|

TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION IN PRIMARY CARE |

|

|

MARIA DEL PILAR YAG�E, R.N.

|

|

|

TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION IN PRIMARY CARE

A depressed (sad) mood is a normal reaction to disappointments or losses. A sad mood is not to be confused with major depressive disorder, one of several forms of clinical depression, which is a serious medical condition with major public health consequences. About 15 percent of the general public will suffer from major depressive disorder sometime in their life, but the disorder will be accurately diagnosed and treated in fewer than one in three. A person with major depressive disorder suffers intense mental, emotional, and physical anguish, and substantial disability. The depression disrupts family, job, and social functioning. Depression worsens the prognosis for other general medical illnesses. The worst consequence of untreated major depressive disorder is suicide.

Depression is viewed by many patients and the lay public as evidence of a character

defect or lack of will power. Thus, those with major depressive disorder must endure the

additional burden of having an illness that society views as the reflection of an inherent

personal weakness or fault. The practitioner should be sensitive to these issues, provide

support, and become a patient advocate. In many cases, the diagnosis and treatment of major

depressive disorder can be successfully accomplished by primary care practitioners. When

psychotherapy is called for, it may be conducted in either a primary care or specialized

setting, depending on the availability of a trained, competent therapist. The primary care

practitioner should emphasize to the patient, who is already suffering inappropriate guilt, that

major depression is a medical condition that can be successfully treated. Guideline Highlights

The following step-wise process can assist primary care practitioners in detecting, diagnosing, and treating major depression.

Surveys consistently show that 6 to 8 percent of all outpatients in primary care

settings have major depressive disorder; women are at particular risk for depression.

Although sadness is frequently a presenting sign of depression, not all patients complain of

sadness, and many sad patients do not have major depression. Common complaints of

patients in primary care settings with major depressive disorder include:

The clinician should be doubly alert to the likelihood of depression in individuals under age 40.

Additional clinical clues that raise the likelihood of a major depressive disorder include:

For major depressive disorder, at least five of the following symptoms are present during the same time period, and at least one of the first two symptoms must be present. In addition, symptoms must be present most of the day, nearly daily, for at least 2 weeks.

All depressed patients should be assessed for the risk of suicide by direct questioning about suicidal thinking, impulses, and personal history of suicide attempts. Patients are reassured by questions about suicidal thoughts and by education that suicidal thinking is a common symptom of the depression itself and not a sign that the patient is "crazy."

lists the risk factors associated with completed suicide.

If suicide is a distinct risk (specific plans, or significant risk factors exist), consult a mental health specialist immediately. The patient may need specialized care or hospitalization.

A small percentage of patients with major depressive disorder have bipolar illness. These patients experience mood cycles with discrete episodes of depression and mania. In between episodes, they may feel perfectly normal.

For mania, at least four of the following symptoms, including

the first one listed, must be present for a period of at least 1 week.

Many patients are aware of only some symptoms and may minimize their disability. Interviewing someone who knows the individual well (a spouse, close friend, or relative) can be extremely valuable in obtaining an accurate picture of the patient's symptoms, degree of disability, and course of illness.

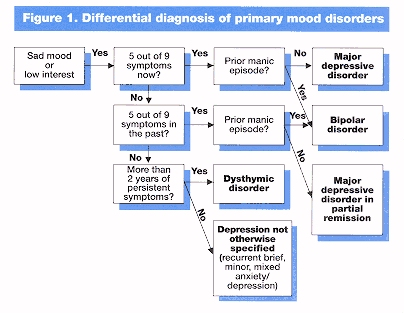

The patient's initial complaints should be evaluated thoroughly with a medical review of systems and a physical examination. If no cause or associated factors can be found for the initial presenting medical complaint, diagnose the patient for a primary mood syndrome.

Too much alcohol, use of illicit drugs, or abuse of prescription

medicines can cause or complicate a major depressive episode. In most cases, once

the substance has been discontinued, the depression lifts

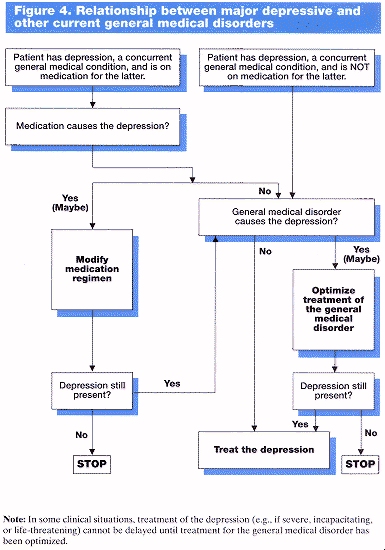

Depression may be an idiosyncratic side effect of many medications. However, the clinician should be aware that this effect is uncommon and usually occurs within days to weeks of starting the medication. Current evidence clearly implicates only reserpine, glucocorticoids, and anabolic steroids with the de novo development of depression as a potential side effect of the drug. Changing to a different medication often relieves the depression (Figure 4).

Depression can occur in the presence of another general

medical condition (Figure 4) (most commonly, autoimmune, neurologic, metabolic,

infectious, oncologic, and endocrine disorders, among others). There are several

possibilities in such cases:

The general medical disorder biologically causes or triggers a depression; for

example, hypothyroidism can be accompanied by depressive symptoms. In this case,

treat the general medical disorder first.

The general medical disorder psychologically results in depression; for

example, a patient with cancer may become clinically depressed as a reaction to the

prognosis, pain, or incapacity, although most patients with cancer do not suffer a

major depressive episode. In this case, treat the depression as an independent disorder.

The general medical disorder and the mood disorder are not causally related.

In this case, treat the depression.

These generally include eating

disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and some cases of panic disorder (Figure 3).

When generalized anxiety disorder co-exists with major depression, treatment

should be directed toward the major depression first.

If panic disorder is present only during major depressive episodes, the major

depression is treated first.

If panic disorder and major depression are both present and the panic disorder

has been present without episodes of major depression in the past, the clinician must

judge which is the most significant condition (e.g., by family history, the level of

current disability attributable to each, and the prior course of illness) and treat that

condition Figure 3. Relationship between major depressive and other current psychiatric

disorders.

If a "personality disorder" is suspected, the major depressive disorder is treated

first, whenever feasible.

It is important to differentiate a normal grief reaction from depression.

A normal grief reaction persists for 2 to 6 months and improves steadily without

specific treatment. Most grief reactions do not meet criteria for a major depressive

episode. Grief reactions are usually seen by patients as normal and appropriate. While

unpleasant, they rarely cause significant and prolonged impairment in work or other

functions. Some individuals experience symptoms of depression along with the grief

reaction. If the major depressive episode persists for more than 2 months after the

loss, a major depressive disorder should be diagnosed and treated.

If the depression persists after treatment of the associated psychiatric general medical, or substance abuse disorders, the

derpession should be diagnosed and treated.

If the mood disorder is still present, or if associated conditions do not exist, work with the patient to treat the primary mood disorder.

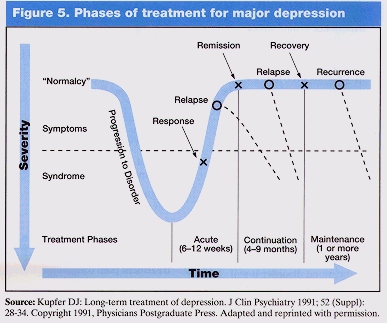

Treatment of depression consists of three phases (Figure 5):

The objective of treatment is for the patient to reach a sustained asymptomatic state.

Figure 6

The effectiveness of any treatment rests on a cooperative effort by

patient and practitioner. The patient should be told of the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment

options, including costs, duration, and potential side effects. In presenting patient and family

education in the clinical management of depression, it is useful to present the following

information:

The aim of acute phase treatment is

symptom remission. Treatment of depression in the primary care setting includes:

The choice of treatment modality is based primarily on the history of illness and the severity

of the major depressive episode. The following general definitions may be helpful in

determining an appropriate treatment:

Scientific evidence indicates that over 50 percent of depressed outpatients who begin

treatment with antidepressant medication experience marked improvement or complete

remission of their depressive symptoms. Considerations for acute phase treatment with

medication are:

Scientific evidence indicates that several forms of short-term psychotherapy (cognitive,

interpersonal, or behavioral) are effective in treating most cases of mild or moderate

depression.

Other types of psychotherapy may also be helpful in the treatment of major

depressive disorder, although their efficacy has not been evaluated fully, if at all. In

individuals with mild to moderate depressions, time-limited psychotherapies appear equal in

efficacy to antidepressant medications.

Considerations for acute phase treatment with psychotherapy alone include:

Psychotherapy requires the availability of an experienced mental health specialist, such as a

psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, psychiatric nurse, or other professional trained in

psychotherapy.

Combined treatment (medication plus formal psychotherapy) should be considered in various

situations, including:

Primary care providers will find it useful to become familiar with one drug with minimal side effects from

each of the major classes of antidepressants (Tables 2 and 3).

Medications should be individualized to the patient in order to optimize treatment benefit

and lower risk. Factors to be considered include:

Patients at risk of experiencing adverse drug interactions or with other medical illnesses may need lower than recommended dosages. Geriatric patients often require lower dosages of medication, and dosage increments should be made slowly.

Treatment of patients with bipolar disorder while they are in the depressed

phase should be done with knowledge of the risk of inducing mania with antidepressant

medications. Consultation with a psychiatrist may be considered if there is suspicion of

bipolar illness.

Treatment of the patient with psychotic symptoms (hallucinations,

delusions) often involves hospitalization, neuroleptics, or electroconvulsive therapy. A

consultation or referral to a mental health specialist is recommended.

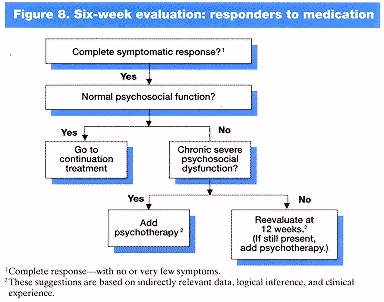

Whether medication, psychotherapy, or a combination are

used, evaluate the patient's response to treatment.

Many patients will respond to an adequate trial of the first drug tried.

Figure 7 summarizes the steps in managing partial or nonresponse to

medication. If inadequate response is a problem, the following steps may be taken:

A significant number (50 percent) of patients with mild to moderate forms of depression

obtain substantial symptom relief with psychotherapy. Many patients begin to feel the effects

of psychotherapy in the first few weeks. Full remission rather than improvement is the

objective of treatment. If there is no symptom improvement at all within 6 weeks, the choice

of treatment modality should be reevaluated. For patients who improve but who are still

symptomatic after 12 weeks, treatment with medication is a strong consideration.

Once the patient has responded to acute phase

treatment with medication, continuation treatment is indicated.

If acute phase psychotherapy

alone was effective, continuation treatment with psychotherapy may be useful in selected

cases.

The aim of continuation treatment is to prevent the return of the most recent

depressive episode (a relapse). The following principles apply:

The goal of maintenance treatment

is prevention of a recurrence of a major depressive episode. The efficacy of maintenance

treatment in preventing a future episode of depression has been clearly demonstrated only

with medication. The following principles apply:

Consult with or referral to a mental health specialist (e.g., psychiatrist,

psychologist, psychiatric nurse, social worker) can be useful in the following situations:

|

|

|

|

Major depressive disorder is a syndrome consisting of a constellation of signs and symptoms that are not normal reactions to life's stress. A sad or depressed mood is only one of the several possible signs and symptoms of major depressive disorder. The clinician may find it useful to provide the patient with a written list of depressive symptoms (pages 3 and 4) and ask the patient to indicate any symptoms experienced. This patient self-report can increase the likelihood of detecting major depression.

Major depressive disorder is a syndrome consisting of a constellation of signs and symptoms that are not normal reactions to life's stress. A sad or depressed mood is only one of the several possible signs and symptoms of major depressive disorder. The clinician may find it useful to provide the patient with a written list of depressive symptoms (pages 3 and 4) and ask the patient to indicate any symptoms experienced. This patient self-report can increase the likelihood of detecting major depression.

Approximately 10-15 percent or more of major depressive conditions are caused by

general medical

illnesses or other conditions (See Figure 2). Generally, the principle is to treat the associated

condition first. If the depression persists after treatment of the associated condition, major

depressive disorder should be diagnosed and treated.

Approximately 10-15 percent or more of major depressive conditions are caused by

general medical

illnesses or other conditions (See Figure 2). Generally, the principle is to treat the associated

condition first. If the depression persists after treatment of the associated condition, major

depressive disorder should be diagnosed and treated.

(Figure 3).

(Figure 3).

presents a flow diagram for the treatment of depression. These principles apply no matter

what treatment is selected. The essential features of this plan include:

presents a flow diagram for the treatment of depression. These principles apply no matter

what treatment is selected. The essential features of this plan include:

The dosage is the same as that used in acute treatment.

Medication visits can be extended to once every 2 to 3 months for most patients.

The dosage is the same as that used in acute treatment.

Medication visits can be extended to once every 2 to 3 months for most patients.