Leger was born in Normandy where he worked

for an architect from 1887 to 1889 and worked as a draftsman in

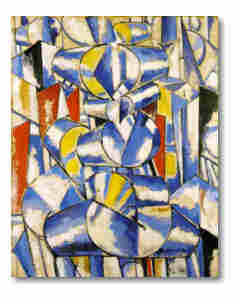

Paris until 1903, when he decided to study painting. By 1909 he

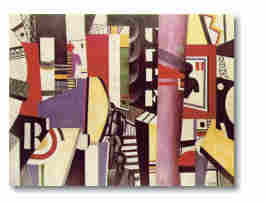

was experimenting with the compositional principles of Cubism,

although he preferred curvilinear configurations to the angular

forms of Braque and Picasso. After being gassed during the First

World War, Liger returned to Paris ,became associated with the

purist ideals put forward by the architect Le Corbusier, and for

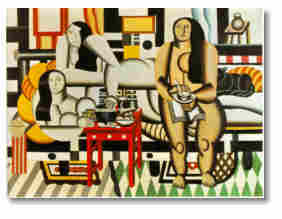

a time painted machinelike images in rudimentary colors. Leger's

interest in social ideals soon brought him to deal with the human

figure in an urban environment, in a vigorous style that incorporated

the tubular forms, condensed spaces, and Monumental scale of his

earlier period. He spent the Second World War in the United States,

where he taught and where he painted groups of cyclists, and then

returned to France. Liger's powerful imagery and his use of bright,

flat colors strongly influenced both graphic designers and fine

artists in the United States and Europe.

LEGER'S THOUGHTS

ON ART

"The feat of superbly imitating a muscle, as Michelangelo did, or a face, as Raphael did, created neither progress nor a hierarchy in art. Because these artists of the sixteenth century imitated human forms, they were not superior to the artists of the high periods of Egyptian, Chaldean, Indochinese, Roman, and Gothic art who interpreted and stylized form but did not imitate it."

"On the contrary, art consists of inventing and not copying.

The Italian Renaissance is a period of artistic decadence. Those

men, devoid of their predecessors' inventiveness, thought they

were stronger as imitators-that is false. Art must be free in

its inventiveness, it must raise us above too much reality. This

is its goal, whether it is poetry or painting. The plastic life,

the picture, is made up of harmonious relationships among volumes,

lines, and colors. These are the three forces that must govern

works of art. If, in organizing these three essential elements

harmoniously, one finds that objects, elements of reality, can

enter into the composition, it may be better and may give the

work more richness. But they must be subordinated to the three

essential elements mentioned above.

Modern work thus takes a point of view directly opposed to academic

work. Academic work puts the subject first and relegates pictorial

values to a secondary level, if there is room."

"For us others, it is the opposite. Every canvas, even if

nonrepresentational, that depends on harmonious relationships

of the three forces-color, volume, and line-is a work of art."

"I repeat, if the object can be included without shattering

the governing structure, the canvas is enriched.

Sometimes these relationships are merely decorative when they

are abstract. But if objects figure in the composition-free objects

with a genuine plastic value-pictures result that have as much

variety and profundity as any with an imitative subject. "

[1950]

INTRODUCTION WHAT ART IS SPIRIT OF ART REFLECTIONS BY ARTISTS MY WORKS OF ART