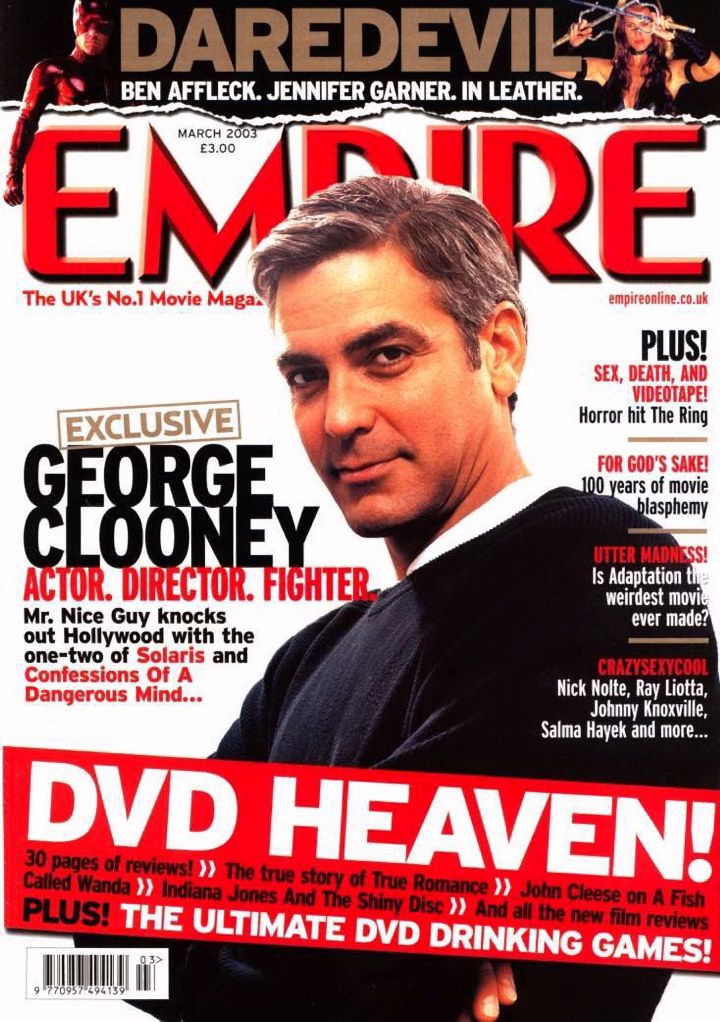

Daily Dose of George Clooney!

|

||

|

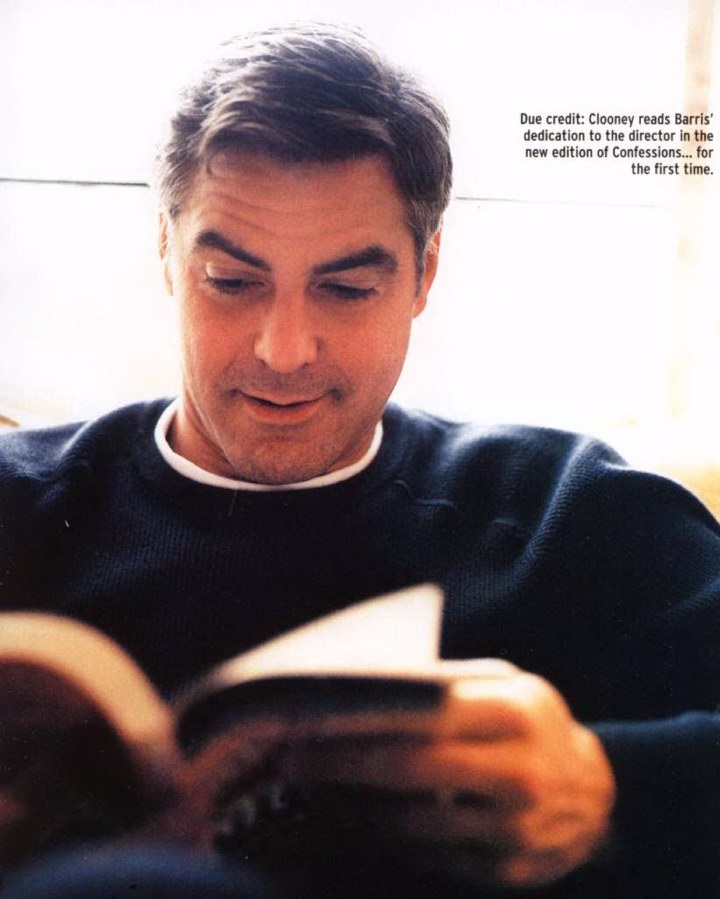

O, Lucky Man!

Colin Kennedy

Empire magazine

March 2003

George Clooney is gambling his reputation and his own money on two very risky projects, Solaris, and his directorial debut, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind. Not to worry - George always had lousy luck...

George Clooney has a letter he wants to show Empire. "I have it here somewhere," he says, scanning the penthouse suite of Claridge's, London. George Clooney likes to write letters - he cannot figure out email so he writes letters most every day. Steven Soderbergh, Clooney's good friend and production partner in Section Eight, has called George "the last great letter writer in America". Indeed, it was by way of letter that Clooney expressed his interest in tackling the enormously challenging part of widower Chris Kelvin in Soderbergh's remake of science-fiction drama Solaris. However, the letter Clooney wants to show Empire today is not written by George, it is addressed to him.

The author of this letter is Martin Bregman, an old-school producer who was recently responsible for the $100 million flop Pluto Nash, made out of Clooney's home studio, Warner Bros. Inside the dispatch, which Clooney describes as "the angriest letter I ever had in my life", is an invoice for $790.

|

|

Bregman's invoice dates back to spring 2002 and Montreal, where Clooney was shooting West Berlin exteriors for his directorial debut, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, at a place called Mel's Stages. Like nearly every other after noon on the 65-day shoot, four-and-a-half months of meticulous preproduction planning - during which Clooney and his creative team would get "blasted drunk" and draft some 980 storyboards -meant that the day's shooting had wrapped early. However, there was one last tracking shot Clooney had in mind, and all he needed was a camera crane. Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind - a dark comedy based on the memoirs of Gong Show host Chuck Barris - was a small film; such a small film, in fact, that the crew did not own a crane. But just behind a fence was an elephant's graveyard of film equipment, including a dormant crane. Mel told George that the equipment belonged to Pluto Nash and had been gathering dust for months. George figured that Warner Bros, for whom he has made hundreds of millions of dollars since his days on WB's hit TV show ER, probably owed him one, so Mel went off to fetch some bolt-cutters. They broke in, stole the crane, got the shot. The perfect crime. Only, of course, the notorious joker Clooney couldn't keep his big mouth shut and mentioned the lark on a talk show or two. Recently he mentioned Pluto Nash in the same breath as his own Warners flop, Batman & Robin. A week later, Bregman's invoice arrived.

"I thought he was kidding," Clooney says, picking up the story, until I read the very end which said, 'PS. I don't appreciate Pluto Nash being compared to Batman & Robin.' So I sent back two letters. On one I said, 'If You're kidding, open this letter,' and on the other, 'If you're serious, open this letter.' In the serious one I made the cheque payable to cash. In the other I made the cheque to 'Pluto Nash - to double your box office'."

|

|

George Clooney giggles at his latest jape. Clooney you might begin to appreciate from the very typical anecdote related above, is far too much of a grown-up to ever take this shit seriously. He shakes his pepper-coloured head, still baffled by Bregman's bray. "Some people just have too much time on their hands. "

Over the past decade since success visited Clooney relatively late in his Professional career, the actor has endeavoured to ensure that he never has too much time on his hands. Upon his return from Montreal he began postproduction duties on Confessions while simultaneously taking the toughest acting gig of his career in Solaris. He slept in his trailer and took a golf cart to an editing suite 100 yards from the Solaris set. He worked 18-hour days, the same hours he pulled when working weekends on ER while making a break for movie stardom in Batman & Robin. The same hours, he says, "I've had all along."

As if to prove the point, the bright, crisp December morning of our meeting is the Monday following the opening of Solaris in the US. "Oh, they're bad, yeah," Clooney says of the numbers. At the same time, Clooney spent the weekend showing Confessions to a BAFTA audience that included such seasoned directors as Terry Gilliarn and Stephen Frears, who called the shots on his live TV experiment, Fail Safe. Add to this a 2002 Section Eight production slate that yielded Ocean's 11, Insomnia, the quirky comedy Welcome To Collinwood and the Oscar-bound Far From Heaven, and you can see why Clooney as not yet found time for Christmas shopping.

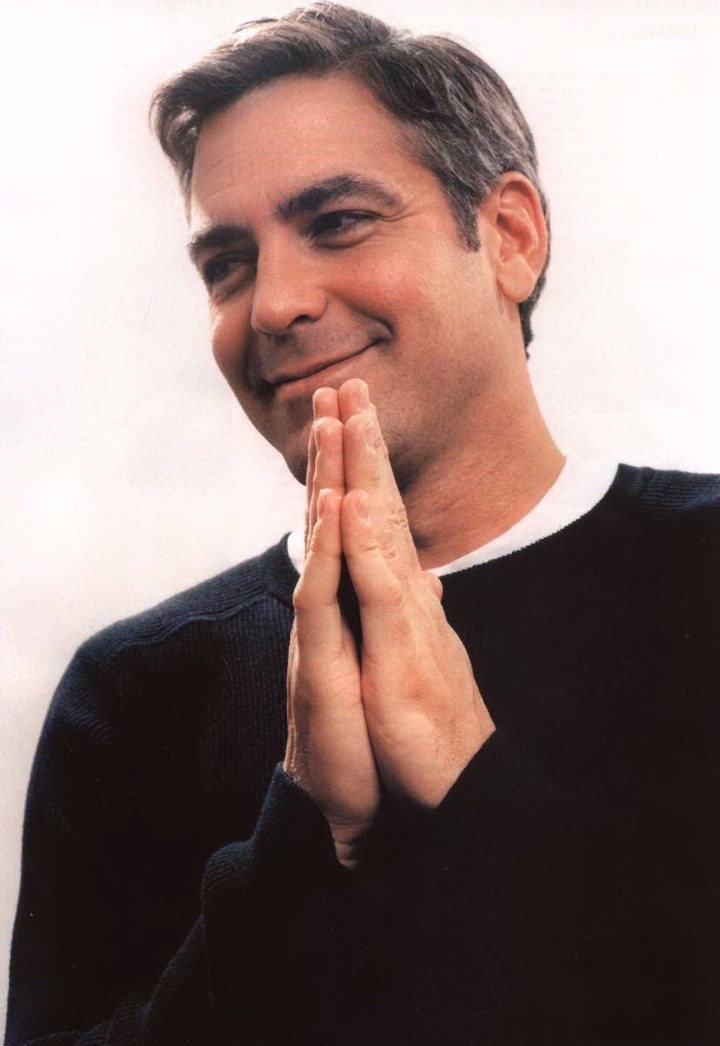

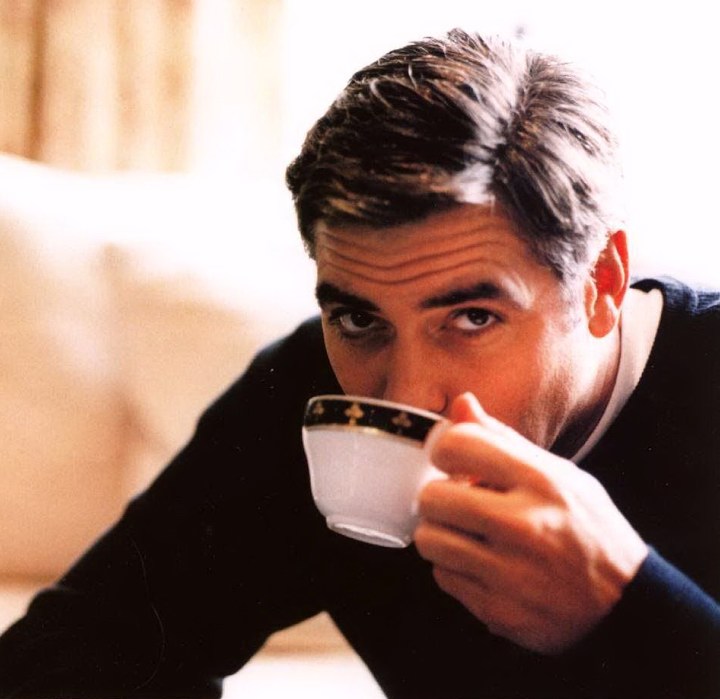

A couple of hours in his company, however, and you would never guess that Clooney had any other business to attend to. Despite the fact he is fighting a cold - not a hangover, he points out - he is at all times, as Julia Roberts dubbed him, a "charm monster". He signs Polaroids for the 'relatives' of Empire's extended photographic team. He pours English breakfast tea ("When in Rome...") for Empire and, upon discovering that he has only one proper cup, offers up his own mug. Understandably comfortable in his own skin (well, if you had that skin ... ), Clooney lies flat out on the sofa while chatting about the English weather, the Ryder Cup, jelly babies and the "bizarre Canadian sport" he caught on TV last night, curling.

Off the record, Clooney tells Empire some things about a Hollywood producer that should never be said in the presence of a journalist. On the record, he is hardly less forthcoming. As the Pluto Nash story illustrates, Clooney doesn't give a damn. He may spend his downtime shooting hoops and playing pranks but, when it comes to work, he is too old to play games. He has paid his dues and he always - always - puts his own money where his mouth is.

|

|

Clooney's current battle is with 20th Century Fox, the studio releasing Solaris worldwide. (Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind is a Miramax Picture, distributed in the UK by Buena Vista.) "To take things in order," as Clooney says, Fox have been "very brave" in taking on the $48 million Solaris. It is a difficult, adult piece of material. He also has a few friends at Fox - after all, he worked with them on One Fine Day. But studio suits are still suits. "Look," he says, "these are the same guys that saw One Fine Day and decided that we could beat Jerry Maguire and moved us from Valentine's Day to Christmas. Well, that was a dumb move."

With Soderbergh, Clooney and a producer - James Cameron - who made a couple of billion for the same studio a few years ago, Fox had high hopes for Solaris - Ocean's I I in Space, basically. "That's right," Clooney says, "Of course, if they'd read the script they would have known what they were getting. " (They could also have read Stanislaw Lem's source novel, or sat through Andrie Tarkovsky, 1972 four-hour version if they had needed any corroborative evidence.) Instead, what Fox got was a very formal, very quiet, extremely cerebral chamber piece. And what did Fox do next? "They did a dumb thing," Clooney says. "They panicked."

Clooney's reading on Solaris is simple: he thinks it's a masterpiece. (He's right, by the way.)

"Of course, that means that 50 per cent of the people can't stand it, which is okay. And then 50 per cent of the people go... 'Fuck."' Clooney is disappointed with the way this movie was marketed, not least the release of a misleading trailer- "The worst trailer since Universal put out the trailer for Out Of Sight"- but what really pisses him off is the thing with his ass.

There's a shot of George Clooneys ass in Solaris. You may have read about this. It caused controversy with the ratings board in America, the MPAA ruling that Clooney's ass was not suitable for children. Only it didn't really cause a fuss. The rating was never really going to be held up. The story, so Clooney maintains, was leaked by Fox. So desperate were they to stir up interest in Solaris that they made his bare butt the foundation stone of hteir marketing campaign.

"It immediately trivialises what Steven did," Clooney says, "and even more so what I was doing. And it makes me mad because you don't get the credit for doing what you're doing: which is sticking your neck out. I've had funny experiences in my career - Out Of Sight comes out and it bombs, Three Kings comes out and it doesn't do what they thought, O Brother comes out and doesn't do well. All the films that I really cared about under-performed but as time goes on, people still talk about those films. I said right at the beginning to the guys from Fox, 'Five years from now, you guys are all going to be sitting at a cocktail party, bragging about your involvement in this because that's the way it was with Out Of Sight at Universal, that's the way it was at Disney with 0 Brother.

"So you go, 'Well then, here's the deal, guys - it's not about an opening weekend. It's about a career and it's about building a set of films that you're proud of Period."

George Clooney is not exactly proud of Batman & Robin, but every so often he watches it anyway. He also watches some of his seven cancelled TV shows - the mullet years. "It's a good thing to do," Clooney argues- "When you have this horrible case of over-confidence, that's when you're almost always dead." Clooney suspects that Batman & Robin is perhaps the most important project he will ever do, in that it guaranteed he would never play safe again. "I think it's more of a risk for me to do Batman & Robin 2," he says, resisting the implication that working with directors like the Coen brothers and Steven Soderbergh could ever be considered brave. "I think it's a lot more of a risk to do commercial projects that end up not working. If you go and do Pluto Nash, that's a risk to me."

The last time George Clooney got paid was on a commercial project, Ocean's 11. He didn't ask for an upfront fee (he hasn't done that since The Perfect Storm) but both he and Brad Pitt saw more money on the back-end than they had ever made in their lives. "I think that's how it should be all the time," Clooney says. Indeed, the Section Eight business plan basically boils down to this: "Every odd year find an Ocean's I I -type film that can make a little money. "

The rest of the Section Eight philosophy is also striking in its simplicity. So simple, in fact, that you wonder why the rest of Hollywood can't function like this fledgling production company run by a TV actor and a movie nerd, both of whom have more flops to their name than hits.

Script development doesn't work, Section Eight says, so let's seek out great scripts on spec. (Soderbergh wrote his Solaris script on spec for Cameron's Lightstorm Entertainment.) Never take those executive producer fees unless you have something to offer and are really excited by the project. However, if a studio is willing to pay you $400,000 for something you want to work on, take the cash, roll it back into the picture. If you make money on the back-end, roll it into the next picture. (On the slightly disappointing Welcome To Collinwood, Clooney and Soderbergh were in for about $800,000, "with no design to get the money out".) Forget about opening weekends, think about your legacy. Keep in mind those films that you both love, especially American cinema from 1965 to '75: that's the benchmark. Participate in the filmmaking process by using whatever clout you have accumulated to protect the director. Take final cut so you can give it back to the director. Work with brilliant young directors.

|

|

Clooney did not intend to direct Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind. He did not intend to direct at all. However, he was such a fan of Charlie Kaufman's script - a deadpan adaptation of Barris' autobiography, in which the king of trash TV claimed a double life as a CIA hit man - that he had been attached to play Jim Byrd, Barris' CIA contact, for six years. Clooney had seen the script pass through many hands, including those of David Fincher and Curtis Hanson. He had seen preproduction start three times, putting almost $5 million of debt against the picture before a single shot had been canned. When Bryan Singer bailed in early 2001, six weeks before principal, Clooney had had enough. He decided to use his own company to get the damn thing made, even if he had to direct it himself. After all, he loved the script and harbours strong ideas about Barris' pernicious influence on American culture. And as the son of a Cincinnati talk show host, Clooney had grown up in Chuck's natural habitat ("I've been on those kind of sets my whole life").

Once Clooney had made the decision to direct, he took the gig seriously. First he returned to the original script - "It had been reduced into a screenplay that I didn't recognise" - cutting scenes which had seen the budget creep towards $40 million. He asked some famous friends - Drew Barrymore, Julia Roberts - to work for scale ($250,000) so he could get the budget under $30 million, including the bad debt, and persuaded Miramax boss, Harvey Weinstein, to risk everything on Clooney's preferred lead, Sam Rockwell. (Johnny Depp had been attached to play Barris, but Clooney, a Depp fan, did not want a famous actor playing another famous person.) As further insurance, Clooney had to offer Harv' another Miramax gig, somewhere down the line.

Negotiations completed, Clooney proved equally shrewd when it came to preparing for the first take. At home he has some 300 DVDs of movies he stole shots and transitions from, many of them from that '65 to '75 golden age. He read Sydney Lumet's book on directing and lifted ideas straight from the page. And, of course, there were those people he had worked with. "You pay attention," Clooney says with a smile.

"I'm always on the set. I love sets, I'm never in my trailer. " His key creatives were all filched from familiar sources: storyboard artist J. Todd Anderson from O Brother, Soderbergh's Oscarwinning editor Steve Mirrione, and Three Kings' cinematographer, Newton Thomas Sigel.

The resulting bouillabaisse is remarkable for many things, but mostly for being one of the most visually imaginative dramas of recent memory. If the hugely ambitious film has minor narrative issues, it is never uninteresting to look at. The digital process on the colour alone is ground-breaking. Despite admitting to being "intimidated" by cameras - "Lenses I get confused with. Stops I get confused with" Clooney talks for an hour about the technical details, enthusing about "brand-new" elements that one of Clooney's cohorts assured him will cause David Fincher "to shit himself ".

|

|

Soderbergh is perhaps a biased observer, but he's adamant that the technical accomplishment speaks for itself "What is most impressive about it is his understanding of film grammar. There are lots of people that have successful careers that still don't understand that. They know how to cover stuff, but they don't understand lenses and they don't understand eye-lines and cutting patterns, they just don't think that way. And he is really into that stuff. He absorbs stuff quickly."

So impressed is Soderbergh with Clooney's first effort that, if asked, he's happy to do a rewrite on Leatherheads, an American football comedy that might become George's next directing gig. If Leatherheads doesn't come off, Clooney will be left "looking for a job", but no doubt he'll find something new, something risky. With Max the pot-bellied pig his sole dependent, the eternally single Clooney will keep taking risks. But then, Clooney is a rich man, and rich men, he says, risk nothing.

The only time Clooney thinks he risked anything was in the early 80s when he quit a lucrative TV show because the producer, Ed Weinberger, was a bully. It's not that Weinberger treated young George badly - it's that Clooney refused to watch him "throw rocks" at other people. At the time, George was afraid that he was blowing his only shot. That, as the saying goes, he would never work in this town again. But George knew that this moment was about more than being the "afraid actor guy".

"Now it's about two guys in a room and one of them is out of line, and it's, 'Am I going to hit this guy?' No more is it about being an actor and a producer; now it's about, 'I've got to be a man."'

George Clooney walked away.

"And I realised then," says the man young George became, "that it comes down to not being afraid - if you're afraid, you're coming from that place, you're playing from fear. All bets are off when you're broke and you need a job, so that was the bravest thing I ever did.

A week later, Clooney was offered another job - by someone who hated Ed Weinberger. You make your own luck, so they say.

Perhaps it's just as well that Clooney isn't gambling with Solaris and Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind. The Ocean's 11 star is a lousy gambler. Matt Damon will not sit with him at a blackjack table and shoves him away if he comes near. Damon likes to tell the story of the time Clooney lost 20 hands of blackjack in a row, an almost impossible trick.

"Bad luck," Clooney shrugs. He pauses to ponder his career so far - all the great films he's made that didn't break box office records but eventually found the audience they deserved and muses again on the irony that, if even one of those movies had been a hit, he would have been "pigeon-holed" by Hollywood. "I've had a little bit of bad luck in things, y'know?"

We know. Long may it continue.

|

|

IN ONE RESPECT AT LEAST, George Clooney is exactly like you: he has never been to the Oscars. (Even more surprisingly, the actor owns only one ten year-old tux.) Of course, unlike the average Empire reader, Clooney gets asked to present an award every year and turns the Academy down flat. His thinking on this is simple: you should not go until you are nominated. If you think this distinguishes George from the usual pack of spotlight-hogging, soundbitespouting wannabes, you would be right.

However, the time may just have come for George Clooney to brush down that tuxedo. He has at least doubled his chances with arguably his best performance to date in Steven Soderbergh's Solaris, and a directorial debut of real merit in Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind. Even if both films fail to interest the Academy, it's a sure bet that Section Eight, the production company Clooney set up with Soderbergh in 2000, will have at least one representative at the big bash, with Far From Heaven's Julianne Moore a lock for Best Actress (admirably, Clooney won't go to the Oscars if Far From Heaven is nominated for Best Film as he wouldn't want to steal director Todd Haynes' glory).

To find out more about how George Clooney and Section Eight are beating Hollywood at its own game, check out the feature on page 66. And look out for those pesky nominations on February I I - this could yet be his year.

Colin Kennedy, Editor

A special thanks to Libby for he above article and pics!

|