APA 1998 PAPER PRESENTATION:

SAN FRANCISCO

Cross-cultural judgments of typicality-abusiveness of abusive behaviors in intimate relationships.

Lin Lim., Mizuho Arai., Boston University

Email: [email protected]

![]() ¶ Home

¶ Home

Introduction

The occurrence of violence in intimate relations has received increasing amounts of attention in the last decades. In a review of research on physical and psychological abuse, Marshall (1994) noted the findings of Vitonza and Marshall (1993) that more than 75% of students had not only expressed but also hold the threats of violence to their partners.

Moreover, Marshall (1994) reported that approximately 55% of the students surveyed had been violent to their partner (excluding sexual acts) and 56% reported having sustained at least one of the violent acts in their dating relationships. Bethke and Deloy (1993) studied the acceptability of dating violence in relation to the seriousness of either the current or past dating relationship, the sex of perpetrator, and the setting in which the violence took place. They found that the more serious the relationship, of the respondents, the more tolerant they were of the abusive behaviors. Moreover, when the hypothetical perpetrator was the female, the respondents were more tolerant of violent behaviors in their dating relationships. Although violent behavior by a hypothetical male perpetrator was judged less acceptable, both male and female respondents reported similar levels of victimization and perpetration in their own dating relationships. Findings from Vitazo and Marshall, Bethke and Deloy, and others such as Bookwala et al (1992) and Bethle and Dejoy (1993), indicate that violent behaviors are used by both sexes. Moreover, it is clear that violent acts against dating partners are accepted or tolerated under certain circumstances. However, these findings on perceptions and levels of violence are from studies conducted within the western culture, and relatively little is known about the factors that influence attitudes towards violent behaviors in intimate relationships in other cultures. The present study examined judgments of typicality and abusiveness of physical, psychological, and verbal abusive behaviors in intimate relationships from a cross cultural perspective.

The respondents were recruited from different ethnic groups- i.e., Caucasian, Japanese, Asian American and Singaporean. These four different ethnic groups were selected because of some similarities and some important differences. Among them, for example, all four groups are industrialized societies, but the American society is characterized as individualistic whereas the Japanese society is characterized as collectivistic (Ho, 1990). Between these two extremes are groups such as the Asian American and Singaporean, which would be characterized as bicultural or multicultural (laFrombise, Coleman, & Gertin, 1993). The purpose of this study was to examine whether American, Asian American, Singaporean, and Japanese students differ in their judgments of the typicality and abusiveness of violence in dating relationships.

In regard to gender differences, there is some evidence that females are more likely to report using and receiving violence in intimate relationships than males (Marshall, 1994). One possible explanation of these findings is that males may underreport and females may over report their own violence. Moreover, Marshall (1994) reported that males are more likely to engage in acts such as hitting or kicking a wall, door, or furniture, grabbing and arm twisting, whereas females were more likely to engage in acts such as throwing an object, scratching, biting and punching. These findings suggest that males and females have different attitudes and orientations towards violence. Therefore, we also examined the possibility of gender difference in judgments of both typicality and abusiveness of abusive behaviors in intimate relationships.

Methods

The sample consisted of 575 participants recruited from introductory psychology classes in a large urban university in Boston, and from the community in both Japan and Singapore. The sample as a whole consisted of 150 Caucasians (27.7%), 176 Japanese (32.5%), 108 Asian Americans (20%) and 107 Singaporeans (19.8%). The mean age for the sample was about 21 years old with 59.1% females (N=339) and 68.7% (N=395) single. Descriptive statistics for the sample broken down by ethnicity are shown in Table 1.

All participants completed a 22-item modified Typicality Scale in addition to a demographics questionnaire. The Malley-Morrison couple-conflict research team at Boston University developed the 48-item, 7 point (Likert) typicality scale in 1994. Malley-Morrison et al. (1994) took behavioral items from Straus's (1979) Conflict Tactics Scale and other abuse scales such as the Shepard and Campbell (1992) Abusive Behavior Inventory and presented them in the context of stressful situations. Items were counterbalanced by sex of perpetrator. This version of the Typicality Scale has sub scales for psychological, physical and verbal abusive behaviors and requests judgments of both the typicality and abusiveness of those behaviors within a husband and wife relationship; the response scales range from 0 (not at all typical/abusive) to 6 (extremely abusive). Examples of items are shown in Table 2.

For purposes of analysis, total typicality and total abuse scores were calculated. By adding up scores on the 22 individual items. In addition, typicality and abusiveness sub scale scores for physical, psychological and verbal abuse were also calculated separately for behaviors perpetrated by the husband and behaviors perpetrated by the wife. Examples of psychological abuse behaviors include: threatening, trying to isolate the partner from family and friends because he/she thinks that they do not approve of him/her, and intimidating. Examples of verbal abuse behaviors include: being sarcastic, nagging, name calling, criticizing, and swearing.

Pearson correlation were run within each ethnic group to discover any relationships between judgements of abusiveness and judgments of typicality of the behaviors. Analyses of variance were also performed to see if there were ethnic and/or gender differences on both the total typicality and abuse scale scores, and also on each of the sub scales. In addition, paired sample T-tests were run separately within each ethnic group to determine whether there were differences in judgments of abusiveness and typicality for husband-perpetrated versus wife-perpetrated physical, psychological and verbal abuse behaviors.

Results

Pearson correlations between judgments of abusiveness and judgments of typicality for husband perpetrated behaviors and for total abuse and typicality are shown in Table 3. In the Caucasians, none of the abuse scales were correlated significantly with the typicality scales.

In the Japanese sample, however, total abuse was significantly positively correlated with total typicality (r= 0.23, P<0.0001). in addition, judgments of the abusiveness of husband- perpetrated verbal abuse was significantly positively correlated (r=0.20, P<0.05) with judgments of the typicality of those behaviors.

For the Asian American sample, on the other hand, judgments of the abusiveness of husband-perpetrated psychological abuse (r= -0.24, P<0.05) were significantly negatively correlated with judgments of the typicality of the husband-perpetrated psychological abuse.

In the Singaporean sample, both total abuse and total typicality (r=0.29, P<0.005); in addition to judgments of abusiveness and judgments of typicality of husband perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors (r=0.24, P<0.05) were significantly positively correlated. All significant correlations were of small magnitude.

Table 4 shows the Pearson correlations for judgments of abusiveness and typicality for wife perpetrated abuse behaviors. The variables were not significantly correlated for the Caucasians, while some variables were significantly correlated in the Asian samples.

In the Japanese sample, judgements of abusiveness and judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors (r= -2.24, p<0.0001) were found to be significantly correlated in the negative direction. On the other hand, judgements of abusiveness and judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors (r=0.30, p<0.0001) were significantly correlated in the negative direction.

Judgements of abusiveness and judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors (r= -0.28, P<0.005) were found to be significantly correlated in the negative direction for the Asian American sample. On the other hand, judgements of abusiveness-typicality of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors (r= 0.21, p<0.05) were found to be significantly correlated in the positive direction in the Singaporean sample.

The analyses of variance as shown in Table 5 revealed that total abuse scores, judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors, and judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors differed significantly by gender. In particular, males were found to have significantly lower total abusive score than females did. In other words, males viewed the abuse behaviors as a whole to be less abusive than females. On the other hand, males had significantly higher scores on judgments of the abusiveness of both wife perpetrated psychological and wife-perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors. This meant that males viewed wife perpetrated psychological abuse and verbal abuse behaviors to be more abusive than females did (see appendix A).

Analyses of variance by ethnicity revealed significant differences in judgements of abusiveness and typicality. Mean scores on each of the dependent variables are shown in Table 6.

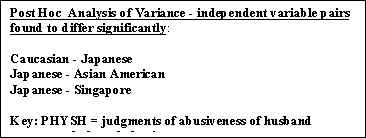

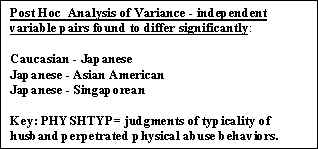

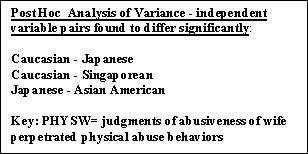

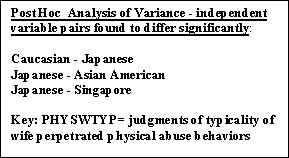

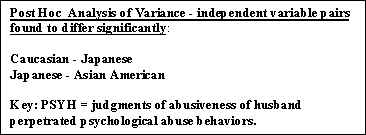

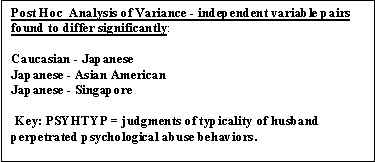

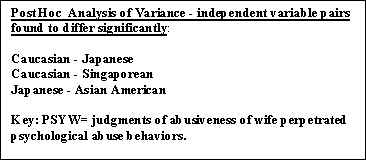

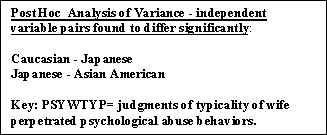

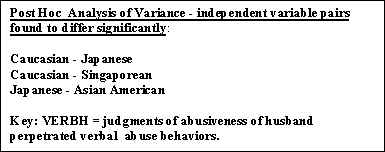

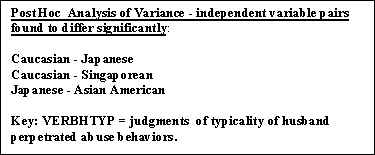

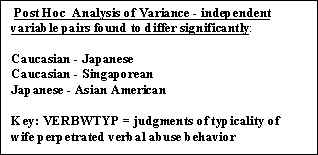

Post hoc tests (See Appendix B) revealed Caucasians had significantly

higher scores than the Japanese on all the variables investigated. In other words the

Caucasians viewed all forms of abusive behaviors as more abusive and more typical then the

Japanese did. Caucasians were also found to score significantly higher than Singaporeans

do on judgments of abusiveness of wife-perpetrated physical abuse and wife-perpetrated

verbal abuse. Thus, Caucasians viewed these behaviors as more abusive than the

Singaporeans did. In addition, Caucasians also scored significantly higher than the

Singaporeans did on judgments of typicality of both wife-perpetrated and

husband-perpetrated verbal abuse. Caucasians viewed these behaviors as more typical in

their culture than Singaporeans

did. Furthermore, Caucasians had significantly higher scores than the Asian Americans in

ju dgments of abusiveness of wife-perpetrated psychological abuse.

The Japanese had significantly lower scores than the Asian Americans on all variables except for judgements of abusiveness of wife-perpetrated psychological abusive behaviors. In addition, the Japanese also had significantly lower scores than the Singaporeans on judgments of abusiveness of husband-perpetrated physical abuse, husband perpetrated verbal abuse, wife-perpetrated verbal abuse and wife-perpetrated psychological abuse. In addition, the Japanese also scored significantly lower than the Singaporeans did on judgments of typicality of husband-perpetrated physical abuse, husband-perpetrated psychological abuse and wife-perpetrated physical abuse. Asian Americans were found to score significantly lower than Singaporeans do only in judgments of abusiveness of wife-perpetrated verbal abuse. In other words Asian Americans saw wife-perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors as less abusive than Singaporeans did.

Paired sample t-tests for each ethnic group is shown in Table 7. In the Caucasian sample, judgements of abusiveness of husband versus wife perpetrated physical (T(149)=-4.09, p<0.0001), psychological (T(149)=8.14, p<0.0001) and verbal (T(149)=12.69, p<0.0001) abuse items were significantly different in mean scores. In addition, mean scores on judgments of typicality of husband versus wife perpetrated physical (T(149)=4.87, P,0.0001) and psychological (T(149)=12.14, p<0.05) abuse behaviors were found to differ significantly. For the Caucasians, judgments of hypothetical female perpetrated abuse behaviors were seen as more abusive compared with hypothetical male perpetrated abuse behavior only for physical abuse. The other variables were all seen as more abusive or typical when perpetrated by a hypothetical male compared to a hypothetical female.

In the Japanese sample, all mean scores of judgements of abusiveness of husband versus wife perpetrated physical (T(173)=-1.92, p<0.0001), psychological (T(175)=10.43, p<0.0001) and verbal (T(175)=2.94, p<0.005) abuse were also found to differ significantly; while only mean scores in judgments for typicality of husband versus wife perpetrated physical (T(174)=7.31, p<0.0001) and psychological (T(175)=-6.17, p<0.0001) abuse behaviors were found to differ significantly. For all variable pairs that were found to differ significantly, the direction of the difference were the same in our Japanese sample as for the Caucasians.

On the other hand, only judgments of abusiveness of husband versus wife perpetrated physical (T(106)=7.45, p<0.0001) and psychological (T(106)=6.96, p<0.0001) abuse behaviors differed significantly for the Asian Americans. Furthermore, as with the Japanese sample, only mean scores in judgments for typicality of husband versus wife perpetrated physical (T(106)=4.36, p<0.0001) and psychological (T(106)=8.06, p<0.01) abuse behaviors were found to differ significantly. For all variable pairs that were found to differ significantly, the direction of the difference were also the same for the Asian Americans,

For the Singaporean sample, mean scores of judgements of abusiveness of husband versus wife perpetrated psychological (T(101)=2.26, p<0.05) and verbal (T(101)=3.69, p<0.0001) abuse behaviors were found to differ significantly; while all mean scores for judgments of typicality of husband versus wife perpetrated physical (T(99)=4.08, p<0.0001), psychological (T(102)=-2.76, p<0.01) and verbal (T(102)= -3.10, p<0.005) abuse behaviors were found to differ significantly. In the Singaporean sample two of the significant variables (psychological and verbal abuse behaviors) were viewed as more typical for a hypothetical female perpetrator as compared to a male perpetrator. In other words, Singaporeans viewed psychological and verbal abuse behaviors as more typical when the hypothetical perpetrator was female.

Discussion

In the present study, few gender differences were observed. Scores on only three variables differed significantly by gender--namely, total abuse score, and judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated psychological and verbal abuse. Females had significantly higher scores on the total score than males did. This means that overall females viewed the behaviors being investigated as more abusive in general than males did. On the other hand, males viewed psychological and verbal abuse that is perpetrated by a hypothetical wife as significantly more abusive than females did. The findings here are consistent with results found by Lim (1998), who, using a 28-item modified Malley-Morrison et al (1994) typicality scale with three ethnic groups ( Caucasian, Asian American and Singaporean ), found significant gender differences only in female perpetrated psychological abuse. Males were found to view wife perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors as more abusive than females did. It is interesting that the male respondents saw hypothetical female (wife) perpetrated psychological behaviors as more abusive. This seems to point to the general tolerance of male perpetrated abuse as only the abuse behaviors that were more commonly used by females were judged by males to be more abusive. On the other hand, females did not judge abuse behavior more commonly used by males to be more abusive than males.

The results of the analyses of variance support the position that judgments of the typicality and abusiveness of physically, psychologically, and verbally abusive behaviors vary cross-culturally. In particular, Caucasians appear to view abusive behaviors as more typical and abusive than the Japanese. We believe that these differences may be explainable at least in part as a consequence of different experiences of romantic love and emotional intimacy. For example, romantic love is likely to be more important basis for marriage in American (individualistic) society than in Japanese (collectivistic) society (Dion and Dion, 1990). Moreover, Dion and Dion (1990) stated that "psychological intimacy in a marital relationship is more important or marital satisfaction and personal well-being in American (individualistic) society than for those in Japanese (collectivistic) society" (p.320).

In an individualistic culture, where individuals place great importance on emotional intimacy, problems in intimacy may be more associated with abusive behaviors (Dion & Dion, 1990.) Similarly, Straus and his colleagues (1981) have discussed linking of love and violence in North American families; the assertion that " I only hit you because I love you" may transfer beyond the family of origin and lead North Americans to view abusive behaviors by their intimate partners as more typical than in cultures that link discipline to other goals besides expressing love.

On the other hand, Japanese (collectivistic) society has traditionally placed less emphasis on the importance of psychological intimacy in marriage. Marriages were generally arranged based on the two families' similarity in rank, occupation, and/ or status (Fukuda, 1991). In this tradition, the wife's role is more passive or tolerant of her husband because it is important to maintain good family relations. Moreover, Japanese society puts emphasis on the custom of saving face and places high value on avoiding a loss of public esteem. Consequently, people tend to keep potentially scandalous behavior confidential rather than make it public. In this context, it is reasonable for Japanese respondents to characterize abusive behaviors as less abusive and or less typical then respondents from more individualistic societies.

The difference in judgments of the typicality and abusiveness of intimate relationship may also stem in part from the different educational levels reported by the different samples. For example, only 39.2% of the Japanese respondents reported at least some college education as compared with 89.3% of American respondents. Many Japanese students in our sample went to trade schools or technical schools such as hair dressing schools. These Japanese participants may not have been exposed to the same education that the Americans had regarding judgments of verbal and physical aggression as abuse. Similarly individuals from different cultures may be exposed to different attitudes towards abusive behaviors in their public media, influencing their judgments. For example, the image of violence in the United States are largely portrayed through physical violence. In our experience, most of the media campaigns on violence have focused on physical violence. On the other hand, Singapore approaches violence in a more preventive strategy whereby the "Courtesy Campaign" was promoted. People were encouraged to be polite to others, think of others and also to smile more. This campaign has served to sensitize the people of Singapore to verbal cues and may have affected their judgments to bias on verbal and psychological abuse.

Paired sample t-tests revealed gender-of-perpetrator differences in all four ethnic groups regarding attitudes towards intimate violence. As shown in Table 7, in general, abusive behaviors were judged more typical or abusive when the hypothetical perpetrator was male. The gender-of-perpetrator differences in attitudes were largely in the same direction for all four ethnic groups. Two interesting findings were observed with this sample. Firstly, judgments on typicality of psychological abuse behaviors were judged more typical when the perpetrator was female only in the Singaporean sample, unlike in the other ethnic groups whereby psychological abuse behaviors were viewed as more typical when perpetrated by males. Secondly, only the Singaporean subjects had response (gender) bias for judgments of verbal abuse. As mentioned above, the Singapore participants saw verbal abuse behaviors more typical when perpetrated by a hypothetical female. This may have been partly due to the influence of the "Courtesy campaign" as discussed above. There seems to be some cultural influences in even the response bias of participants but on the whole, there are greater between group differences than within group and gender differences in attitudes towards intimate violence.

One limitation of this present study include the

possibility that our results are not actual cultural differences in judgments concerning

abusive behaviors but due to culturally-based response bias or a culturally biased

questionnaire. Abusive behaviors may be just as typical and/ judged just as abusive in

more collectivistic cultures. Their response may be the result of not wanting to

"own-up" to values that seem discrepant with their cultural emphasis on group

harmony. Another limitation of our study involves the generalizability of our findings.

The participants in our study were mainly college students or in some cases from highly

select populations of the societies. Therefore, the findings here may not reflect the

societies on the whole until results using other segments of the communities can be

assessed. Future research should focus on instrument development to ensure that the

instrument is applicable cross culturally. Participants that are involved in intimate

relations from the above ethnic groups should be asked regarding their attitudes towards a

real scenario to investigate any discrepancies in attitudes that may be due to the nature

of the questions asked. In addition, possible differences in judgements of intimate

violence should be analyzed using ethnic by gender analyses to give a clearer picture on

attitudes towards intimate violence.

References

Bethke, T. M., & DeJoy, D. M. (1993). An Experimental study of Factors Influencing the

Acceptability of Dating Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8, (1),36-51.

Bookwala, J., Frieze, I. H., Smith, C., & Ryan, K. (1992). Predictors of Dating

Violence: A Multivariate Analysis. Violence and Victims, 7, (4), 297-311.

Briere, J. (1987). Predicting Self-Reported Likelihood of Battering: Attitudes and

Childhood Experiences. Journal of Research in Personality, 21, 61-69.

Derezotes, D. S., & Snowden, L. R. (1990). Cultural Factors in the Intervention of

Child Maltreatment. Child and Adolescent Social Work, 7, (2), 161-175.

Dion, K. K., & Dion, K. L. (1993). Individualistic and Collectivistic Perspectives on

Gender and the Cultural Context of Love and Intimacy. Journal of Social Issues, 49,

(3), 53-69.

Fukuda, N. (1991). Women in Japan. In L. L. Adler (Ed), Women in cross-cultural perspective (pp.205-219). Westport, CT:Praeger.

Gray, E., & Cosgrove, J. (1985). Ethinocentric Perception of Childrearing Practices in

Protective Services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 9, 389-396.

Ho, C. (1990). An Analysis of Domestic Violence in Asian American Communities: A Multicultural Approach to Counseling. In L.S. Brown & M.P.P.Root. (Eds.), Diversity and Complexity in Feminist Therapy (pp.129-149). New York; Harrington Park Press.

LaFromboise, T., Coleman, H. L. K., and Gerton, J. (1993). Psychological

Impact of Biculturalism: Evidence and Theory. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3).

Lim, L. (1998) Gender and cultural differences in judgments of typicality-abusiveness

of couple behaviors. Poster presented at the 1998 American Psychological Society

Conference in Washington, DC.

Makepeace, J. M. (1986) Gender differences in courtship violence victimization. Family Relations, 35, 383-388.

Marshall, L. L. (1994). Physcial and Psychological Abuse. In W. R. Cupach & B. H. Spitzberg (Eds.), The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication (pp.281-311). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Miller, S. L., & Simpson, S. S. (1991) Courtship Violence and social control: does gender matter? Law and Society Review, 25(2), 335-365.

Park, R. E. (1928). Human migration and the marginal man. American Journal of Sociology,

5, 881-893.

Stonequist, E. V. (1935). The problem of marginal mind. American Journal of Sociology,

7, 1-12.

Straus, M. A., Gelles, R. J., and Steinmetz, S. K. (1981) Behind closed doors : violence in the American family. Garden City, N.Y: Anchor Books.

Sugarman, D. B., & Hotaling, G. T. (1989). Dating violence: Prevalence, context,

and risk markers. In Pirog-Good, M. A., and Stets, J. E. (Eds.), Violence in Dating

Relationships. Praeger, New York.

Triandis, H. C. (1990). Cross-cultural studies of individualism and collectivism.

In J. J. Berman (Ed.), Cross-cultural perspectives: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation,

1989. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

| Caucasian | Japanese | Asian American | Singaporean | |

| Mean age | ||||

| At least some college education | ||||

| Female | ||||

| No current relationship | NA | |||

| Marital status-single |

*= includes junior college and some four year college.

Table 2: Example of Malley-Morrison et. al (1994) Typicality Scale.

__________________________________________________________________

Typicality Scale

For each of the following scenarios, indicate on seven-point scales first how typical you think such an occurrence is in your culture (ranging from 0 meaning not at all typical to 6 meaning extremely typical), and then how abusive you think it is (ranging from 0 meaning not at all typical to 6 meaning extremely typical).

How typical? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

How abusive? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

How typical? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

How abusive? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

__________________________________________________________________

Table 3: Pearson Correlations between judgements of abusiveness and judgements of typicality for husband perpetrated physical abuse, psychological abuse and verbal abuse for Caucasians, Japanese, Asian Americans, and Singaporeans.

Caucasian |

Japanese |

Asian American |

Singaporean |

|

| Total abuse score - Total typicality score | .10 | .234**** | .11 | .29*** |

| Judgments of abusiveness of husband perpetrated physical abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of husband perpetrated physical abuse behaviors | .10 | -.03 | -.12 | -.01 |

| Judgments of abusiveness of husband perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of husband perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors | .06 | -.03 | -.24* | .24* |

| Judgments of abusiveness of husband perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of husband perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors | .08 | .20** | .01 | .16 |

*P<.05, ** P<.01, *** p<.005, **** p<.001

Table 4: Pearson Correlations between judgements of abusiveness and judgements of typicality for wife perpetrated physical abuse, psychological abuse and verbal abuse for Caucasians, Japanese, Asian Americans, and Singaporeans.

Caucasian |

Japanese |

Asian American |

Singaporean |

|

| Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors | .09 | -2.24**** | -.28*** | .05 |

| Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors | -.02 | -.04 | -.03 | .21* |

| Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors | -.05 | .30**** | .08 | .15 |

*P<.05, ** P<.01, *** p<.005, **** p<.001

Table 5: Analyses of variance for Gender and Ethnicity

| Gender | Ethnicity | |

| Total abuse score | F(521,3)=5.58* | F(521,3)=23.81**** |

| Total typicality score | F(521,3)=.55 | F(521,3)=8.58**** |

| Judgments of abusiveness of husband perpetrated physical abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=.38 | F(521,3)=9.38**** |

| Judgments of typicality of husband perpetrated physical abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=.001 | F(521,3)=6.02**** |

| Judgments of abusiveness of husband perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=2.22 | F(521,3)=10.37**** |

| Judgments of typicality of husband perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=.007 | F(521,3)=9.97**** |

| Judgments of abusiveness of husband perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=2.27 | F(521,3)=21.96**** |

| Judgments of typicality of husband perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=.28 | F(521,3)=4.41*** |

| Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=2.23 | F(521,3)=9.70**** |

| Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=.91 | F(521,3)=6.67**** |

| Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=16.55**** | F(521,3)=11.02**** |

| Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=.23 | F(521,3)=7.12**** |

| Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors | F( 521,1)=4.46* | F(521,3)=19.37**** |

| Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors | F(521,1)=1.16 | F(521,3)=6.40**** |

*P<.05, ** P<.01, *** p<.005, **** p<.001

Table 7: Paired sample t-tests for Caucasian, Asian American, Japanese and Singaporean.

Caucasian |

Japanese |

Asian American |

Singaporean |

|

| Judgments of abusiveness of

husband perpetrated physical abuse behaviors - Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors |

T(149)= -4.09**** |

T(173)=-1.92**** |

T(106)=-.62 |

T(99)=.304 |

| Judgments of abusiveness of

husband perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors - Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors |

T(149)=8.14**** |

T(175)=10.43**** |

T(106)=7.45**** |

T(101)=2.26* |

| Judgments of abusiveness of

husband perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors - Judgments of abusiveness of wife perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors |

T(149)=12.69**** |

T(175)=2.94*** |

T(106)=6.96**** |

T(101)=3.69**** |

| Judgments of typicality of

husband perpetrated physical abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated physical abuse behaviors |

T(149)=4.87**** |

T(174)=7.31**** |

T(106)=4.36**** |

T(99)=4.08**** |

| Judgments of typicality of

husband perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated psychological abuse behaviors |

T(149)=12.14* |

T(175)=-6.17**** |

T(106)=8.06** |

T(102)=-2.76** |

| Judgments of typicality of husband perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors - Judgments of typicality of wife perpetrated verbal abuse behaviors | T(149)=-.61 |

T(175)=-1.57 |

T(106)=054 |

T(102)= -3.10*** |

*P<.05, ** P<.01, *** p<.005, **** p<.001

Appendix A: Mean scores on variables that differ significantly by Gender.

Appendix B: Mean scores for judgments found to differ significantly by ethnicity.

Note: 2.00= Japanese