The life and times of Vincent van

Gogh

The life and times of Vincent van

Gogh

Modern expressionism stems directly from the tragic Dutchman, Vincent van

Gogh (1853 - 1890), a man a little older than Georges Seurat, who died

a year before Seurat did. Both stemming from impressionism, these contemporaries

could hardly be more unlike - Seurat with his calculation, his method,

his deliberation, van Gogh with his passion, his shattering vehemence.

Modern expressionism stems directly from the tragic Dutchman, Vincent van

Gogh (1853 - 1890), a man a little older than Georges Seurat, who died

a year before Seurat did. Both stemming from impressionism, these contemporaries

could hardly be more unlike - Seurat with his calculation, his method,

his deliberation, van Gogh with his passion, his shattering vehemence. Instead of La Grande Jatte (see Seurat), so cool, so defined, so

self contained, van Gogh gives us The Starry Night, where a whirling

force catapults across the sky and writhes upward from the earth, where

planets burst with their own energy and all the universe surges and pulsates

in a release of intolerable vitality.

Instead of La Grande Jatte (see Seurat), so cool, so defined, so

self contained, van Gogh gives us The Starry Night, where a whirling

force catapults across the sky and writhes upward from the earth, where

planets burst with their own energy and all the universe surges and pulsates

in a release of intolerable vitality.

Like

all the most affecting expressionist creations, The Starry Night

seems to have welled forth onto the canvas spontaneously, as if the creative

act were a compulsive physical one beyond the artist's power to restrain.

"Inspiration" as a kind of frenzied enchantment visited upon a painter,

a paroxysm calling forth images only halfwelled, is a justifiable conception

in van Gogh's case, if it is ever justifiable at all.

THE EARLY DAYS

Indeed van

Gogh must have been a much easier man to read about than he was to be around.

Small, ugly and intense, without charm or wit, intelligent but narrow,

socially ackward, ill dressed as a point of honor, tortured by religious

confusions, yearning for affection but egotistical and stubborn, eager

to please but resentful of criticism, he was one of those people who hold

noble ideas too nobly, who offer their love as an embarrassing gift, whom

one would like to like but whose presence is a burden. He seemed incapable

of enjoying himself or of giving pleasure; in all the letters he wrote

-- and he wrote beautifully in them -- there is no indication that he ever

took anything casually for a moment.

The

men of van Gogh's family were traditionally clergymen, but two uncles had

a prosperous gallery in The Hague, which they sold to the international

art dealer Goupil. Through this connection young Vincent, at sixteen, obtained

a place with Goupil, first in The Hague, then in London, and finally in

the main branch of the firm in Paris. But he failed. Never suave, always

opinionated, no friend of the rich, who buy pictures, he ended by irritating

so many customers that he was dismissed. Turning to religion, he failed

at the theological seminary. When he sought to sacrifice himself in service

as a combination evangelist and social worker among miners in a desperately

depressed and gloomy area, he failed. He subjected himself to all

the hardships of his poverty-stricken parishioners -- their miserable quarters,

their abominable diet. He slept on a hard board and a straw mattress when

he could have had a comfortable bed. The miners laughed at him, their children

hooted at him in the streets. Twice in love, he was twice rejected -- once

by his landlady's daughter in London, once by a cousin. Rejected by the

women he wanted to love, rejected by the people he wanted to help, van

Gogh attempted to fulfill himself on both scores by living with and caring

for a prostitute he picked up on the street, ugly, stupid, and pregnant.

This idyll, which could have been inspired by Dostoevski, endured for twenty

months.

It was

not until 1880, when he was twenty-seven years old, that van Gogh decided

to be a painter. He entered this new life not as one enters a profession

but as one accepts a spiritual calling, in foreknowledge of self-sacrifice.

His

will, his compulsion, to paint as a direct expression of self, as a psychological

need quite aside from professional ambition or the will to fame, no matter

what suffering would be involved, sets van Gogh apart from the impressionists,

who had fought stubbornly in the face of every discouragement but had always

been professional painters, careerists. Delacroix had established the idea

of the painter's right to paint as he pleased, to enter into a pitched

battle against entrenched manners of painting; Courbet had continued to

fight, more as an individual than as a member of an organized school with

a leader and henchmen; the impressionists had further abandoned the pre-nineteenth-century

idea of a painter as a craftsman with a product to sell in satisfaction

of a demand, and finally were to succeed in creating a demand by bringing

public taste into line with their standards. But they were professionals.

With van Gogh the balance swings to the other side. Although he yearned

for attention, although he exhibited when he could, and finally managed

to sell one painting, he was not first of all a man making his way in a

profession. He was a man intent on saving his soul, in creating his very

being, by painting pictures.

Van

Gogh had begun to draw at the time of his failure as an evangelist among

the miners, and had attended classes for a while at the academy in Brussels.

He began his serious study as an overage beginner in the academic art school

at The Hague, but did not stay long. He had a cousin there, Anton Mauve,

one of the most popular painters of the day. Mauve was a painter of sentimentalized

humanitarian subjects in the degenerating tradition of the Barbizon school.

The association did not last long, ending as so many of van Gogh's associations

did, in a quarrel. This was also his time of association with the prostitute

Sien, which had become intolerable. Van Gogh left to paint on his own in

the town of Neunen, where his father was now pastor. He puzzled and frightened

the townsfolk; the pastor forbade them to pose for his son.

The

work from this period -- from his first efforts in 1880 until the beginning

of 1886 -- is a continuation of the obsessive humanitarianism that had

lead Vincent into evangelical work, and it has the same excess of gloomy

fervor that had lead to his failure in it. His subjects are poor people,

squalid streets or farms, miners and peasants broken by poverty and toil,

the inmates of almhouses. He draws in crayon or charcoal, and in his paintings

his colors are as depressing as his subjects. His first large, ambitious

composition, of which there are three versions, was The Potato Eaters,

painted in the dismal browns and greenish blacks of the period.

"I

have tried to make it clear how these people, eating their potatoes under

the lamplight, have dug the earth with these very hands they put in the

dish....I am not at all anxious for everyone to like or admire it at once."

"I

have tried to make it clear how these people, eating their potatoes under

the lamplight, have dug the earth with these very hands they put in the

dish....I am not at all anxious for everyone to like or admire it at once."

His taste

in painting generally was also involved more with humanitarian ideas than

with aesthetic values. He admired Millet, and another French painter of

peasants, l'Hermitte, and the Hollander Josef Israels, although he objected

when these men idealized their subjects, as they usually did. He also named

Daumier and Rembrandt, again largely for their subject matter. He read

such English authors as George Eliot and Dickens, who wrote of the poor

and oppressed. The American writer Harriet Beecher Stowe was another favorite;

Uncle Tom's Cabin, with its pathetic slaves, stirred him deeply.

He read the sociological realistic novels of Zola. But he also read the

aesthetic de Goncourts. He hardly knew the impressionistic painters at

this time.

Early

in 1886 van Gogh suddenly left Holland for Paris. It seems to have been

an abrupt decision. It was certainly an important one. He had gone to Antwerp

and had studied for a while at the academy there, but found it dull and

restricting. Academic training was intolerable to him because it seemed

divorced from the earthly and simple values he was interested in. But he

was a clumsy draughtsman and he knew it, and he felt the need of stimulation

and excitement from other painters. If he could not tolerate the school

in Antwerp, neither could he go back to working on his own in the backward

rural community. His brother Theo was directing a small gallery in Paris,

a branch of Goupil's. Vincent wrote him that he would be in the Louvre

at a certain hour, and asked Theo to meet him there.

Later,

Theo was to recognize his brother's power as an artist, but at this time

Vincent was only the family problem, a maladjusted and difficult man whose

drawing was nothing more than an emotional stopgap, who was reaching his

middle thirties and could not hold a job, who had shown that he was impractical

and unstable and would have to be either supported or abandoned to the

most desperate circumstances of life, to vagabondage, starvation, the almshouse.

The story of Vincent and Theo from now on is a poignant one. Their letters,

up to Vincent's last unfinished one written just before his suicide, read

like a fine novel and have furnished the material for several poor ones.

In his letters Vincent reveals the gentleness and above all the clarity

of thought that were so rare when he spoke and not at all apparent in his

actions. His torment is equally revealed, and Theo's patience and love.

But in their day-to-day relationships when they were together, Vincent

remained a problem -- stubborn, hypersensitive, and eccentric. Theo's heart

must have sunk when he read Vincent's letter telling of his decision to

come to Paris, but he took his brother into his flat, supported him from

his own limited income, and set about helping him to find his way toward

a solution of his problems.

Theo's

gallery handled work by all of the major impressionists as well as the

standard Salon masters who sold much better. Theo himself, like any good

dealer, was always hunting new talent and had scouted the impressionists

group shows with more sympathy than most dealers risked. Vincent's arrival

coincided with the first impressionists exhibition, when only a few of

the original group were exhibiting and a special room had been given over

to the neo-impressionists, including Seurat with La Grande Jatte.

The impressionists' happy, brightly tinted art did not immediately

affect Vincent. He entered the studio of Cormon, a conventional painter

who gave his students sound training in the imitation of the model. Here,

a grown man among youngsters, Vincent labored industriously, correcting

his drawings until he had erased holes in the paper, irritating everyone,

the class freak. Just how he managed to get accepted in a class limited

to thirty students, with a waiting list, is a question. Theo's position

as a dealer probably helped. Lautrec was among the students and Vincent

came to his studio from time to time, but he was an odd ball in the effervescent

company and after standing hopefully on the sidelines for a while he would

disappear. Lautrec did a sketch of him at a cafe table; it shows a thin,

bearded man leaning forward intently.

The

stimulation and the new ideas Vincent had come to Paris to find, came not

from the young men at Cormon's studio but from the patriarch of the impressionists,

Pissarro, reappearing yet again in his constant role of saint. As he had

done with Cezanne, Pissarro now induced Vincent to abandon his gloomy palette

and turgid shadows for the bright, high-keyed colorism of the impressionists.

But the transformation was more than a technical one; the spirit of Vincent's

art was equally changed. One of his earliest existing drawings, done at

about the time of his decision to work seriously at art, shows, as he described

it in a letter to Theo, ".........miners, men and women, going to the shaft

in the morning through the snow, by a path along a hedge of thorns; shadows

that pass, dimly visible in the twilight. In the background the large constructions

of the mine, and the heaps of clinkers, stand out vaguely against the sky......do

you think the idea good?" Good or bad, the idea was typical of his preoccupation

at that time with the hard lot of common people, full of cold, gloom, and

miserable hardship.

But

now when he paints the Factories at Clichy he has stopped seeing

and thinking in terms of oppressed workers, blackened

chimneys, belching smoke, piles of cinders and slag, and sees instead a

blue sky, red roofs, a foreground of slashing yellows and greens,

all singing in the open air.

But

now when he paints the Factories at Clichy he has stopped seeing

and thinking in terms of oppressed workers, blackened

chimneys, belching smoke, piles of cinders and slag, and sees instead a

blue sky, red roofs, a foreground of slashing yellows and greens,

all singing in the open air.

From

the broken strokes of impressionism and the uniform dots of pointillism

(Vincent had made a brief sally in this latter direction) he developed

a way of painting in short, choppy strokes of bright color, like elongation's

of the pointillist dots, which later were to bend and writhe and to be

reflected also in drawings of the greatest expressive economy. Suddenly

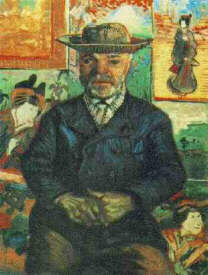

he is an artist, suddenly he is his own man. The

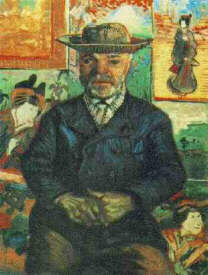

contrast between Old Shoes and the portrait of Pere Tanguy painted

the same year is complete. The old shoes are vigorously painted,

but the color and the implied humanitarianism are still on the dull and

rather heavyhanded that is so bothersome in The Potato Eaters.

But

Pere Tanguy suddenly lives, as no other of Vincent's images had

lived until then, and Vincent himself suddenly lives as a fulfilled painter.

But

Pere Tanguy suddenly lives, as no other of Vincent's images had

lived until then, and Vincent himself suddenly lives as a fulfilled painter.

Julien

Tanguy, affectionately called Pere Tanguy, was a color grinder who as a

traveling paint salesman had met most of the impressionist during

their most difficult days before 1870. When

he opened his own small shop of artists' materials in Montmartre he began

"buying" their paintings, which usually meant accepting them in exchange

for supplies. He also kept their work on hand for chance sales, and thus

grew into a collector and art dealer. He was particularly fond of Cezanne;

during the years of Cezanne's obscurity as a voluntary exile in Aix, his

paintings could be seen only at Pere Tanguy's. There were times when Monet

and Sisley would have been without materi als to paint with if it had not

been for this fatherly man. Madame Tanguy did not share his confidence

or his interest in those painters who, like van Gogh, used a great deal

of paint but were totally unsaleable.

In February,

1888, Vincent van Gogh left paris for Arles, in the south of France, where

his impressionism exploration was to begin in earnest.

ARLES, SAINT-REMY, AND AUVERS

The events of van Gogh's life between his departure from Paris in early

1888 until his suicide in July, 1890, are well enough known to have established

him in the popular mind as the archetype of the Mad Genius. Not mad, he

was an unstable personality who in the last two years of his life was subject

to epileptic seizures. Not quite a genius, he was a painter who in his

last two years produced a life work of extremist originality, combining

theory with a high degree of personal emotionalism. Because the events

of his life are dramatic enough to be disproportionately intrusive in a

discussion of his painting, they must be summarized first:

Vincent

left Paris in a fit of despondency to which many factors contributed. He

was irritated with the squabbling and bickering that, he found, was the

form usually taken by the stimulating discussions he had hoped for among

painters. Not only was he dependent on his brother Theo, but he felt that

he was in his way -- and he was. And in any case, Paris in February is

not a cheerful city in the low-income bracket. For a painter who had suddenly

discovered color it was gray, its studios dreary. By temperament Vincent

was restless. He had lived his life feeling that what he was hunting was

just around the corner. This time he thought it lay in the brilliant sun

and the simpler life of a small Provencal city. And this time it did.

Theo

gave him an allowance and he set himself up in Arles. For this man of thirty-five

it was like a youth's first discovery of the world on his own. Before long

he was working so hard that he had several fainting spells. Or perhaps

these were the first indication of the malady that was about to make itself

apparent. It was also just the time of the arrival in Arles of the painter

Gauguin.

Gauguin

was a fantastic and to van Gogh a glamorous personality, with barbarous

and brutal good looks the ugly little man must have envied, and an established

reputation among avant-garde painters. The men had met in Paris but did

not know one another very well in spite of Vincent's strong attraction

toward Gauguin. Gauguin was somewhat older, and there is a hint of adolescent

hero worship in van Gogh's feeling for him. He urged Gauguin to visit him

in Arles; Gauguin finally consented. As far as their painting was concerned

there was an important mutual influence. As far as their life together

was concerned there were tensions beyond endurance, at least beyond Vincent's,

and in an incident that apparently will never be clarified in its

details there was a violent quarrel, after which Vincent went to his room,

cut off an ear, wrapped it up, and delivered it to one of the girls in

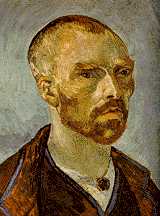

a brothel that he had frequented with Gauguin. This was during the last

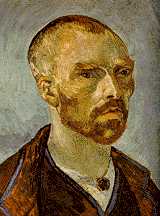

weeks of 1888. Shortly before, he had painted a self portrait as a present

for Gauguin (top of page); the words "a' mon ami Paul" are still

faintly discernible along the upper left border. The Arles experience had

begun with the happiest period of van Gogh's life; but the face in the

self-portrait for Gauguin is already the face of a man pushed to the limits

of endurance, and the remainder of Vincent's life was torment beyond anything

he had endured before.

During

the first five months of 1889 he remained in Arles, with intermittent periods

in the hospital as his seizures recurred. He suffered hallucinations, and

his irrational behavior got him into trouble with the townspeople, as had

happened elsewhere. Then for a year -- May 1889 to May 1890 -- he was an

inmate of the asylum at Saint-Remy, near by, where he had comparative freedom

and could receive immediate treatment - of a kind - during seizures. He

worked passionately. The Starry Night was painted at Saint-Remy.

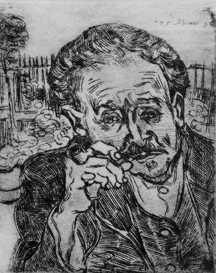

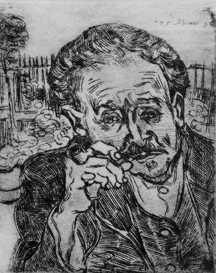

By May

the seizures seem to have relented and he was thought well enough to return

to the north. He went to Auvers, not far from Paris, where Pissarro lived

and had worked with Cezanne. Pissarro would have taken Vincent into his

own house but his wife, understandably objected. The immediate reason for

the choice of Auvers was the presence there of Dr. Paul Gachet, a physician

who had special

qualifications

for this special case since he was a friend of Pissarro's and Cezanne's

and some of the other impressionists - whom he had frequently treated without

a fee - and was as interested in art as he was medicine.

qualifications

for this special case since he was a friend of Pissarro's and Cezanne's

and some of the other impressionists - whom he had frequently treated without

a fee - and was as interested in art as he was medicine.

In Auvers Vincent

experienced no further seizures. He made occasional short visits to Paris,

saw Lautrec there once more, and went to the Salon and exhibitions, but

he could not take much of Paris at a time. In Auvers he painted constantly.

Dr. Gachet was a miracle of encouragement. But Vincent feared a recurrence

of the dreadful experiences in Arles and Saint-Remy. His consciousness

of the burden his life imposed on his brother was extreme, exaggerated

now because Theo had married and had just had a son.

Vincent

had come to Auvers in May. Near the end of July he began a letter to Theo

in which two sentences are particularly revealing of the nature of his

art and his relationship to it:

"Really, we can speak

only through our paintings.

"In my own work I am risking

my life, and half my reason has been lost in it."

He did not

finish the letter. It was not a "suicide note," although parts of it are

a summation of his relationship with Theo and have about them an air of

finality. But when he stopped the letter in the middle and went out with

his paintbox and his canvas he might have gone out to paint. The revolver

with which he shot himself was never identified. He might have barrowed

it on the way from a peasant, with the excuse that he would use it to shoot

at the crows that were a nuisance in the fields. He shot himself below

the heart, but managed to walk back to the inn where he was staying. Contrary

to the circumstances as usually taken for granted, he did not shoot himself

during an attack or in anticipation of one, and during the two days before

he died he was lucid. Theo had been reached, and Vincent died in his arms.

LATER WORK

The bulk

of van Gogh's life work, the paintings that poured out during the two years

and five months between his arrival in Arles and his suicide in Auvers,

must be more familiar to a wider public today than the work of any other

single painter. At least this is true in the United States. There are individual

paintings such as Whistler's Mother and the Mona Lisa. The Blue

Boy and a Corot or two, that are better known, but in Vincent's case

it is not a matter of one or two paintings. Half his work must have been

reproduced in tens of thousands of color prints, offered in portfolios

as inducements to subscribe to newspapers, framed up assembly-line fashion

for sale in department stores and drug stores. To a vast audience on the

fringe of "appreciation" he is synonymous with modern art -- to which,

actually, he is an excellent introduction.

This

does not sound like a tragic art. Tragic art does not appeal to tens of

thousands of people as living-room decoration. Most of the pictures are

genuinely happy ones unless the pathetic associations of the painter's

life are grafted onto them.

An extreme

flatness as far as modeling in light and shade is concerned, or even as

far as the breaking of color is concerned, is characteristic of the Arles

pictures in general, but their surfaces are heavily textured. The background

of L'Arlesienne is a solid yellow, the brilliant yellow that obsesses

Vincent

now, broken only by the texture of the broad, thick, application Purple,

its complementary, is played against it in the dress, and within the clash

of the two colors the figure is transfixed.

Vincent

now, broken only by the texture of the broad, thick, application Purple,

its complementary, is played against it in the dress, and within the clash

of the two colors the figure is transfixed.

Madame

Ginoux, a neighbor who posed in regional costume for L'Arlesienne,

(left) was one of several friendly people who solved for a while van Gogh's

perpetual model problem. The most obliging of these were the postman Roulin

and his wife. He painted five portraits of Roulin, one of them showing

his uniform in a strong blue against a pale background, with the beard

in short, straight, springing strokes

of

brownish and yellowish tints flecked with bits of bright blue and red.

The figure is more three-dimensionally modeled than that of L'Arlesienne,

but in the remarkable portrait of Madame Roulin called La Berceuse

the flatness is again extreme.

of

brownish and yellowish tints flecked with bits of bright blue and red.

The figure is more three-dimensionally modeled than that of L'Arlesienne,

but in the remarkable portrait of Madame Roulin called La Berceuse

the flatness is again extreme. The

picture began with a sentimental idea. It was to recall lullabies to lonely

men, Vincent said, and he compared its colors to common chromolithographs.

The

picture began with a sentimental idea. It was to recall lullabies to lonely

men, Vincent said, and he compared its colors to common chromolithographs.

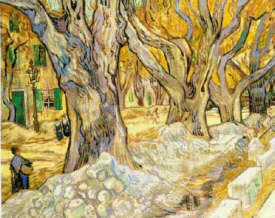

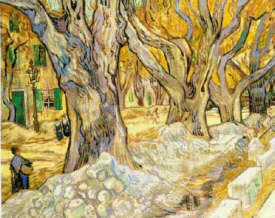

After

the crisis of his first attacks, his break with Gauguin, and finally his

transfer to the asylum at Saint-Remy, Vincent's paintings take on the swirling,

tempestuous form and the more mystical expression of which The Starry

Night is a climatic expression. But they are interspersed with milder

expressions, such as The Road Menders, where the warm tones and

the everyday subject modify and even for a moment conceal the compulsive

writhing of the great trees.

In the

case of van Gogh, the compulsion to paint is inescapable. anyone can accept

the idea that painting is an emotional release for a man who fits in nowhere

else. Since Vincent's time the idea has even been so abused that art schools

are filled with students whose only qualification as potential artists

consists of a demonstrated lack of qualification for being anything else.

What a shame that this too is part of Vincent's legacy.

BACK TO HOME PAGE

E-Mail: [email protected]

Modern expressionism stems directly from the tragic Dutchman, Vincent van

Gogh (1853 - 1890), a man a little older than Georges Seurat, who died

a year before Seurat did. Both stemming from impressionism, these contemporaries

could hardly be more unlike - Seurat with his calculation, his method,

his deliberation, van Gogh with his passion, his shattering vehemence.

Modern expressionism stems directly from the tragic Dutchman, Vincent van

Gogh (1853 - 1890), a man a little older than Georges Seurat, who died

a year before Seurat did. Both stemming from impressionism, these contemporaries

could hardly be more unlike - Seurat with his calculation, his method,

his deliberation, van Gogh with his passion, his shattering vehemence. Instead of La Grande Jatte (see Seurat), so cool, so defined, so

self contained, van Gogh gives us The Starry Night, where a whirling

force catapults across the sky and writhes upward from the earth, where

planets burst with their own energy and all the universe surges and pulsates

in a release of intolerable vitality.

Instead of La Grande Jatte (see Seurat), so cool, so defined, so

self contained, van Gogh gives us The Starry Night, where a whirling

force catapults across the sky and writhes upward from the earth, where

planets burst with their own energy and all the universe surges and pulsates

in a release of intolerable vitality.

"I

have tried to make it clear how these people, eating their potatoes under

the lamplight, have dug the earth with these very hands they put in the

dish....I am not at all anxious for everyone to like or admire it at once."

"I

have tried to make it clear how these people, eating their potatoes under

the lamplight, have dug the earth with these very hands they put in the

dish....I am not at all anxious for everyone to like or admire it at once."

But

now when he paints the Factories at Clichy he has stopped seeing

and thinking in terms of oppressed workers, blackened

chimneys, belching smoke, piles of cinders and slag, and sees instead a

blue sky, red roofs, a foreground of slashing yellows and greens,

all singing in the open air.

But

now when he paints the Factories at Clichy he has stopped seeing

and thinking in terms of oppressed workers, blackened

chimneys, belching smoke, piles of cinders and slag, and sees instead a

blue sky, red roofs, a foreground of slashing yellows and greens,

all singing in the open air.

But

Pere Tanguy suddenly lives, as no other of Vincent's images had

lived until then, and Vincent himself suddenly lives as a fulfilled painter.

But

Pere Tanguy suddenly lives, as no other of Vincent's images had

lived until then, and Vincent himself suddenly lives as a fulfilled painter.

qualifications

for this special case since he was a friend of Pissarro's and Cezanne's

and some of the other impressionists - whom he had frequently treated without

a fee - and was as interested in art as he was medicine.

qualifications

for this special case since he was a friend of Pissarro's and Cezanne's

and some of the other impressionists - whom he had frequently treated without

a fee - and was as interested in art as he was medicine.

Vincent

now, broken only by the texture of the broad, thick, application Purple,

its complementary, is played against it in the dress, and within the clash

of the two colors the figure is transfixed.

Vincent

now, broken only by the texture of the broad, thick, application Purple,

its complementary, is played against it in the dress, and within the clash

of the two colors the figure is transfixed.

of

brownish and yellowish tints flecked with bits of bright blue and red.

The figure is more three-dimensionally modeled than that of L'Arlesienne,

but in the remarkable portrait of Madame Roulin called La Berceuse

the flatness is again extreme.

of

brownish and yellowish tints flecked with bits of bright blue and red.

The figure is more three-dimensionally modeled than that of L'Arlesienne,

but in the remarkable portrait of Madame Roulin called La Berceuse

the flatness is again extreme. The

picture began with a sentimental idea. It was to recall lullabies to lonely

men, Vincent said, and he compared its colors to common chromolithographs.

The

picture began with a sentimental idea. It was to recall lullabies to lonely

men, Vincent said, and he compared its colors to common chromolithographs.