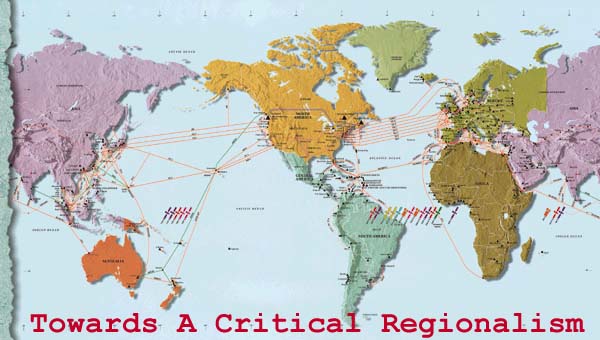

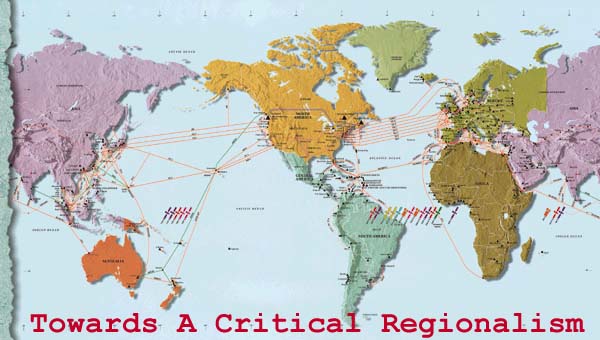

In our bid to leap from an era of primary production and rapid industrialization into the information age, Malaysia has embraced multimedia technology and computer mediated communications. Yet a graphic representation of the network infrastructure of the world reveals the centrality and supremacy of North America in this era of global communications. Further, an assessment of information flows reveals a heavy movement of content out of the United States, in contrast with a less voluminous flow in, consisting mainly of requests. The discrepancy is so great that some solutions to bandwidth problems involve separating down and up traffic.

Indeed, as ubiquitous as they are today, the technologies of the multimedia revolution are laden, as all tools are, with the values of the milieu from which they have emerged. Ismail Zain, has called for a 'critical regionalism' in the face of the 'universalism which is the outcome of instant information'. As early as 1988, while advocating and exemplifying the use of digital media in art, he was insisting that as the consumers of information we should 'adopt a more critical and autocratic posture'. A consideration of the history of' 'multimedia', in this light, yields the basis for an Asian reclamation of the new communications paradigm.

In fact, multimedia is not new. It is only the modernist legacy of the purity of form that makes contemporary, technologically induced convergence appear so revolutionary. Contrary to the reductive interpretations of modern art, the African mask is not mere sculpture but an integral constituent of a multidimensional communal performance tradition. In the Medieval illuminated manuscript, painting and writing can be said to merge on an integrated 'platform'- the book. The Gothic cathedral is a monument to 'convergence' in which stained glass images and sculpture are seamlessly integrated in what is arguably the pinnacle of European architectural achievement. Even the late modernist integration of fine art and performance constitutes a multimedia approach, albeit analog and not digital.

In the course of his study of the Chinese Pien Wen or 'transformation text', Victor Mair has revealed the global development of the ancient tradition of story-telling using pictures. To 'perform' a Pien Wen, the narrator makes use of a 'transformation picture' or a 'turning transformation' (picture scroll). Mair's thesis is that this tradition of picture recitation originated in India, spread to East and West Asia and the Middle East and then on into Europe.

With regard to South East Asia, Java in particular, Ma Huan, secretary to admiral Cheng Ho, writing in the year 1416, notes, 'They have a class of men who make drawings on paper ... for the supports of the picture they use two wooden sticks, three feet in height, which are level with the picture at one end only'. Of the performance of the picture recitation, he observes, ñsitting cross-legged on the ground, the man takes the picture and sets it up on the ground; each time he unrolls and exposes a section of the picture he thrusts it forward towards his audience, and, speaking with a loud voice ... he explains the derivation of this section'.

It is in this integration of 'painting and performance' - wayang beber in Java, par in Gujarat, etoki in Japan, parda-dar in Iran and so on, that we will find the roots of a multimedia tradition of our own. Indeed, those who are accustomed to standing before their notebooks while enunciating their ideas with the aid of 'powerpoint' projections, will empathise with the argument that the Asian picture recitation is the primordial form of multimedia.

Perhaps, it is

in this tradition of painting and performance that we will find the basis

for Ismail Zain's ïcritical self-consciousness' and the 'requisite

conceptual efficacy' to deal with the new technological situation on our

own terms. It is essential that we engage with the pressing critical and

theoretical issues that are latent in the new

technology so that we can stake our claim

on convergence. Instead of being overwhelmed by the inflow of Western values

via supposedly value-neutral technologies, we are in the position to approach

the new tools critically, and to deploy them in the service of a cultural

transformation conceived on the basis of our own traditions and our own

needs.