PART OF THE ARTSCHOOL

ONLINE NETWORK

PART OF THE ARTSCHOOL

ONLINE NETWORK

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF THE ARTIST CARAVAGGIO (1571-1610)

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF THE ARTIST CARAVAGGIO (1571-1610)

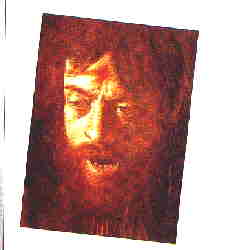

Caravaggio was one of the most extraordinary characters

in the history of art. He was not only the most powerful and influential

Italian painter of the 17th century, but also one of the prototypes of

the idea of the artist as a rebel outside the normal conventions of society.

His tempestuous career was punctuated by disputes with patrons about his

unconventional treatment of religious themes and by a series of acts of

physical violence.

After a struggle to establish himself in Rome, Caravaggio had achieved

widespread fame by his early 30s, his dramatic use of light and shade and

uncompromising realism creating a new pictorial vocabulary for European

art. At the height of his career, however, he fled Rome after killing a

man, and the rest of his short life was spent restlessly moving from place

to place. Caravaggio died aged 38.

Michelangelo Merisi, the son of Fermo di Bernardino Merisi,

was born in 1571, probably in Milan, not far from the village of Caravaggio

where his family came from (and which he named himself after some 20 years

later). His father who was majordomo (head butler) to Francesco

Sforza, Marchese di Caravaggio, died in 1577, and Michelangelo, with two

brothers (one of whom died in 1588) and a sister, was brought up by his

mother, Lucia Aratori.

In 1584, at the age of 12, Michelangelo joined the workshop of Milanese

painter Simone Peterzano as an apprentice. Nothing else is known about

his early life, except that his mother died in 1590, and two years later

Michelangelo, his brother and his sister divided the family property between

them. Michelangelo inherited 393 imperial pounds, which enabled him to

set off for Rome where successive popes had embarked on ambitious schemes

to embellish the town, and the prospect of large and lucrative commissions

attracted painters, sculptors and architects from all over Italy and beyond.

With large numbers of Italian and foreign painters flooding the Roman market,

the going was bound to be tough for a young, inexperienced artist trained

by a minor provincial master. Caravaggio should have been able to live

comfortably for several years on his inheritance but true to his later

lifestyle, he seems to have spent it quickly and unwisely and his early

years in Rome were marked by poverty.

There are no documents which record Caravaggio's activities in the Holy

City until 1599. It is generally agreed, however, that at some point he

was employed by Giuseppe Cesari, the Cavaliere d'Arpino, one of the leading

fresco painters of the day, who was working on huge papal and ecclesiastical

commissions. Yet even this promising association came to an abrupt end

when Caravaggio was committed to hospital, the Ospedale della Consolazione

- according to one source, because he had been kicked by a horse.

AN INFLUENTIAL PATRON

Some

time later, Caravaggio attracted the attention of Cardinal DelMonte, a

wealthy and sophisticated cleric, collector of paintings, lover of music,

and official cardinal-protector of the Accademia di San Luca, the

painters' academy in Rome. Del Monte represented the interests of Florence

at the papal court and resided in the Medici Palazzo Madama, near the Piazza

Navona.

Some

time later, Caravaggio attracted the attention of Cardinal DelMonte, a

wealthy and sophisticated cleric, collector of paintings, lover of music,

and official cardinal-protector of the Accademia di San Luca, the

painters' academy in Rome. Del Monte represented the interests of Florence

at the papal court and resided in the Medici Palazzo Madama, near the Piazza

Navona.

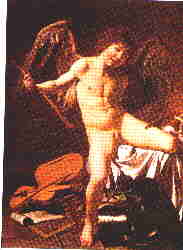

Caravaggio became a member of the Cardinal's household,

was given lodgings, food and a regular allowance, and he painted, in response,

a number of pictures of rather effeminate young men. That Del Monte was

a discreet hedonist, dallying with young boys, and that Caravaggio shared

his taste, has often been inferred from those early works; and even in

later, publicly displayed alterpieces, we find Caravaggio including angels

of an alluringly androgynous nature. On the other hand, some of the most

overtly erotic depictions of young boys, including the Victorious Cupid

(left), were painted for patrons who were beyond any suspicion of homoerotic

inclinations.

And it is surprising that at a time when homosexuality

was considered a serious crime, no suspicion seems to have fallen on Caravaggio

himself. Had there been any doubts about him, the many enemies he managed

to make in his short life would have exploited them publicly and with relish.

What gave rise to the rumours was the dubious reputation of his girlfriend

Lena, a prostitute, whom he was said to have used as the model for some

of his depictions of the Virgin Mary.

All of Caravaggio's early paintings were relatively small

works, still-lifes, genre-scenes and a few occasional religious subjects.

They were produced either for particular patrons, like Del Monte or the

Prior of the Ospedale della Consolazione, or for the open market,

to be sold by picture dealers. This was not the way to become rich and

famous. In the course of the Counter Reformation, Rome was witnessing an

unprecedented building-boom of new churches, and each new church required

chapel-decorations and alterpieces. This was where the big money was and

where public reputations were established. Caravaggio, now in his late

20s, must have been desperate to be given the chance to compete in this

lucretive market.

The chance came in 1599 with the commission of two large

paintings for the Contrarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi. The church

is only a few steps down the street from the Palazzo Madama, and Cardinal

Del Monte was probably instrumental in securing this important contract

for his protege.

AMBITIOUS PAINTINGS

Never

before, as far as we know, had Caravaggio attempted anything on a comparable

scale. And x-ray photographs of the Martyrdom of St Matthew have

revealed his initial uncertainty. He was fumbling about the right size

of his figures and for a convincing composition. After several attempts

to improve and correct his original version he was forced to start all

over again. Yet the final outcome seems to have been an overwhelming success;

even Caravaggio's arch-enemy, the painter Giovanni Baglione, who later

wrote a Life of Caravaggio, admitted that much: "This commission

made Caravaggio famous", he wrote, and added maliciously, "and the paintings

were escessively praised by evil people".

Never

before, as far as we know, had Caravaggio attempted anything on a comparable

scale. And x-ray photographs of the Martyrdom of St Matthew have

revealed his initial uncertainty. He was fumbling about the right size

of his figures and for a convincing composition. After several attempts

to improve and correct his original version he was forced to start all

over again. Yet the final outcome seems to have been an overwhelming success;

even Caravaggio's arch-enemy, the painter Giovanni Baglione, who later

wrote a Life of Caravaggio, admitted that much: "This commission

made Caravaggio famous", he wrote, and added maliciously, "and the paintings

were escessively praised by evil people".

This was Caravaggio's breakthrough. Large commissions

folowed one another in quick succession, and after a couple of years, the

painter's fame had spread right across Europe. The Dutch art-historian

Karel van Mander, living in Haarlem, wrote in 1603: "There is a certain

Michelangelo da Caravaggio, who is doing extraordinary things in Rome".

Yet is was not only the news of the painter's talent that had reached van

Mander; he had also been informed of Caravaggio's notorious life-style

and violent behaviour: "He does not study his art constantly, so that after

two weeks of work he will sally forth for two months with his rapier at

his side and his servant-boy after him, going from one tennis court to

another, always ready to argue or fight, so that he is impossible to get

along with". While van Mander's information about Caravaggio's paintings

was inaccurate, that about his public behaviour was correct.

From 1600 onward, since his first great public success,

Caravaggio appeared regularly in the protocols of the Roman police: in

November of that year he attacked a colleague with a stick, and the following

February he was brought before the magistrates, accused of having raised

his sword against a soilder. In 1603, Giovanni Baglione brought a libel

action againt Caravaggio and others; the painter was briefly imprisoned

and released only on condition that he stayed at home and promised not

to offend Baglione - any breach of these conditions would lead to him being

made a galley slave. In April 1604, he was accused of having thrown a dish

of hot artichokes in the face of a waiter in a restaurant, and of having

threatened him with his sword. Later in the same year he was arrested for

insulting a policeman. In 1605 he was arrested for carrying a sword and

a dagger without permission; brought before the magistrates for insulting

a lady and her daughter, and for attacking a notary in a quarrel over his

girlfriend; and finally he was accused by his landlady of not paying his

rent and of thowing stones through her windows.

Perhaps we should judge Caravaggio's character not simply

by his criminal records and his violent behaviour. He was supported and

protected by some of the most sophisticated patrons in Rome, including

Del Monte and the Marchese Giustiniani. Some of his best friends and companions

in his rakish adventures were well-educated and refined men. Giovanni Battista

Marino, perhaps the most erudite and cultivated poet of the age, had his

portrait painted by Caravaggio and immortalized his art in poems. And while

Caravaggio"s public statements about earlier and contemporary artists could

appear brutish and simplistic, he privately studied the art of Leonardo,

Raphael, Michelangelo, and the great Venetian painters with considerable

sensitivity and a fine understanding. We simply don't know enough about

his intimate life, his interests or learning to form a fuller and more

just image of his character than that provided by the criminal records

of the Roman police.

On 28 May 1606, Caravaggio's violent temper finally led

to disaster: unwilling to pay a wager of 10 scudi on a tennis match, he

and several friends got involved in a fierce fight with his opponent, a

certain Ranuccio Tommasoni, and his friends on the Campo Marzo. The painter

was badly wounded, and so was one of his supporters, a Captain Petronio,

who was subsequently imprisoned. Tommasoni, however, died from Caravaggio"s

attack.

FLIGHT FROM ROME

The painter went into hiding for three days, probably in

the palace of the Marchese Giustiniani, and then fled secretly from Rome,

which he was never to see again. Caravaggio's exact whereabouts over the

next five months are unclear. By October 1606 he was in Naples, well outside

papal jurisdiction. In less than a year he completed at least three major

altarpieces, waiting impatiently for his influential friends and patrons

in Rome to secure a papal pardon which would allow him to return. Yet the

authorities were slow to respond, and in July 1607 Caravaggio left Naples

and arrived on the island of Malta.

Whether he undertook the trip to Malta of his own accord,

presumably in the hope of being made a Knight of St John, or whether he

had been invited by the Maltese Knights to paint certain pictures, we do

not know. But Caravaggio's stay on the island was productive: in addition

to portraits, among them that of the Grandmaster Alof de Wignacourt, he

painted his largest work ever, the Beheading of St John, the patron

saint of the Knights Order.

On 14 July 1608, Caravaggio was made a Knight of the

Order of Obedience, obviously as a reward for his work. In addition, Bellori

reports, "the Grandmaster put a gold chain around his neck and made him

a gift of two Turkish slaves, along with other signs of esteem and appreciation

for his work." Caravaggio was not to enjoy the benefits of his new honor

for very long. According to Bellori, his "tormented nature" led him into

an ill-considered quarrel with a noble knight. Perhaps the news of his

Roman crime had caught up with him: in any case, Caravaggio was thrown

into prison. He managed to escape by night and fled to Sicily. The Knights

of Malta subsequently stripped the artist of all his honors and excluded

him from the Order.

After short stays in Syracuse, Messina and Palermo, and

the rapid completion of alterpieces in each of these towns, Caravaggio

returned to Naples. His fame enabled him to request and recieve large payments

for each work he undertook, but he was still a fugitive, by now perhaps

not only from papal justice but also that of the Maltese Knights. By October

1609 rumours had reached Rome that he had been killed or badly wounded

in Naples. According to Baglione, "his enemy finally caught up with him

and he was so severely slashed in the face that he was almost unrecognizable.

In Rome, Caravaggio's friends were still pressing for

a pardon, now supported by Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga, who had bought

his Death of the Virgin after it had been rejected by the priests

of Sta Maria della Scala. In the summer of 1610, Caravaggio left Naples

suddenly and set sail, on a samll boat, to Port'Ercole, a port about 80

miles north of Rome which was under Spanish protection. It is clear that

he expected to be able to return to Rome very soon but could not yet enter

papal territory. After four unhappy years of restlessness he could look

forward with confidence to rejoining his friends and patrons in the Holy

City. But this was not to happen.

Baglione, Caravaggio' s old enemy, has left us the most

vivid account of the artist's last days. Having gone ashore in Port'Ercole,

Caravaggio "was mistakenly captured and held for two days in prison and

when he was released, his boat was no longer to be found. This made him

furious, and in desperation he started out along the beach under the fierce

heat of the summer sun, trying to catch sight of the vessel that had his

belongings. Finally, he came to a place where he was put to bed with a

raging fever; and so, without the aid of God or man, in a few days he died,

as miserably as he had lived". Caravaggio died on 18 July 1610; he was

not even 40 years old.

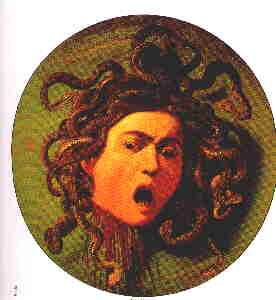

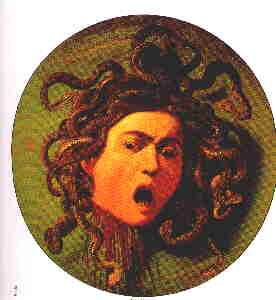

Medusa

GALLERY OF CARAVAGGIO PAINTINGS

Medusa

GALLERY OF CARAVAGGIO PAINTINGS

BACK TO MAIN PAGE

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF THE ARTIST CARAVAGGIO (1571-1610)

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF THE ARTIST CARAVAGGIO (1571-1610)

Some

time later, Caravaggio attracted the attention of Cardinal DelMonte, a

wealthy and sophisticated cleric, collector of paintings, lover of music,

and official cardinal-protector of the Accademia di San Luca, the

painters' academy in Rome. Del Monte represented the interests of Florence

at the papal court and resided in the Medici Palazzo Madama, near the Piazza

Navona.

Some

time later, Caravaggio attracted the attention of Cardinal DelMonte, a

wealthy and sophisticated cleric, collector of paintings, lover of music,

and official cardinal-protector of the Accademia di San Luca, the

painters' academy in Rome. Del Monte represented the interests of Florence

at the papal court and resided in the Medici Palazzo Madama, near the Piazza

Navona.

Never

before, as far as we know, had Caravaggio attempted anything on a comparable

scale. And x-ray photographs of the Martyrdom of St Matthew have

revealed his initial uncertainty. He was fumbling about the right size

of his figures and for a convincing composition. After several attempts

to improve and correct his original version he was forced to start all

over again. Yet the final outcome seems to have been an overwhelming success;

even Caravaggio's arch-enemy, the painter Giovanni Baglione, who later

wrote a Life of Caravaggio, admitted that much: "This commission

made Caravaggio famous", he wrote, and added maliciously, "and the paintings

were escessively praised by evil people".

Never

before, as far as we know, had Caravaggio attempted anything on a comparable

scale. And x-ray photographs of the Martyrdom of St Matthew have

revealed his initial uncertainty. He was fumbling about the right size

of his figures and for a convincing composition. After several attempts

to improve and correct his original version he was forced to start all

over again. Yet the final outcome seems to have been an overwhelming success;

even Caravaggio's arch-enemy, the painter Giovanni Baglione, who later

wrote a Life of Caravaggio, admitted that much: "This commission

made Caravaggio famous", he wrote, and added maliciously, "and the paintings

were escessively praised by evil people".