PART OF THE ARTSCHOOL

ONLINE NETWORK

PART OF THE ARTSCHOOL

ONLINE NETWORK

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF MICHELANGELO

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF MICHELANGELO

Michelangelo di Ludovico Buonarroti Simoni (known as

Michelangelo) was born on 6 March 1475 in the Tuscan town of Caprese, near

Arezzo. His family were natives of Florence and they returned to the city

within a few weeks of the birth, when Ludovico Buonarroti's term as mayor

of Caprese had ended.

Soon after their arrival, the Buonarrotis sent the baby to a wet nurse

living on the family farm a few miles away in Settignano. This environment

seems to have had a crucial effect on Michelangelo, for the area around

Settignano was full of stone quarries. His wet nurse's father and husband

were both stonemasons, and Michelangelo often jested later in life that

"with my wet nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for

my statues".

From an early age the young Michelangelo was consumed with artistic ambition.

As a boy of 13, he persuaded his reluctant father to allow him to leave

his grammar school and become an apprentice to the artist Domenico Ghirlandaio,

one of the most successful fresco painters in Florence. The young Michelangelo's

prodigious skill - and, perhaps, his single-mindedness - soon aroused jealousy

among his fellow students in the garden. His biographer and friend, Giorgio

Vasari, tells of how another young sculpter, Pietro Torrigiano, later described

as a bully, punched him violently in the face, crushing and breaking his

nose. Michelangelo was deeply upset by the incident, and by the disfigurement

to his face - physically, and psychologically, it seems to have marked

him for life.

Michelangelo's skill now attracted the personal attention of Lorenzo de'

Medici (called the Magnificent), who was effective ruler of Florence at

the time. He was so impressed by a statue Michelangelo was carving that

he invited him to live in the Medici household.

CHANGING FORTUNES

Michelangelo spent two happy years in the Medici household

and worked on an impressive marble relief, The Battle of the Centaurs.

But when Lorenzo died in 1492, Michelangelo's fortunes began to take a

downward turn, and he went back to live with his father. Lorenzo's successor,

Piero de' Medici, was friendly to the artist but had little interest in

art. Indeed, the only work Piero commissioned from Michelangelo was a snowman,

a childish whim after a heavy snowfall in January 1494. As a consolation,

Michelangelo devoted his skills to a detailed study of anatomy by dissecting

corpses in the church of Santo Spirito - a curious privilege bestowed by

the prior in return for a carved wooden crucifix.

Under piero's rather haphazard reign, political Florence

became increasingly unstable and blood and thunder preachers found wide

audiences. A charismatic Dominican called Savonarola had a particularly

disturbing influence, denouncing the corruption of Florence and prophesying

the imminent doom of the sinful city. The invasion of Italy by Charles

VIII of France added fuel to the unrest. Apparently, with the words of

Savonarola ringing in his ears, Michelangelo packed up and left for Venice

in October 1494 - the first of his many "flights".

A VISIT TO ROME

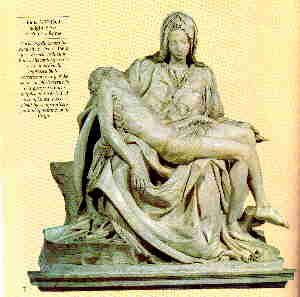

In 1496

Michelangelo was summoned to Rome as a result of the famous "Sleeping Cupid

affair" which had made him a reputation. Here he carved the marble Bacchus

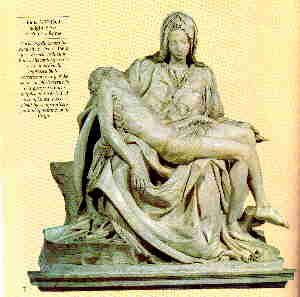

for the banker, Jacopo Galli, and the famous Pieta' (left), now

in St Peter's, for the French Cardinal Jean Bilheres de Lagraulas.

In 1496

Michelangelo was summoned to Rome as a result of the famous "Sleeping Cupid

affair" which had made him a reputation. Here he carved the marble Bacchus

for the banker, Jacopo Galli, and the famous Pieta' (left), now

in St Peter's, for the French Cardinal Jean Bilheres de Lagraulas.

The startling beauty and originality of the Pieta'

brought Michelangelo enduring fame. He was soon being heralded as Italy's

foremost sculptor. By 1501, he was able to return to Florence as a hero.

There he carved the magnificent statue of David further enhancing

his reputation. The statue was placed in front of the Palazzo della Signoria,

where it stood as a symbol of Republican freedom, courage and moral virtue.

The legendary sculptor went from strength to strength.

Soon after the death of Pope Alexander VI he was summoned back to Rome

to serve the new Pope, Julius II. Julius was the first of the seven popes

that Michelangelo worked for and their relationship was tempestuous.

In the spring of 1505, Julius commissioned Michelangelo

to create a tomb for him. It was to be a free-standing shrine with over

40 statues, a grand monument to himself. The scale of the project suited

the scope of Michelangelo's vision, and he spent eight months enthusiastically

quarrying marble at Carrara. But the Pope soon began to grow impatient

at the lack of results and gradually started to lose interest.

A PLAN FOR ST. PETER'S

By then, the Pope had conceived an even grander plan for

the complete rebuilding of the church of St. Peter's in Rome, and he had

entrusted the design to his favorite architect, Bramante. When Michelangelo

returned to Rome, burning with desire to make his magnificent vision live,

the Pope refused to see him.

Michelangelo left Rome for Florence in a fury, deliberately

leaving the day before the laying of the cornerstone for the new St. Peter's.

Pope Julius matched his wrath, however, and sent envoys and demands for

his return "by fair means or foul". Eventually Michelangelo succumbed,

and went to the Pope with a rope around his neck - a sarcastic gesture

of submission. Julius, who was in a more amenable mood, having just conquered

Bologna, rewarded Michelangelo with a commission for a colossal statue

of himself, to be cast in bronze. (The statue was later destroyed)

Michelangelo was still dreaming of completing the tomb,

but Julius was bent on redecorating the Sistine ceiling. Michelangelo eventually

accepted the commission, possibly goaded on by Bramante's suggestion that

he might lack the ability for such a task. But he always insisted that

painting was not his trade, and he again tried to get out of the commission

when spots of mold started to appear on the first section of his fresco.

By 1512, after four years of exhausting labor, however, the ceiling was

finally completed. When his work was unveiled, the effect was awe-inspiring

and people would travel hundreds of miles to see this work of an "angel".

As usual, Michelangelo sent the money he received for the work to his demanding

family.

Julius died in 1513, leaving money for the completion

of his tomb, and Michelangelo moved some marble he had quarried from his

workshop near St. Peter's to a house in the Macel de' Corvi, which he kept

from 1513 until his death. Successive popes were keen that Michelangelo

should work for their own glory, and distracted him with other commissions.

Then, in 1527, Rome was sacked by the Imperial troops

of Charles V, a mainly protestant army bent on the destruction of the Papacy.

An orgy of murder and pillage followed and Pope Clement VII was imprisoned

in the Castel Sant' Angelo. The Medici were yet again expelled from Florence,

and the republicans put the artist in charge of the fortifications of his

native city. In September 1529, fearing treachery, Michelangelo fled wisely

to Venice.

Eventually Pope Clement VII, then restored to power in

Rome, wrote to pardon Michelangelo and ordered him to continue work on

a chapel for the Medicis at San Lorenzo in Florence. Michelangelo finished

the tombs for the Medici chapel, but in 1534, three years after his father's

death, he left Florence in the tyrannical grip of Alessandro de' Medici,

never to return.

Michelangelo went to Rome, where Pope Clement had in

mind a grandiose scheme for the decoration of the altar wall of the Sistine

Chapel. Clement died before the painting was begun, but his successor,

Paul III, set him to work on the project. The Last Judgment was

painted from 1536 to 1541, and is a terrifying vision expressing the artist's

own mental suffering.

NEW FRIENDS

Michelangelo had always been a practicing Catholic and was

a deeply pious man. In later life, his religion became profoundly important

to him. This was partly the result of his great affection and admiration

for Vittoria Colonna, the Marchioness of Pescara - the only woman with

whom he had a special relationship.

For Michelangelo was widely believed to be homosexual

and it is true that he showed a preoccupation with the male nude unmatched

by any other artist. In the 1530's, he seems to have fallen in love with

a beautiful young nobelman, Tommaso Cavalieri, to whom he wrote many love

sonnets. Michelangelo insisted that their friendship was Platonic - he

believed that a beautiful body was the outward manifestation of a beautiful

soul.

Michelangelo was naturally a recluse. He was melancholic

and introverted, but at the same time emotional and explosive. He lived

a temperate life, but in a fair degree of domestic squalor which no servant

would tolerate for long. He preferred to be alone "like a genie shut up

inside a bottle", contemplating death. In 1544 and 1545 he suffered two

illnesses which did actually bring him close to death. Evidently the great

papal commissions had weakened his condition.

Paul III made Michelangelo Architect-in-Chief of St.

Peter's, and his work on the church continued throughout the rest of his

life, under three successive popes - Julius II, Paul IV, and Pius IV. He

tried to return to the simplicity of his old rival Bramante's design, but

St. Peter.s was not finished in his lifetime, nor exactly to his designs.

Finally, in his old age, Michelangelo also had time to

work for himself and the sculptures of this period, such as the Duomo

Pieta' (left), reveal an intense spirituality and tenderness.

Pope Julius II used to remark that he would gladly surrender

some of his own years and blood to prolong Michelangelo's life, so that

the world would not be deprived too soon of the sculptor's genius. He also

had a desire to have Michelangelo embalmed so that his remains, like his

works, would be eternal. As it happened, Michelangelo outlived Julius II,

and was buried with great pomp and circumstance after his death on 18 February

1564.

THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE

THE SISTINE CHAPEL

On 10 May 1508 Michelangelo signed the contract for the decoration

of the Sistine Ceiling - a momentous task which was to pose one of the

greatest human as well as artistic challenges. The work had been commissioned

by Pope Julius II, whose uncle Sixtus IV, had authorized the building of

the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. On the walls were 15th-century frescoes

showing scenes from the life of Moses and Christ, while the ceiling was

a traditional star-spangled blue. Julius, however, who was bent on the

whole scale "restoration" of Christian Rome, wanted something grander and

more "progressive".

By July, the scaffolding was in place and the cardinals,

who had complained of the noise and rubble, were able to conduct their

services in peace. A few weeks later, five young assistants arrived in

Rome, but on finding the door of the Chapel bolted, they took the hint

and returned to Florence. In the end, Michelangelo painted the ceiling

almost entirely alone, triumphing over months of tremendous physical discomfort.

The completed ceiling was unveiled on 31 October 1512.

"When the work was thrown open", reported Giorgio Vasari, "the whole world

came running to see what Michelangelo had done; and certainly it was such

as to make everyone speechless with astonishment".

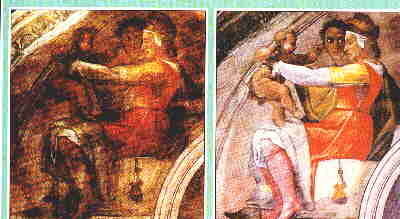

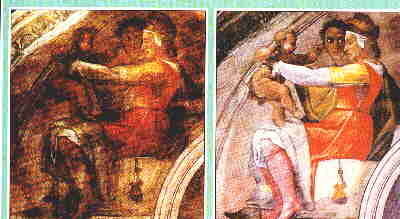

(left) The ""ignudi", or nudes, seated directly

above the Prophets (on the ceiling) and Sibyls, may represent "angels",

although they seem to be an entirely personal contribution. They support

bronze medallions, attached to garlands or acorns - the heraldic device

of the Della Rovere family of Julius II.

(right) In the 1980's restoration work began on the Sistine

Ceiling frescoes. Centuries of grime was removed to reveal the original

state of Michelangelo's paintings. This lunette with Matthan, one of the

Ancestors of Christ, shows that the artist's colors are much crisper and

brighter than is often supposed.

GALLERY OF MICHAELANGELO PAINTINGS

BACK TO HOME PAGE

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF MICHELANGELO

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF MICHELANGELO

In 1496

Michelangelo was summoned to Rome as a result of the famous "Sleeping Cupid

affair" which had made him a reputation. Here he carved the marble Bacchus

for the banker, Jacopo Galli, and the famous Pieta' (left), now

in St Peter's, for the French Cardinal Jean Bilheres de Lagraulas.

In 1496

Michelangelo was summoned to Rome as a result of the famous "Sleeping Cupid

affair" which had made him a reputation. Here he carved the marble Bacchus

for the banker, Jacopo Galli, and the famous Pieta' (left), now

in St Peter's, for the French Cardinal Jean Bilheres de Lagraulas.