking in Tom Cruise's stall."Yup, I was doing them all," Clooney deadpans. "So when I started working with Catherine Zeta-Jones on this Coen brother's movie, I asked her, "How are things going with Michael?"

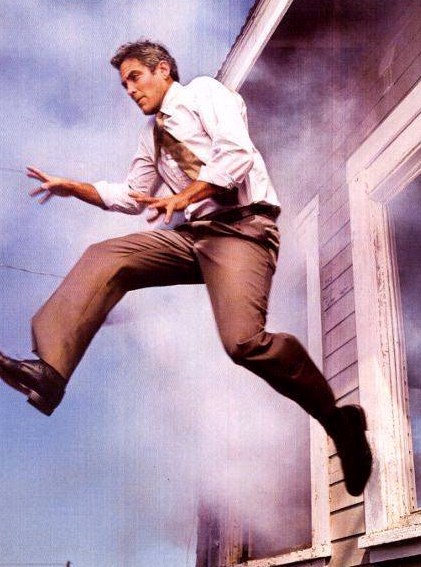

Despite the occasional paparazzi shot of Clooney lip-locked with some brick-house, he claims he's had little time for a relationship during the past few months. There were the reshoots for Solaris, his business partner Steven Soderbergh's existential sci-fi film, plus playing a Beverly Hills divorce attorney opposite Zeta-Jones's gold digger in the Coen brothers' comedy Intolerable Cruelty. All the while, he has been editing Confessions, which stars Sam Rockwell as Chuck Barris, the man who created The Dating Game and hosted The Gong Show - and allegedly moonlighted as a CIA assassin. Clooney plays his control agent at the CIA, Jim Byrd. Drew Barrymore is Barris's significant other, and Julia Roberts plays the femme fatale Barris can't resist yet should.

|

It's an unusual project, and part of the allure, Clooney says, stems from his childhood. He grew up with television, literally and figuratively. His father, Nick, worked as a local television personality in Cincinnati and Clooney spent hours on the sets. "I was a floor director on my dad's show, which was local TV. The same cameras, same size set that Chuck used on The Dating Game, so I know what that world feels like. But there were other reasons. I also understand the trappings of celebrity personally, so I thought I had some advantages there. Also, I had a real driving energy to get the movie made." It's an unusual project, and part of the allure, Clooney says, stems from his childhood. He grew up with television, literally and figuratively. His father, Nick, worked as a local television personality in Cincinnati and Clooney spent hours on the sets. "I was a floor director on my dad's show, which was local TV. The same cameras, same size set that Chuck used on The Dating Game, so I know what that world feels like. But there were other reasons. I also understand the trappings of celebrity personally, so I thought I had some advantages there. Also, I had a real driving energy to get the movie made."Which is why the Universal people are here. After serving them take-out pasta, Clooney ushers them into his screening room. It's mannish and functional: dark carpeting, several rows of brown leather armchairs. No vintage posters. Just a few jars of bite-size candy bars in an alcove opposite a door that leads to the patio where his pig sleeps in a dog house.

Like many leading men of his caliber, Clooney could have directed at any number of junctures in his career ("Tonight on Must-See TV, a very special ER …"). But as the movie begins to play, it's clear why he waited to spend his celebrity capital on making Barris's story: Surely some of it has to do with the movie's complex politics, wherein people and relationships are not always what they seem. Clooney is a liberal's liberal who believes Mario Cuomo should be our president, and he keeps a photo of Jimmy Carter's ER set visit on display in his bathroom. He also dislikes the current president. ("The problem," he told me over lunch the day before, "is we elected a manager, and we need a leader. Let's face it: Bush is just dim.")

|

Clooney was attracted to Barris because of the hay that could be made with his story. After all, here was here was a man who created some of the schlockiest TV ever and was derided for lowing the standards of decency - yet Barris says he did wet work in West Berlin for the US government. Confessions provided Clooney with a stage on which to play US Cold War statecraft as a farce. When the camera pans down a row of agents at a CIA training camp, for instance, Barris's fellow recruits include one named Oswald and another named Ruby.

The movie is peppered with such twisted touches, moments that reveal a Dr. Strangelove-like mentality at work. There's another movie to which Clooney owes a creative debt: Carnal Knowledge. The 1971 film casts a long shadow over Confessions. There is a shot, for instance, of Drew Barrymore that borrows from the way Mike Nichols held the camera on Candice Bergen while here character suffered heartbreak at the hands of Jack Nicholson. Clooney had Rockwell watch it, because, as he says, "I wanted a performance like Nicholson's. Barris could be unapologetic and unkind, but we still have to root for him." The movie is peppered with such twisted touches, moments that reveal a Dr. Strangelove-like mentality at work. There's another movie to which Clooney owes a creative debt: Carnal Knowledge. The 1971 film casts a long shadow over Confessions. There is a shot, for instance, of Drew Barrymore that borrows from the way Mike Nichols held the camera on Candice Bergen while here character suffered heartbreak at the hands of Jack Nicholson. Clooney had Rockwell watch it, because, as he says, "I wanted a performance like Nicholson's. Barris could be unapologetic and unkind, but we still have to root for him."Rockwell has his own theory as to why Clooney would be drawn to making a movie about a cad. "George understands relations between men and women, " Rockwell says. "All the traps. And he understands the dark part of Chuck, too. I don't think you can be as magnetic a leading man as George Clooney is unless you have a dark side."

Long before there was Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, the George Clooney movie, there was Chuck Barris. He's 73 now and lives in a penthouse on Manhattan's Upper East Side. Like an old jazz musician, he comes across as avuncular yet cool. His speech is peppered with dated jive - he refers to women's breasts, for example, as "big bouncy cats." His hair has gone white, and he has wire-rimmed glasses. But he still has the same glint in his eye that he had when hosting The Gong Show and introducing one of the commedia del Barris regulars such as the stagehand Gene, Gene the Dancing Machine.

|

Although Chuckie Baby can live in full anonymity today, there was a time when he wa not so fortunate. During The Gong Show's four-year run in the `70's, critics excoriated Barris as the Exxon Valdez of television. Ultimately, his thin skin got the better of him and he sold his company, moved to Saint Tropez and lived out what he calls his "F. Scott Fitzgerald fantasy" from 1987 to 1996. He also wrote the cult classic Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, equal parts therapy and memoir, which he wryly subtitled An Unauthorized Autobiography. "I was interested in this idea of how a guy could get crucified for entertaining people yet get medals for killing them," Barris says. Although Chuckie Baby can live in full anonymity today, there was a time when he wa not so fortunate. During The Gong Show's four-year run in the `70's, critics excoriated Barris as the Exxon Valdez of television. Ultimately, his thin skin got the better of him and he sold his company, moved to Saint Tropez and lived out what he calls his "F. Scott Fitzgerald fantasy" from 1987 to 1996. He also wrote the cult classic Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, equal parts therapy and memoir, which he wryly subtitled An Unauthorized Autobiography. "I was interested in this idea of how a guy could get crucified for entertaining people yet get medals for killing them," Barris says.In the book, Barris recounts how a middle-class kid from Philadelphia broke into TV. At roughly the same time he was pitching The Dating Game to ABC, he applied to and was accepted by the CIA. Just as The Dating Game begot The Newlywed Game, his assassination of a Communist in the Mexico City led to his shooting a West German labor official. By the time he left the agency during the Reagan years, Barris claims, he had killed more than thirty people. Unless Barris is a sociopath, one would have an easier time imagining Pat Sajak as the coke-snorting jefe of the Cali drug cartel than picturing the nebbish across from me plugging someone with a .38.

When I asked Clooney earlier whether he thought Barris had actually worked for the CIA, he answered, `In the book, Chuck says he killed thirty-three people. One time we talked about it, but most of the time he avoided it, and like a good defense attorney, I never pressed the point."

But today, here high atop Third Avenue, it is just Chuck and I.

"How can I confirm, prove, or disprove what you allege in the book?" I ask.

"I don't know. Go try to confirm it." is Barris's reply.

So, since Clooney cannot say and Barris will not say, that leaves only the CIA to authenticate Barris's tall tale.

"There is no record of Mr. Barris ever having had anything to do with us here," claims a government official, who called me in response to a Freedom of Information Act request I'd filed and several phone I'd placed to the Central Intelligence Agency inquiring about Barris.

"What if he was working on contract or as a freelance agent for the CIA?"

"We would have some kind of record. The notion that Mr. Barris was a contract assassin is patently absurd."

|

Even if Confessions is a Dadaist stunt, like the Unknown Comic's stand-up routines, Barris's point - that being a hit-making producer and a government hit man are equally sinful jobs - makes a certain sense. Especially for Clooney. The deeper into the movie he got, the more he made it a comment about the dangers of blind patriotism, showing how Barris the man becomes as tainted as the country he represents. Even if Confessions is a Dadaist stunt, like the Unknown Comic's stand-up routines, Barris's point - that being a hit-making producer and a government hit man are equally sinful jobs - makes a certain sense. Especially for Clooney. The deeper into the movie he got, the more he made it a comment about the dangers of blind patriotism, showing how Barris the man becomes as tainted as the country he represents.The screening has ended. The Universal executives have seen themselves out, and Clooney and I have grabbed more beers and settled in the TV room to watch Nightline. It's drums-along-the-Euphrates time, and Senator Tom Daschle is lashing out at the president for trying to stifle debate days before the congressional vote on whether or not to invade Iraq.

A Newt Gingrich comes on the screen, Clooney flaps his arms and starts making a dinosaur growl. "Look at him," he says. "Look at Gingrich. Doesn't he look like a velociraptor? He looks like a dinosaur. The man has no arms. Roarrrrr!"

Clooney comes to his politics by way of his father. He describes his old man as a free-speech advocate "who's also a 67-year-old guy who doesn't really want to hear Eminem." The definitive image he has in his head of his father is him lining up to see the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition after it had banned in Cincinnati but subsequently reopened to the public. Says Clooney, "So there's my dad in a three-piece suit standing in front of a photograph of a guy bent over with a ship in his ass, which he hates, but he's not going to be told he can't see it. That's why I adore my father."

Clooney acknowledges that stars pontificating about issues they are not well versed in can do more harm than good, but he feels like his father's son when he is fighting from what he deems to be moral high ground. In the past, has taken on the stalkerazzi and tabloid television. His most recent donnybrook was with Bill O'Reilly, after O'Reilly reported on October 31, 2001, that the $125 million raised at a celebrity telethon for the United Way's September 11th Fund was being mishandled and misused. Although O'Reilly invited Clooney and others to appear on his show, Clooney declined, feeling O'Reilly was more interested in celebrity bashing than in hearing a substantive explanation of the fund's troubles. Says Clooney, "He challenged me to debate him, and I said, "I'd be thrilled to debate you on Larry King Live. That didn't happen. See, if he really cared about the issue, he'd have the debate on his competitor's show. It makes me mad when O'Reilly f**ks with something that's good and done for the right reasons."

Clooney's anger burns brightly toward those who would disguise info-tainment as news programming - probably because he reveres the golden age of television. He was a journalism major at Northern Kentucky University, and the way some artists long for Paris in the `20's (or London in the `60's), Clooney pines for the glory years of CBS in the 1950's and `60's.

The transition from prime-time luminary to aspiring Sidney Lumet may seem like a stretch for the former Facts of Life regular, but to his friends, directing was a logical step; as an actor, he'd always been interested in idiosyncratic storytelling. Steven Soderbergh remembers that when he first met with Clooney to discuss the possibility of Soderbergh's directing Out of Sight, he and Clooney bonded over a shared fondness for `70's movies. "Look at the choices George has made since that movie. He's been very director-driven," Soderbergh notes, alluding to the way Clooney has worked with David O. Russell (Three Kings), the Coen Brothers (O Brother, Where Art Thou? and Intolerable Cruelty) and himself.

Given his druthers, Clooney says he "would be happy just making movies for the Coen brothers and Steven (Soderbergh) for the rest of my career." He also thinks the economic of big-budget studio pictures don't make sense. These days he'd rather be involved with midsize projects than stuff on the scale of The Perfect Storm. "How a film costs $90 million is insane," he says. "And I know, because they'll pay me $20 million, which is dumb. If you're in the position I'm in, you should just work for a percentage and gamble. If the movie works, I make a shitload of money. If it doesn't, then I got the movie I wanted made."

Clooney admits he always figured he'd have at best a ten-year run as a movie star, so eventually he'd need something else to fall back on. If he didn't, he'd be lip-synching the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack in Branson, Missouri. He says he saw the fleeting nature of fame early one, when, at 21, he worked as the driver for his late aunt Rosemary when she toured as a singer in the New Four Girls Four with Martha Raye, Kay Starr, and Helen O'Connell. He recalls Raye making him stop the car so she could, as Clooney says, "just stick out her leg to take a leak on the side of the road," Clooney laughs, then adds, "Aunt Rosemary would say, `Don't turn around, George, or you'll learn too much about the aging process.'"

|

He first became involved with Confessions not as a director but as an actor and producer. The project was one of several recent movies, including the comedy Welcome to Collinwood, the thriller Insomnia, and the melodrama Far from Heaven, that Clooney wanted to get made through his and Soderbergh's production company. Written by Charlie Kaufman, the cult-inspiring screenwriter responsible for Being John Malkovich ad Adaptation, Confessions was seen as a hot script but a problematic green light. Since producer Andrew Lazar optioned the book and set it up at Warner Bros. In 1997, Mike Myers, Ben Stiller, Russell Crowe, and Johnny Depp all flirted with the lead. He first became involved with Confessions not as a director but as an actor and producer. The project was one of several recent movies, including the comedy Welcome to Collinwood, the thriller Insomnia, and the melodrama Far from Heaven, that Clooney wanted to get made through his and Soderbergh's production company. Written by Charlie Kaufman, the cult-inspiring screenwriter responsible for Being John Malkovich ad Adaptation, Confessions was seen as a hot script but a problematic green light. Since producer Andrew Lazar optioned the book and set it up at Warner Bros. In 1997, Mike Myers, Ben Stiller, Russell Crowe, and Johnny Depp all flirted with the lead.Aside from unstable creative elements, the major stumbling block to getting the movie made was a regime change at Warner. Although the outgoing studio head had been a fan of the project, Warner's new regime was pursuing franchises a la Scooby-Doo instead of scripts that included scenes such as a preteen Chuck Barris enjoying a blow job from his sister's 13-year-old friend. Warner Bros. gave Clooney, Soderbergh and Lazar a chance to set up Confessions at another studio. The dues ex machine arrived in the form of Miramax cochairman Harvey Weinstein and his executive vice president of production, Jon Gordon, who flew to the Ocean's Eleven set and met with Clooney. Clooney talked about how during his television remake of Fail Safe, he had quizzed director John Frankenheimer about a shot in an adaptation of The Snows of Kilimanjaro, in which the actor Robert Ryan steps seamlessly from one scene to another. Recalls Miramax's Gordon, "As we talked about Frankenheimer putting the camera right on Ryan's face and rotating the set behind him on a giant lazy-Susan, we were getting comfortable with him as a director."

The lazy-Susan set was one of the vintage TV tricks Clooney used to complete physical production two days ahead of schedule and bring the movie in on budget, at $30 million. He had other resources at his disposal, the first of which was the subject. Barris was relaxed about most of the artistic license that Kaufman had taken with his book, including such erroneous riffs as his being the illegitimate child of a serial killer. The one change Barris asked for - and received - was that he not be portrayed as a cokehead. As Barris told me, "Kaufman had me into drugs in the script, and I was never a druggie. My daughter died of a drug overdose, so I asked for that to be taken out."

|

As Clooney channel surfs, he settles on Team Impact, the strongmen-lay ministers who break bricks as they spout scripture. It seems Clooney could drink beer and bullshit all night. As Clooney channel surfs, he settles on Team Impact, the strongmen-lay ministers who break bricks as they spout scripture. It seems Clooney could drink beer and bullshit all night."So what did the folks from Universal think?" I ask, noticing that they hung around after the screening and talked to him about Leatherheads, a script chronicling the early days of the NFL.

"They liked Confessions a lot. I think I might end up directing a movie there. Maybe get Universal and Miramax to split it, because I owe Harvey," he replies.

And after talking about this professional evolution from actor to actor-director, we shift the conversation to whether he may also be ready to move on in his personal live. Clooney says he can imagine having grandchildren more easily than he can imagine himself married. "I have this old-world vision of family and grandkids, but I don't have a vision of me pushing strollers around, being a father," he admits. "I have some interesting children that I'm working on right now. They're called projects." Spoken like someone whose work will be his legacy, whose scripts and storyboards will keep him company when the whole wide world is half asleep.

|

|

|