[Home] [General Reader/More info] [How to sex chicks] [FAQ][Order Now!]

[About the author]

Essay No. 1 (April 2001):

The Development of Artificial Incubation of Eggs

By R. D. Martin

Essay Contents:

The Early Egyptian incubators of some 3,000 odd years ago were a series of mud brick egg ovens type rooms built each side of a central passageway all within a large mud brick building or hatchery if you like. A similar set-up if you think about it to today's modern mammoth hatchery with its incubator rooms each side of a long room or passageway.

Thousands of eggs were placed in heaps on the floor of each incubator room. In the upper chamber of the room, there were selves for low burning fires of straw, camel dung or charcoal to provide radiant heat to the eggs below. The entrance to each incubator room from the passaway was through a small manhole.

Temperature control was achieved via the strength of the fires, jute covers over the manholes and regular openings of vents in the roof of the ovens and passaway. Humidly was controlled by spreading damp jute over the eggs as necessary. The roof vents also allowed smoke and fumes from the fires to escape and provide some light.

The piles of eggs were rearranged and the eggs turned twice a day. The middle passaway also served as a warm brooding area for the chicks when they were hatched.

The amazing thing about all this was that the temperature, humidity and ventilation were checked and controlled without using measuring devises or gauges, nor were there any thermometers. They achieved all this by having the hatchery manager and the hatchery workers actually living inside the hatchery building. By living in they were able to detect any departures from the norm, human thermometers. If you think about this they would soon learn to judge the humidity, temperature and air freshness by their own feeling and their sense of touch. It is also recorded they tested the temperature of the eggs by holding the egg against their eye lid, the most sensitive part of the body for judging temperature.

The Egyptian hatchery methods were jealousy guarded as trade secrets ad handed down from generation to generation within certain families in a monopoly situation. Local farmers brought their fertile eggs to the hatchery. The hatchery owner was required by law to return two chicks for every three eggs received, the surplus chicks providing his remuneration. Looking at these figures the hatchery would need to get somewhere near 75% hatches or better to make a living after other costs were met.

Millions of chicks were produced by these hatcheries every year, so that Egypt must have had a reasonably organized poultry industry. The warm and fairly constant temperature in Egypt helped make their method successful. In contrast to some of the stories my former chick sexing colleagues used to tell me when they were engaged to sex chickens in Europe after the second World War: on several occasions the hatching eggs had become frozen while waiting to be placed in the incubators. At one hatchery during a power failure the eggs became so cold while in the incubators that several weeks hatchings were ruined, much to the dismay of my chick sexing colleagues who had travelled so far for a 14 week chick sexing season.

By the mid 1600's Europeans had bought Egyptian experts to Europe to build and operate an Egyptian type hatchery, but they were not successful and the project was abandoned. After hearing of the experiences of my colleagues above it is not too difficult to imagine why these Egyptian incubators did not work in European conditions

Similar mud brick hatcheries still operate in Egypt to this day, still using the old methods and old trade secrets.

Late in the 1750's a famous French researcher into artificial incubation, de Beaumur, said that Egypt should be more proud f her incubators than her pyramids. Aristotle, the Greek philosopher, writing of poultry in about 400BC, describes a similar method to Egyptian incubators, but where burying them in mounds of decomposing manure provided the heat to the eggs. As late as 1875 an incubator based in piles of decomposing manure was granted a United States patient.

In Australia there are Megapodes, which include Mallee fowl and bush turkeys that incubate their eggs from natural heat in a mound of warm sand and rotting vegetation. Additional heat is provided to the mound by the sun. Each day the male Mallee fowl opens up the sand nest tests the eggs with his tongue, then regulates the temperature by placing more or less sand and compost cover on to the eggs.

Artificial incubation of eggs was practiced in China as early as 246 BC and their methods eventually spread through South East Asia.

As in Egypt, a heavy walled, insulated mud brick building was used. Inside was a series of mud brick ovens. A charcoal fire was maintained in the base of the oven and was controlled by a damper or cover over the small service opening. The top of the oven was closed in by a very large clay container, which filled the body of the oven, the bottom of which was close to the fire below. The container was half filled with ashes, which became warm. Large straw baskets were placed into the container, in contact with the hot ashes. The eggs were placed in small muslin bags, the bags loaded into baskets and a lid fitted over the top.

Rearranging the bags each day provided the necessary egg turning. Again eggs were tested for temperature against the eyelid of the operator. The Chinese also utilised a system of heat transfer. After the chick embryos developed they started to give off increasing amounts of animal heat, and do not need added heat. By mixing bags of older eggs with the newer eggs, the Chinese utilised this animal heat to warm the new incoming eggs. At 16 days, fowl eggs were removed to another hatching area in the building, where they were just covered with a blanket and allowed to hatch from 19 to 21 days.

The Development of Western Incubators

After the failure of Egyptian incubators in Europe, the pressure was on to develop a more sophisticated mechanical incubator. The French scientist, de Beaumur published in 1750: 'The Art of Hatching and Bringing up domestic Fowls of All Kinds, at Any Time of the year. Either by Means of Hotbeds or That of Common Fire'. De Beaumur used fermentation to heat the incubator, as well as an early type of thermometer.

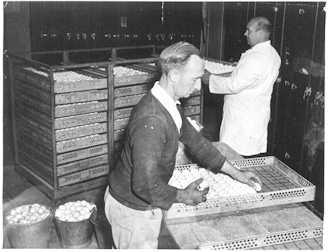

Charlie Bode (white coat) and his assistant, George, setting eggs into the trays of 'Multiplo' incubators.

Over the next 100 years more experimental incubators were produced, some using hot water, some heated by charcoal others by steam. Self-regulating oil or kerosene lamps with a damper were also widely used to heat water and hot air incubators in the second half of the19th century. Very few of these were successful because they were unable to regulate the range of temperature to within the narrow range which was required.

A famous hot air incubator was the American incubator the 'Cypher Incubator'; it used a thermostat and an improved method of heating.

It was the advent of thermostats to regulate temperature accurately which allowed the development of modern incubators. For example in the United States in 1885, there were seven different brands of small 'still air' cabinet incubators for sale. By 1900, there were 24 types available. From 1900 to 1915 about 50 incubators were offered for sale. They were generally small machines designed for small poultry producers with a capacity of less than 200 eggs. Thousands upon thousands were sold.

The years 1929 to the early 1940's was a period of economic depression throughout the world, yet it was during this decade that the poultry industry experienced two events which had a profound influence on the industry's future growth and stability.

The two events were the development of the electric forced draught egg incubator in the early 1930's and the development and introduction by the Japanese of day-old chick sexing.

The larger forced-draught incubators revolutionised the production of day-old chickens not only in the quality of the chickens but also in hatching percentages of eggs set. Up to the development of these forced draught incubators hatching results of around 50 per cent of all eggs set were considered satisfactory. With forced-draught incubators these figures gradually improved till 90 per cent of all eggs set were achieved. The latest mammoth steel cabinet incubators sometimes achieve higher percentages than this. I remember one large broiler hatchery that I used to sex chicken for got up to 98 per cent of all eggs set, maybe this is the norm now.

These improvements in hatching results and later being able to separate the sexes as soon as they were hatched enabled the egg producing industry to expand and to greatly reduce costs.

The first United Stated patents for the new 'forced-draught' incubators were taken out as early as 1911 and 1918, the 15,000 egg 'Petersime Incubator' forced draught incubator was the first 'mammoth' incubator to be heated by electricity. Other famous American incubators in the 1920's and 1930's were the Smith, Buckeye and Robbins. The large forced draught incubators allowed mass production of chicks with very much less labour. The more accurate temperature and humidity controls raised hatchings percentages to 70 to 80 percent of all eggs set. The commercial poultry industry as we know it today was on its way.

A single stage incubator once the eggs are placed in the machine they

saty there until they hatch. It is claimed this method requires less labor.

In Australia the most famous incubator company was the Multiplo Incubator and Brooder Company of Sydney, founded by the Moll family. They started production in 1933 and they were so efficient and successful that many of these machines are still in use today. I had a 10,000 Multiplo and a 5000 Multiplo on my farm, which I sold to a small hatchery at Bendigo and both Machines were still in operation up till 1999. Another Australian incubator was the Gamble Incubator a company owned by G. N. Gamble and Son. It was George Mann who brought out the first Japanese chick sexing experts to Australia in 1934.

During the 20 years from 1960 progress in the poultry industry was extremely rapid throughout the world. It was the period of greatest change in the industry's history. Two outstanding changes occurred. One was the increased size of operations, such as the number of birds that could be reared in a single shed, and the large number of chicks hatched in incubators.

The other great advance was in technology. This was necessary for the new economies of large-scale. Production. By the 1980's the poultry industry was one of the most efficient industries in the world.

A modern mommoth hatching room with its hatchers on both sides, the eggs are wheeled from the settings rooms into the hatchers

There are still a few small hatcheries operating in Australia, but with the advent of corporate agriculture, a few large companies now dominate chick hatchings in Australia. The world situation has a similar pattern. Hatcheries are great technological wonders. The smallest incubators would contain at least 70,000 eggs Electronic controls regulate temperature to within o.1c, automatic humidifiers control moisture, eggs are turned automatically 24 times a day. Temperature, relative humidity and other information is provided by digital display outside the incubator. The complete operation can be computer controlled, including all alarm systems. All hatchery staff have to shower before entering the hatchery section. Even my 'poor' former colleagues, the chick sexers, have not escaped all this technology.

The chick sexers throw their chickens into chutes, which count the chickens by infrared sensors. This gives the speed and percentage split of the pullets and cockerels of individual sexers and as a group, which is displayed on a computer behind the checkers who are checking on the accuracy of the sexers working outside on the perimeter of the sexing station. Glancing at these sexing stations the chick sexers at first glance appear to be part of the machinery. No individual sexers here, long gone are the days when the accuracy of most chick sexers were known by most people in the industry, in fact many of the small hatcheries in Australia made their name in chick sales on the accuracy of their chick sexer.

A chick sexing station which holds up to 18 chick sexers around the perimeter and 2 to 3 chickers inside the circle who check the accuracy of those working in the perimeter outside.

The Poultry Fancier

Looking back over what I have been writing about the 3000-year history of the incubation of eggs I am reminded of that bit of philosophy that states 'everything changes, nothing changes'. Are modern day hatcheries that different in layout to those early Egyptian mud brick hatcheries? Their percentage of chickens to eggs set must have been much better than what was achieved on the still air incubator discussed above, other wise the hatchery operations would not have made any profit.

I started in the poultry business with a few hens and a rooster in my parent's back yard in a suburb of Melbourne. My uncle used to take me to the poultry shows and meetings of the poultry club that he was a member. Some fifty years later I again came into contact with Poultry Fanciers through my stall at the Show Ground during the Royal Melbourne Agriculture Show. The Poultry Fanciers are still the same as they were in my childhood, friendly and proud of their birds, always willing to discuss and give advice about poultry breeding. The present day broiler industry owes a debt to these poultry fanciers who have kept the various breeds true to type and so supplying breeders for the present day broilers stock.

Poultry Fanciers are still very active in Australia and my little research on the Internet seems to indicate that they are also active in other parts of the world also. In Australia hobbyist and fanciers are still well catered for by local manufacturers of small incubators who use some of the new electronic technology.

There is a saying, 'once a poultry farmer, always a poultry farmer'�I would not argue with this.

References and acknowledgements:

- 'The Carter Family of Werribee' by W. M.S. Carter. Corporate Printers. Melbourne.

- 'The Victorian Poultry Journal' copies dated 1 Aug. 1928 to 1 Dec. 1939. 'Australasian Poultry' August/September 1990. Poultry Information.

- 'The Specialist Chick Sexer' by R.D. Martin. 1995. Bernal. Melbourne.

- 'The Modern Encyclopaedia Illustrated' Oldham's Books London.

- My own uncatalogued and disorganized notes collected over a lifetime of being a poultry fancier, poultry farmer & hatchery man and a chick sexer.

Acknowledgments to my friend of 40 odd years Bill Stanhope. Former Principal Poultry Officer of Victoria, poultry farmer and Assistant Editor 'Australasian Poultry'. And also conversations I have had with commercial chick sexers in USA, UK and Japan.