PART OF THE ARTSCHOOL

ONLINE NETWORK

PART OF THE ARTSCHOOL

ONLINE NETWORK

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF GEORGES SEURAT

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF GEORGES SEURAT

THE QUIET EXPERIMENTER

Georges-Pierre Seurat was born in Paris on 2 December 1859,

the son of comfortably-off parents. His father, a legal official, was a

solitary man with a taciturn and withdrawn manner which his son also inherited.

At every available opportunity, Antoine-Chrisostome took leave of his family

and disappeared to his villa in the suburbs to grow flowers and say mass

in the company of his gardener; he was only at home on Tuesdays. Suerat's

mother was quiet and unassuming, but it was she who gave some warmth and

continuity to his childhood.

The family apartment was on the Boulevard de Magenta,

close to the landscaped pleasure garden the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, where

young Georges and his mother spent much of their spare time. Such places,

and the people who frequented them, were to become the subject of some

of his greatest paintings.

THE HANDSOME STUDENT

As a young man Seurat was tall and handsome with "velvety

eyes" and a quiet, gentle voice. Reserved and dignified in dress as well

as manner, he was always neatly and correctly turned out: one friend described

him as looking like a floor-walker in a department store, while the sophisticated

and sharp-tongued Edgar Degas nicknamed him "the notary". He was serious

and intense - preferring to spend his money on books rather than on food

or drink - but his most pronounced characteristic was his secretiveness.

Despite many of the qualities of the perfect student,

Seurat did not particularly shine at school or at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts,

the official Paris art school, which he entered in 1878. But thanks to

a regular allowance, he never had any need to sell his work for a living

- nor to produce work that was salable. In 1879, a year of military service

broke into his artistic studies. Seurat was sent to the great military

port of Brest on the western coast of Brittany, where he fitted in easily

to barracks discipline and used his spare time to begin sketching figures

and ships.

Returning to Paris in 1880, the young artist initially

shared a cramped studio on the Left Bank with two student friends before

moving to a studio of his own, closer to his parent's home on the Right

Bank. For the next two years, he devoted himself to mastering the art of

black and white drawing.

The

year 1883 was spent on a huge canvas, Bathing at Asnieres (left),

his first major painting. In 1884, the Salon jury rejected it and Seurat

changed the direction of his career. From this year on, he scorned the

academic art of the Salon and allied himself with the young independent

painters.

The

year 1883 was spent on a huge canvas, Bathing at Asnieres (left),

his first major painting. In 1884, the Salon jury rejected it and Seurat

changed the direction of his career. From this year on, he scorned the

academic art of the Salon and allied himself with the young independent

painters.

An instinctively gifted painter, Seurat also had extraordinary

powers of concentration and perseverance, and took a dogged and single-minded

approach to his work. He was convinced of the rightness of his own opinions,

and of the importance of the "pointillist" method he was developing. Although

other painters turned to him as a leader, he seems to have inspired admiration

rather than affection. He in turn looked upon this admiration as naturally

befitting his superior intellect, hard work and achievement.

MEMBER OF THE COMMITTEE

In May and June 1884, Suerat's Bathing at Asnieres

hung at the first exhibition of the new group of Artistes Independents,

mounted in a temporary hut near the ruined Tuileries Palace. The show ended

in financial muddle, but out of the ensuing arguments a properly constituted

Societe des Artistes Independents emerged, committed to holding an annual

show with no jury. Seurat attended its committee meetings regularly, always

sitting in the same seat, quietly smoking his pipe.

At one such meeting, Seurat struck up a friendship with

Paul Signac. Signac was four years younger, a largely self-taught painter

who was influenced by the Impressionists and very receptive to Seurat's

theoretical ideas. The extrovert and enthusiastic Signac provided Seurat

with contact and moral support as he set about making his mark within the

avant-garde.

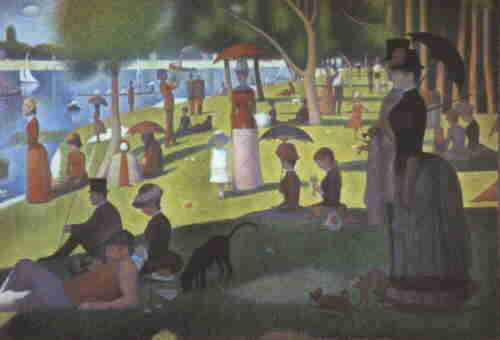

In the summer of 1884, Seurat embarked on another major

canvas, again depicting the popular boating place of Asnieres, but this

time focusing on the island of La Grande Jatte in the Seine. With characteristic

single-mindedness, he devoted his time entirely to the composition. Every

day for months he traveled to his chosen spot, where he would work all

morning. Each afternoon, he continued painting the giant canvas in his

studio.

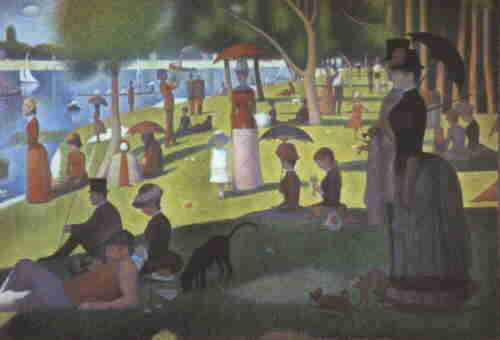

After

two years of concentrated, systematic work, Seurat completed the painting

in 1886, and exhibited it with the Impressionist group in May of that year.

La Grand Jatte (left) proved to be the main talking point of the

exhibition, and he was hailed by the critics as offering the most significant

way forward from Impressionism.

After

two years of concentrated, systematic work, Seurat completed the painting

in 1886, and exhibited it with the Impressionist group in May of that year.

La Grand Jatte (left) proved to be the main talking point of the

exhibition, and he was hailed by the critics as offering the most significant

way forward from Impressionism.

Felix Feneon, a sensitive and sympathetic young critic,

was particularly impressed. He christened Seurat and his associates the

Neo-Impressionists, and became an enthusiastic spokesman for them. In a

series of articles on contemporary art in the newly launched Vogue

magazine, Feneon paid special attention to Seurat's work, and expounded

his new method in scientific detail.

CENTER OF CONTROVERSY

Suddenly, Seurat found that he was the most controversial

figure on the artistic scene in Paris. He was now occupying a studio next

to Signac's on the Boulevard de Clichy in Montmartre. Here he was surrounded

by artists ranging from the conservative decorator Puvis de Chavannes,

whom he greatly admired, to more progressive contempories - including Degas,

Gauguin, Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec. He was at the center of artistic

debates, but he kept aloof from them.

Seurat's relative financial ease meant that he was unused

to dealing with potential clients, and his demands remained modest despite

his new fame. Once, when pressed to name his price for the painting he

was showing at "The Twenty" exhibition in Brussels, Seurat replied, "I

compute my expenses on the basis of one year at seven francs a day". His

attitude to his work was similarly down-to-earth and unromantic - he had

no pretensions to the status of genius. When some critics tried to describe

his work as poetic he contradicted them: "No, I apply my method and that

is all". He was, however, very concerned not to lose any credit for the

originality of his technique and guarded the details obsessively.

Seurat's life had begun to assume a regular pattern.

During the winter months, he would lock himself away in his studio working

on a big figure picture to exhibit in the spring, then he would spend the

summer months in one of the Normandy ports such as Honfleur, working on

smaller, less complex, marine paintings. Whether in Paris or at the coast,

Seurat was never a great socializer and in the last year of his life he

virtually cut himself off from friends. He could warm up in a one-on-one

situation, but by all accounts his conversation centered on his own artistic

concerns.

A SECRET FAMILY

Late in 1889, when Seurat was approaching 30, he moved away

from the bustling Boulevard de Clichy to a studio in a quieter street nearby,

where - unbeknown to his family and friends - he lived with a young model,

Madeleine Knobloch. In February 1890 she gave birth, in the studio, to

his son. Seurat legally acknowledged the child and gave him his own Christian

names in reverse. But it was not until two days before his death that he

introduced his young family to his mother.

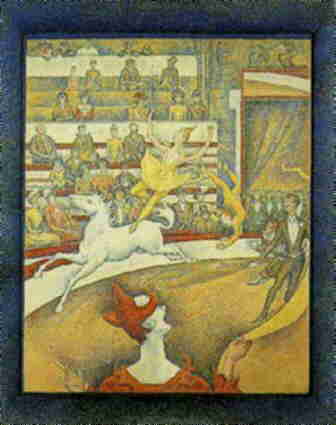

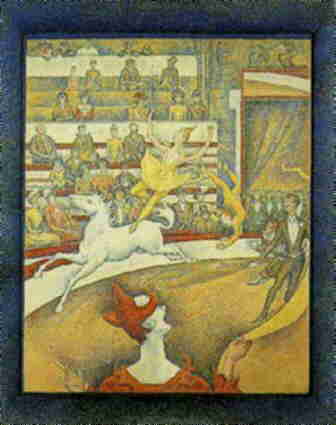

Georges Seurat died in March 1891, totally unexpectedly:

he seems to have contracted a form of meningitis. One week he was helping

to hang the paintings at the Independents exhibition and worrying about

the fact that his hero Puvis de Chavannes had walked past The Circus

(below) without so much as a glance; the following week he was dead at

just 31 years of age. Signac sadly concluded "our poor friend killed himself

by overwork".

SEURAT GALLERY

BACK TO START PAGE

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF GEORGES SEURAT

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF GEORGES SEURAT

The

year 1883 was spent on a huge canvas, Bathing at Asnieres (left),

his first major painting. In 1884, the Salon jury rejected it and Seurat

changed the direction of his career. From this year on, he scorned the

academic art of the Salon and allied himself with the young independent

painters.

The

year 1883 was spent on a huge canvas, Bathing at Asnieres (left),

his first major painting. In 1884, the Salon jury rejected it and Seurat

changed the direction of his career. From this year on, he scorned the

academic art of the Salon and allied himself with the young independent

painters.

After

two years of concentrated, systematic work, Seurat completed the painting

in 1886, and exhibited it with the Impressionist group in May of that year.

La Grand Jatte (left) proved to be the main talking point of the

exhibition, and he was hailed by the critics as offering the most significant

way forward from Impressionism.

After

two years of concentrated, systematic work, Seurat completed the painting

in 1886, and exhibited it with the Impressionist group in May of that year.

La Grand Jatte (left) proved to be the main talking point of the

exhibition, and he was hailed by the critics as offering the most significant

way forward from Impressionism.