| Italian: literally, comedy of the (performers') art:

theatrical form that flourished throughout Europe from the 16th through

the 18th century. Outside Italy, the form had its greatest success

in France, where it became the Comédie-Italienne. In

England, elements from it were naturalized in the harlequinade in

pantomime and in the Punch-and-Judy show, a puppet play involving

the commedia dell'arte character Punch.

The commedia dell'arte was a form

of popular theatre that emphasized ensemble acting; its improvisations

were set in a firm framework of masks and stock situations, and its plots

were frequently borrowed from the classical literary tradition of the commedia

erudita, or literary drama. Professional players who specialized

in one role developed an unmatched comic acting technique, which contributed

to the popularity of the itinerant commedia troupes that traveled throughout

Europe.

|

|

Many attempts have been made to find the

form's origins in preclassical and classical mime and

farce, and to trace a continuity from the classical Atellan play to the

commedia dell'arte's emergence in 16th-century Italy. Though

merely speculative, these conjectures have revealed the existence of

rustic regional dialect farces in Italy during the Middle Ages. Professional

companies then arose; these recruited unorganized strolling players, acrobats,

street entertainers, and a few better-educated adventurers, and they experimented

with forms suited to popular taste: vernacular dialects (the commedia erudita

was in Latin, or in an Italian not easily comprehensible to the general

public), plenty of comic action, and recognizable characters derived

from the exaggeration or parody of regional or stock fictional types.

It was the actors who gave the commedia dell'arte its impulse and

character, relying on their wits and capacity to create atmosphere and

convey character with little scenery or costume.

|

The decline of the commedia dell'arte

was due to a variety of factors.

Physical comedy came to dominate the performances because the rich verbal humour of the regional dialects was lost on foreign audiences. As the lazzi became routine, it lost its vitality - the actors stopped altering the characters, so that the roles became frozen and no longer reflected the conditions of real life, thus losing an important comic element. The later efforts of such playwrights as Carlo Goldoni (c.1707-93) to create a new, more realistic form of Italian comedy sealed the fate of the decaying threatrical form. The commedia dell'arte's last traces entered into pantomime as introduced in England (1702) by John Weaver at Drury Lane Theatre, and developed by John Rich at Lincoln's Inn Fields. It was taken from England to Copenhagen (1801), where, at the Tivoli Gardens, it still survives. Revivals of the form - however carefully copied their masks may be from contemporary illustrations, however witty their improvisation - can only approximate what the commedia dell'arte must have been. |

| A more important, if less obvious, legacy of the commedia dell'arte is its influence on other dramatic forms. Visiting commedia dell'arte troupes inspired national comedic drama in Germany, eastern Europe, and Spain. Other national dramatic forms absorbed the comic routines and plot devices of the commedia. Molière, who worked with Italian troupes in France, and Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare in England incorporated characters and devices from the commedia dell'arte in their written works. European puppet shows, the English harlequinade, French pantomime and the cinematic slapstick of Charlie Chaplin all recall the glorious comic form that once prevailed. |

|

In every sense, this was a

performer's theatre - the playwright and director were comparatively unknown.

The actors had to be inventive and competent in order to generate performances

that were consistently fresh and distinctive.

Thus, for an understanding of the commedia

dell'arte, the mask is often considered inclusive of the player.

These actors created the roles that define farce in modern performance art.

|

|

Early in the development of the commedia, the zanni had been differentiated into fools who were comic, rustic or witty. They were characterized by shrewdness and self-interest, much of their success dependent upon improvised action and topical jokes. The zanni used certain tricks of their trade: burle (practical jokes) -- though often the fool, thinking he had tricked the clown, had the tables turned on him by a rustic wit as clever, if not so nimble, as his own -- and lazzi (comic business). |

|

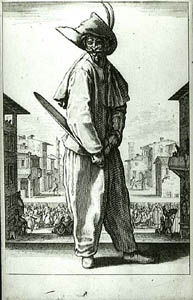

The lovers, played unmasked, were

scarcely true commedia dell'arte characters-- their popularity

depending on looks, grace, and fluency in an eloquent Tuscan dialect.

Pantalone (Pantaloon) was a Venetian merchant: serious, rarely consciously comic, and prone to long tirades and good advice. Dottore Gratiano was, in origin, a Bolognese lawyer; gullible and lecherous, he spoke in a pedantic mixture of Italian and Latin. The Capitano developed as a caricature of the Spanish braggart soldier, boasting of exploits abroad, running away from danger at home. He was turned into Scaramuccia by Tiberio Fiorillo, who, in Paris with his own troupe (1645-47), altered the captain's character to suit French taste. As Scaramouche, Fiorillo was notable for the subtlety and finesse of his miming. Pulcinella (related to the English Punchinello, or Punch) like Capitano,"outgrew" his mask and became a character in his own right, probably created by Silvio Fiorillo (d. c.1632) Arlecchino (Harlequin), one of the zanni, was created by Tristano Martinelli as the witty servant, nimble and gay: as a lover he became capricious, often heartless. Pedrolino was his counterpart. Doltish yet honest, he was often the victim of his fellow comedians' pranks. As Pierrot, his winsome character carried over into later French pantomimes. Columbina, a maidservant, was often paired in love matches with Arlecchino, Pedrolino, or the Capitano. With Harlequin she became a primary character in the English pantomime, the harlequinade. |

|

|

|