A letter from the Duck Man

From the correspondence of Carl Barks, compiled by Geoffrey Blum

Well! A fan! Most happy to hear from you, suh! It's gratifying to know I have readers who like my stuff well enough to become fans. Most of my readers started on Disney comics as kids and have continued to this day. Among them are scientists, artists, advertising men, and college professors. So far not one has been a bank robber.

Well! A fan! Most happy to hear from you, suh! It's gratifying to know I have readers who like my stuff well enough to become fans. Most of my readers started on Disney comics as kids and have continued to this day. Among them are scientists, artists, advertising men, and college professors. So far not one has been a bank robber.

Your letter with its account of your complex deals in assembling a collection of Duck comics is very interesting. I am not a collector, so the thuggery and humbuggery that is part of the collecting business is all mysterious frenzy to me. When is the fad going to shift to some other favorite? Perhaps Bugs Bunny comics will be the gold mines of next year. Too bad I didn't foresee

some of the demand for my early comics. I gave away a fortune back in the forties and fifties.

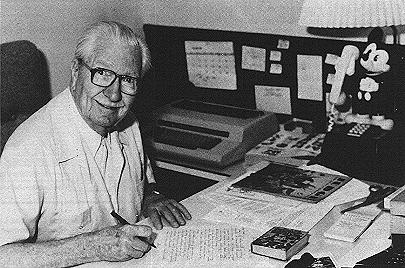

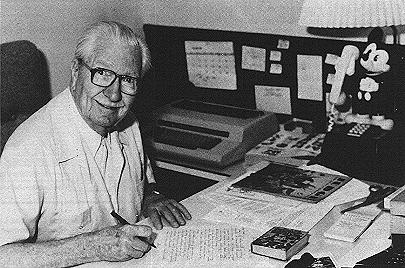

You ask about myself, perhaps figuring the personality and background of a writer colors his product. Could be, although some of the stuffiest prigs I ever saw wrote some of the jazziest material. I am 83 wheezy years old and don't look a day over 82 1/2. In personal background

I am a backwoods bumpkin. My people were wheat ranchers in sagebrushy eastern Oregon. What a windy, dusty, profitless life! I left that area in the early twenties and have been back there only briefly in the years since.

I had no college training. My education consists of eight grades in a one-room Oregon schoolhouse. But schools was GOOD in them days, son! I've traveled nowhere, seen few movies or plays, read few books (e.g. Zane Greys and Perry Masons). The background research evident in my comic book stories was laboriously dug out of my shelves of National Geographic and Encyclopaedia Britannica. I've long been afflicted with partial deafness, so I've missed any oral exchanges with people whose ideas might have broadened my intellect. But I am interested in practically everything, which probably accounts for the wide range of adventures which befall Uncle Scrooge and the Ducks.

On the physical plane, my experiences during my early years, when I worked as a farmer, logger, riveter, muleskinner, pseudo-cowboy, and printing press feeder, always terribly inefficiently, gave me practical knowledge for complicating many of Donald Duck's problems. The perversity of beasts, machines, and nature I knew by heart.

When did I begin drawing? In childhood. I first copied such stone-age comic artists as Winsor McCay and Opper. Always was inclined to invent my own comic faces, figures, and scenes. What I copied from the cartoonists of my day was their technique of pen handling and shading.

At about age 15 I subscribed to the old Landon School mail-order course in cartooning. I never finished the course, because World War I was in the air, and a teenager could earn five dollars a day in the hayfields. But the thorough basics outlined in those few Landon lessons have been the foundation beneath my whole concept of dramatic and humorous presentation.

Most of what I know about drawing I taught myself. I learned to draw cartoons well enough to sell by imitating drawing styles that caught my fancy, but I fully agree with the expression that he who teaches himself has a stupid professor. Any kid who thinks art schools don't help a beginner needs his head replaced.

In the early thirties I sold cartoons to the Calgary Eye-Opener, a risque humor magazine in the Whiz-Bang format. Your granddad might remember Whiz-Bang. Them was the days when drawing was fun! Also sold a couple of cartoons to Judge. Your granddad would

surely remember that hip old slick humor magazine that was in every dentist's waiting room.

I got 90 bucks a month from the Eye-Opener, which was for writing and drawing more than half the book, editing it, and composing stalling letters to contributors to gloss over the fact that no money was in the bank to pay for their stuff. Free-lancing and work on the Eye-Opener kept me out of the bread lines until 1935, when I got on at the Walt Disney Studio. There, as part of my training, I had to attend art classes several hours a week for several months.

I worked for seven years in Disney's story department, where we drew very rough sketches with big pencils for the storyboards. Needless to say, I was a "duck man." I learned much from the way we had to polish and repolish our scenarios in the old Donald Duck animation shorts. Plots had to build, and climaxes had to crackle. We had to stage gags with characters so paced and so expressively emoting that viewers could grasp the whole idea in fractions of a second. Some of that spit and polish may still be rubbing off on my work.

The grind was terrific. My leaky sinuses wouldn't take the air conditioning. I got wind that Western Printing and Lithography was in need of stories and art for original Disney comics, so I did a little art for them while still in the Studio. My first comic book work was for "Donald Duck finds Pirate Gold" in 1942. That was the first of the full-length Donald Duck adventures.

I took a chance, quit Disney, and moved to the San Jacinto desert to dry out my sinuses and raise chickens. Luckily I caught on quick with Western. I started to do them a few Donald Duck ten-page stories in my spare time and was soon so swamped with work, I gave up the chickens and went into full-time Duck production. My first full-length story-and-art combo was "Donald Duck and the Mummy's Ring" in 1943.

I was a loner, working in a small town far from any contacts with other comic bookers. I wrote my scripts in pencil. Each page was broken down into panel notations of scene, characters, and dialogue. This script was never sent to the editors. I started drawing the story with no-one's

okay but my own. (What a change from my years in the Disney Studio Duck story unit!)

My drawing paper was about two-and-a-quarter times the size of the printed page. I drew direct on the sheet with a blue pencil, then inked the drawings. You ask if I had another artist working with me. Yes - my wife. During most of the last dozen years, she inked the dialogue, drew backgrounds such as countless vats of diamonds and bins of money, and painted in all the solid blacks and shading. Prior to 1953, I did all my own drawing.

The drawings were usually mailed to the Los Angeles office of the publishers, and soon a check would plop into my mailbox. I had virtually no trouble with the editors, because I was tooth-chatteringly careful about what I produced. Very seldom during the years did parts of a story come back for changes, which is fortunate, for I was of a sour-puss temperament that blew my marbles in all directions at the first hint of having to do anything twice.

As for pay, I got about average for the industry. In reply to your comment that I must have had much fulfillment from my work, I'll say that I fulfilled everything except my wallet.

The variations you see in the duck's appearance over the years are due to trying to keep him looking like the screen duck, whose appearance changed radically. Other changes were caused by switching the grade of paper I drew on. My best work has always been on Strathmore medium surface. In the old days I was furnished with Strathmore, and my style was more detailed and the

characters more expressive. Then along in the middle fifties the office got on a money-saving kick and began furnishing us artists with a clay-coated import from Germany. The pencil and pen dug into the surface and couldn't be guided with any finesse. The result was a tightening of the lines, less bounce to the characters. I griped, but the economy of the cheaper paper won out in the front office.

I didn't originate Donald, Daisy, or Grandma Duck. However, the nephews and Gus Goose first saw the light of day in the duck story unit in which I worked at the Studio. I invented Uncle Scrooge, Gladstone Gander, Gyro Gearloose, Magica de Spell, Flintheart Glomgold, and the Beagle Boys while working for Western Publishing. These characters were created to fill specific needs in certain stories. I hardly expected ever to use them again, but their special type did become useful. Uncle Scrooge especially kept developing new outshoots of character like a tree growing and unfolding leaves of thousand-dollar bills.

My firm resolve in the Duck stories was to keep off the shopworn cops-and-robbers kick that depraves so much of TV and other mediums these days. As a result, my gimmicks have usually dealt with human frailties like greed, pride, and arrogance. A kid long ago told me that he liked the stories because he never knew when he picked up the magazine whether Donald was going to be a hero, a villain, a windbag, or a heel. I seldom knew myself until well along with the writing of each story. Then, when I needed that "extra something" that would give the story a reason for existing, I'd tag the duck with a character. Squares call that extra something the moral.

Your mention that my stories are frequently satirical sent me to the dictionary. I realize after reading the definition for satire that you're right. I can assure you that it's been an outright accident. I was incapable of writing much in the way of hidden messages into my stories.

I guess I found it natural to satirize the yearnings and pomposities and frustrations of the ducks because of my early contacts with people in the rougher walks of life. The cowboys, ranchers, loggers, and steel workers with whom I worked before I broke into the "soft" field of

cartooning were all satirists. They had the ability to laugh at the most awesome miseries. If they hadn't seen humor in their hard-bitten lives, they'd have gone crazy.

One thing I should make clear. I was writing escapist entertainment. The plots that so often featured the "far away and long ago," as a Boston fan expressed it, were staged in those areas and times because they took the reader out of his present world. Archaeology is interesting to practically everybody, and I was striving to get the atmosphere of ancient cultures and places into my stories, also the old lost treasure gimmick that is forever popular with kids.

The comic books of the "golden years" of the forties, fifties, and sixties were all escapist reading in my opinion. The kids who read Superman, Plastic Man, and Tales from the Crypt were all taking a trip. The fad for that form of escape is now almost defunct. Comics have been replaced by pot.

Recently a fan sent me J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. These books are my first sample of Fantasy Fiction. I never read Alice In Wonderland, Grimm, or Hans Christian Andersen. And to find that Tolkien deliberately slants the stories at adult readers makes me do a double-take. Yet he repeatedly stresses the point that his Hobbits are creatures of fantasy. Somehow I'd gotten the idea that Fantasy Fiction was for kids only, and that Science Fiction was the type that authors slanted at adults.

An odd coincidence has happened. My wife just now brought a fan letter from the post office. It's from a guy in Seattle. Here is a quote from the letter: "Those long one-shots about Donald and Scrooge [stir] that 'sense of wonder' that is missing in most fantasy fiction."

Get that fantasy fiction. Here's another quote: "You created a fine world of fantasy - yet the adult humor through it made it realistic, too. And the faults of your

characters made them lovably human."

Get that fantasy... adult humor... lovably human. I've always looked upon the Ducks as caricature human beings. Perhaps I've been years writing in that middle world that J.R.R. Tolkien describes, and never knew it. Anyway, I'll be watching author Tolkien as I read his involved stories. What a world he has created, and all without the use of self-important homo-sapiens. I suspect that somewhere he'll slip in a line that shows he really is writing about caricatured human beings.

I hope that the stories you have read in the Duck and Scrooge books have helped to give you a broader understanding of life, as well as entertainment. I always tried to write a story that I wouldn't mind buying myself. In my attempts to make my comics worth 10c or 12c or 15c I seem to have produced some passages that were even worth remembering. If more of my readers grow up to sit in the Senate chamber than to sit in the gas chamber, I'll have been richly rewarded for trying to turn out a good product.

No, I don't have any more sketches to sell at the present time. I'm too busy trying to paint more great "artworks" to even sort out the few old production drawings I have left. Maybe when I retire -

Keep working at the things you like to do. Sometimes they pay off.

Sincerely

Carl Barks

PS.

The comic page you sent from the Tom & Jerry story may have been written or drawn by an artist who knows me. Most Likely, though, "Dr. Barks" was considered a good name for a Doctor of Dogology.

The comic page you sent from the Tom & Jerry story may have been written or drawn by an artist who knows me. Most Likely, though, "Dr. Barks" was considered a good name for a Doctor of Dogology.

No, I don't look like the Dr. in the story. Dogs faint when they see me.

Note from Geoffrey Blum:

My aim in creating this pastiche was to let Barks voice his own reflections on his life and work. Compiling the quintessential Barks letter seemed to be the answer, and there was a wealth of material to hand. In the 1960s, only a small number of Barks enthusiasts had run the master to ground, and he did not yet feel pressured or jaded about his comic book work. Answering fan mail was a treat, and he wrote his correspondents long, reflective replies, though none quite as long as this compilation. To reprint a selection of letters intact would have meant sacrificing several important ones for lack of space. By distilling from many, I hoped to preserve all the choice passages.

In fitting together the parts of this new letter, I strove to preserve Barks' original language. Spelling errors I corrected silently, and I amended punctuation and inserted occasional conjunctions to maintain the writing's flow. Only once, where a bridge between passages was needed, did I interpolate a sentence of my own: "Recently a fan sent me J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings."

To bring the letter up to date, I altered a few tenses and one reference to Barks' age. Only one passage breaks chronological step, because I felt it important to leave it in its original form. As it stands, the letter gives the impression that Barks has just received the Tolkien books and the fan letter about fantasy fiction. Actually, he received them in 1965. To recast his enthusiastic response into the past tense would have destroyed its spontaneity.

I originally intented to footnote every borrowed line, but the piecework became so complicated that notes would have been distracting. A list of sources follows. Except the letter to Donald Ault, from which I took only the dosing line about "working at the things you like to do," all of the following are on file at the Walt Disney Archives.

To Miss Anderson, October 8, 1965 and December 28, 1965

To Donald Ault, September 18, 1970

To Dick Blackburn, March 8, 1968

To R.O. Burnett, December 13, 1960

To Tom Collins, August 15, 1973

To John Coulthard, October 8, 1961

To Bill Craig, May 6, 1966

To Craig Hayes, October 21, 1961

To Larry Ivie, n.d. (October, 1960) and December 11, 1960

To Richard Kravitz, May 16, 1973 and February 11, 1974

To Don Lineberger, October 27, 1972

To Bernie Ostrov, October 16, 1974

To Michael Peak, January 21, 1963

To John Spicer, n.d. (April, 1960)

To Howard Steinbach, February 22, 1975

To Don Thompson, October 18, 1962

To John Verpoorten, December 2, 1960 and July 11, 1961

To Joe Vucenic, n.d. (September, 1960)

To Malcom Willits, January 17, 1962 (P.S. and illustration)

To Malcom Willits, January 17, 1962 (P.S. and illustration)

To Plattsburgh Comics Club, November 11, 1974.

Well! A fan! Most happy to hear from you, suh! It's gratifying to know I have readers who like my stuff well enough to become fans. Most of my readers started on Disney comics as kids and have continued to this day. Among them are scientists, artists, advertising men, and college professors. So far not one has been a bank robber.

Well! A fan! Most happy to hear from you, suh! It's gratifying to know I have readers who like my stuff well enough to become fans. Most of my readers started on Disney comics as kids and have continued to this day. Among them are scientists, artists, advertising men, and college professors. So far not one has been a bank robber.

The comic page you sent from the Tom & Jerry story may have been written or drawn by an artist who knows me. Most Likely, though, "Dr. Barks" was considered a good name for a Doctor of Dogology.

The comic page you sent from the Tom & Jerry story may have been written or drawn by an artist who knows me. Most Likely, though, "Dr. Barks" was considered a good name for a Doctor of Dogology.