Figure 1

Csaba Horgász

(1995)

The objective of this paper is to illustrate by

means of psychoanalysis some aspects of the creative process of composing

music. In my opinion, the internalized object relations - which are represented

in the personality in the form of unconscious fantasies - play a decisive

role in the formulation of artistic concept of the world (cf. Horgász

1993).

I will illustrate this

hypothesis by analyzing the psychological motives underlying Bartók's

early compositions, in first Violin Concerto (op. posthum.) and Two Portraits

(op. 5). I intend to show a few of Bartók's characteristic object

relation attitudes (cf. Horgász 1995) and

to illustrate their musical representation.

Hitherto

little known documents, the collection of Bartók's letters to violinist

Stefi Geyer between 1907-1908 and published by the Swiss conductor Paul

Sacher1 in Basel in 1979, help reveal Bartók's typical

object relation attitude. The collection contains twenty letters, six postcards,

and diary-like notes. In none of his later writings do we find such sincere

and profound confessions as in these passionate communications written

at age twenty-seven. This was the only brief period in the composer's life

when he allowed, in his music as well as his letters, an insight into his

hermetically sealed internal world.

The

close relationship between Bartók and Stefi Geyer lasted only a

little more than seven months. In the beginning, their meetings took the

form of playing music together, but later, due to Stefi Geyer's tours abroad

and Bartók's folk-song collecting trips,2

their relationship became confined to correspondence. These documents enable

us to follow closely the development of the relationship.

Bartók

soon fell in love with the girl who returned his feelings initially, but

soon they discovered that they disagreed on fundamental issues. For instance,

the question of marriage was such a sensitive issue. Bartók's unusual

views about marriage may well have disquieted her love for him: "As

regards tradition, it's but holy gospel for average people. And the Stefi

Geyers are born to eschew its yoke... I think that everyone, man and woman,

if it is in one's power, must fight against the bonds of tradition. This

fight is actually but a striving for autonomy, to be independent of everyone

or of everything, as well as to be in control of ourselves..." (July

27, 1907, my italics - Cs.H.)

Bartók

was wary of dependence in other respects also. About friendship, he wrote:

"In

my mind I have already come to the conclusion that I will not have any

male friends, because I cannot. Only an autonomous person would, which

fact virtually precludes harmony in outlook." (August 20, 1907)

It

seems, he was afraid that acceptance of a partner's views would be tantamount

to surrendering his own autonomy, thus a danger to his own independence.

His

letters written at the age of eighteen or nineteen to his mother reveal

that his distrust and anxieties concerning a dependent position in a relationship

were originally directed at his primary object relation, his mother: "...

it is not good and it is unnecessary for a mother to be completely enslaved

to her child. Freedom!" (Bartók, Jr. 1981a,

130)

Márta

Ziegler, Bartók's first wife, recalled (Bónis

1992), that his mother was a highly dependent individual3

who devoted her entire life to her son. Bartók's letters as a young

man to his mother show, however, that for him this devotion was more of

a burden than a source of joy. He wrote, for instance: "Please, don't

be so concerned with me, because it's very unhealthy if someone pays too

much attention to another, whoever that may be..." (Bartók,

Jr. 1981a, 38)

Bartók

not only wanted to avoid situations demanding compliance and involving

dependence, it was also important to him to have others close to him accept

his views, in other words, to bring them under his control. He admits to

this with astonishing openness in the following letter to Geyer: "It

is wholly impossible to improve people, or, more appropriately, to train

them to behave in ways other than what their nature predestined them for.

So much agony sprang from my endeavor to do just that. I would have liked

many things to be very different in those close to me. Clearly, this desire

was motivated by disguised selfishness. It makes communication so much

more agreeable if I can shape a person to my liking... This is all over

now, and my independence in this respect is secured for ever." (July

27, 1907)

This

desire to transform others did not vanish, regardless of what Bartók

believed. His letters to Geyer, in the beginning anyway, show that he did

his best to make her accept his views. He even used projective identification,

the method of applying emotional pressure to accomplish this.

The

question of religion was a cardinal issue of conflict between them. Bartók

was unable to forgive Geyer her belief in Catholic doctrine and even less

the fact that the girl he was in love with was committed to somebody with

which he could not compete: "...if I ever crossed myself, it would signify

'In the name of Nature, Art and Science...' Isn't that enough?! Must you

have the promised 'hereafter' as well? That's something I can't understand."

(September 6, 1907, cf. Bartók 1971, 82)

It's

very likely that the real issue in their relationship concerned not so

much the substance of marriage and religion, but the object relation pattern

that Bartók wanted to create in the course of and through their

argument. Bartók tried to escape from his dependent relation to

her (because his in love) by assuming a position of dominance in a way

that he be in an asymmetrical controlling relation to her: "Will you

allow me to supply you with reading matter from time to time?... You needn't

be afraid that reading will blight your youth; even if it were to shorten

it, you would be amply compensated by all the pleasure you would get from

it", he wrote in his above cited letter (September 6, 1907, cf. Bartók

1971, 83).

Geyer,

however, began to assume a defensive position, rejecting Bartók's

dominating attitude, and became alienated from her admirer. Her resistance

and alienation brought on a change in Bartók's self-confident attitude

and their relationship came to a turning point. As Bónis writes:

"Instead

of winning her, Bartók's arguments intimidated the traditionally

reared girl; her rejection of them - and the total rejection of the man

- was inevitable and immediate. From that time on a peculiar alternation

between hope and despair characterized Bartók's letters. They became

increasingly personal and passionate - focussing increasingly on the violin

concerto he was working on." (Bónis 1992,

36.)

Bartók's

next letter is an important document on artistic creativity and, therefore,

worth closer examination.

As

we have seen, Bartók was compelled to face the fact that his efforts

to change and to control Geyer were ineffective: "Why are you such a

very weak person, and why are you afraid of reading and learning?! This

is what drives me to despair... Would you still refuse to accept books

from me even if I only gave you books in which there is merely a total

lack of reference to god - or at least only pious reference?!" (September

11, 1907, cf. Bartók 1971, 86.)

In

the end, he was totally overcome by the feeling of hopelessness and despair

and in this state of despondency he even considered suicide.4

However, he was quick to repress the embarrassing realization of his failure:

"I

would never attempt to talk you out of your faith, distressed though I

am by your present state of mind. Move the first moment of crisis, you

would relapse, I am sure--- Yes, let us drop the subject; we may discuss

it again - at some later date, maybe, but not now." (Ibid., my italics

- Cs.H.)

Repression,

however, was only partial; Bartók's defeat on this subject, in the

religious dispute, left its mark on his mood. It dawned on him that he

may lose the girl, if he had not lost her already: "After reading your

letter, I sat down to the piano - I have a sad misgiving that I shall never

find any consolation in life save in music. And yet---" (Ibid., 87.)

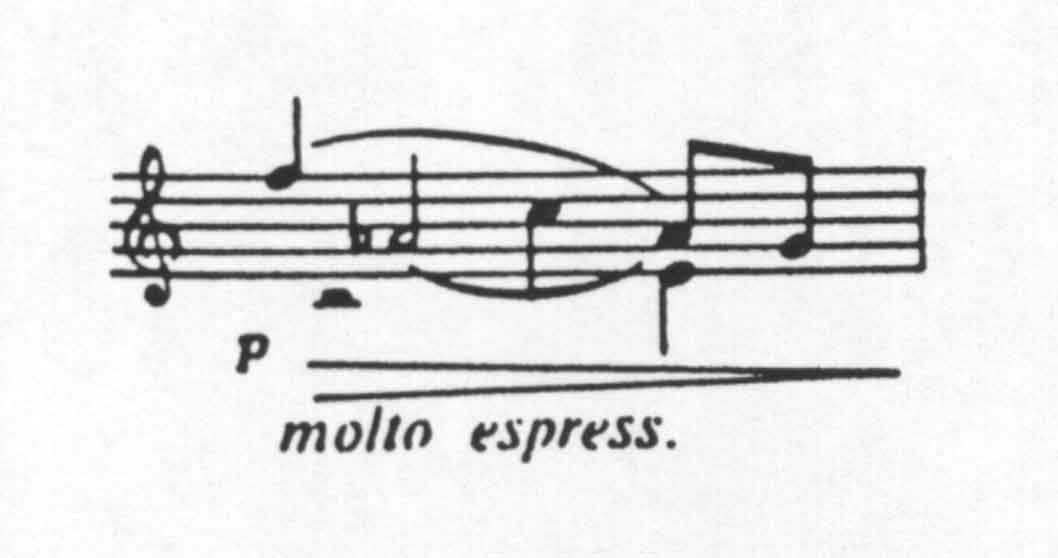

Figure 1

"The unfinished sentence is followed by nine

bars of music: a sort of funeral march, the prototype of the piano piece

- the 13th Bagatelle - called Elle est morte [she is dead]. Above the fourth

chord in C sharp minor Bartók wrote: 'This is your Leitmotiv'",

wrote Bónis (1992, 36).

These

few lines reveal the musical creative process as it evolves through the

inner psychic dynamics of the personality. We are witness to the phenomenon,

described by a number of psychoanalyst authors, when object loss activates

the creative process.

Let

us review the events in psychoanalytical terms. First and foremost, we

are witness to an object relation conflict: By applying the method of projective

identification, Bartók tried to establish a special, controlling,

narcissistic object relation pattern with Geyer, which she resisted. Bartók's

frustration by the rejection gave rise to aggressive feelings towards her.

This was first manifested in his attack on her religious convictions, then

he turned against himself as his suicidal fantasies reveal.

When

the ideal external object became unattainable, Bartók - in Freud's

terminology - was forced to withdraw his libido and sublimate it in music:

"I have a sad misgiving that I shall never find any consolation in life

save in music," he wrote, reinforcing Freud's theory that a work of art

is "but" a fantasized wish fulfillment.5

The

musical sentence in the letter tells us what wish was being fulfilled:

"this is your Leitmotiv," he wrote above one of the motives which points

to her presence in his music (phantasy). The desired object relation, which

became impossible in real life, became realized in fantasy and thereby

in the creative act and its final product, music.

László

Böhm's Dictionary of Music defines leitmotif (Leitmotiv; leading motive)

"as a musical motive used to denote a dramatic situation or a person constantly

recurring in the composition as a characteristic feature" (Böhm

1990, 149). Psychologically speaking, Bartók's leitmotif is

the musical representation of an internal object, the ideal of Stefi Geyer.

The

leitmotif in the letter corresponds with the main theme of the 1st movement

of the Violin Concerto he finished six months later.6

(In this context, we may also interpret the writing of the Violin Concerto

as a continuation of mourning work.) Bartók used this 1st movement,

as I will show below, in his composition, Two Portraits, and called it

the Ideal Portrait. In other words, the leitmotif in the letter is but

a musical visiting card presenting the ideal Stefi Geyer. The attribute,

Ideal, suggests that the portrayal of Stefi Geyer as an accepting, acquiescent

person who returns his affections, who is free of the negative features

separating them. This idealization and, thus, wish-fulfilment is made possible

by discarding the negative aspects.

However,

in the letter, the leitmotif is embedded in a kind of funeral march which

qualifies his relation to the ideal object as depressive. The creative

process could not ease the negative affects. These are expressed in the

accompaniment. On the whole, the musical idea noted in the letter depicts

Bartók's ambivalence toward the object: the leitmotif represents

the idealized object, the accompaniment the controversial depressive affects

which are directed at her and are related to object loss and the death

of the internal object. The psychological meaning of the composition may

by summarized as follows: Bartók carried the picture of a desired,

loved object in his internal world, which, due to the aggression arising

from ambivalence, became an damaged, dead object.

This, however, did not mean the end of the relationship

by far. The conflict did not weaken Bartók's attraction; his belief

in the future of the relationship rekindled time and again. The geographical

distance that their travels involved contributed to the maintenance of

this idealization (which in this case belongs to the sphere of manic defense),

though Bartók did sense its falseness. His internal world came to

life again and he wrote the following in his next letter in which he used

three variants of the Stefi Geyer leitmotif to address her: "Your Leitmotivs

flutter around me, I live with and in them all day long as if I were dreaming

under narcosis. And it is as it should be; this is the kind of opiate I

need for my work, even if it is nerve-racking, poisonous, and dangerous."

(September 20, 1907)

Obviously,

for Bartók the leitmotifs were internal objects representations;

and the creative process itself was a composition of object relations of

his fantasy. The quotation is a fine illustration of the way Bartók

built an internal object world in his intrapsychic world, in his music,

which kept him spellbound.

These

fluttering leitmotifs gave birth to the 1st Violin Concerto, the plans

for which engaged Bartók's attention almost from the moment he met

Geyer. The concerto comprises two antipodal movements. As already mentioned,

the 1st movement is a portrait of the ideal Stefi Geyer. In his letter

of November 26, 1907, Bartók wrote as follows:

Figure 2

"this idealized musical picture contains every

thought and feeling I had at the time. I never wrote spontaneous music

such as this..." (November 26, 1907)

In

another letter to Geyer, Bartók introduces the main motive of the

2nd movement as follows: "Wasn't that 14-year-old elfish little girl,

whom I met in Jászberény, Stefi Geyer?!! Oh dear! Hurry,

please, and readjust your photograph or, else, depictions like this will

appear throughout the composition!" (August 20, 1907)

Figure 3

(Bartók's handwriting)

I have not seen the photograph that evoked

Bartók's disapproval, but he added a caption in English to the score,

"G. St. when she is smoking a pipe." She was fourteen when Bartók

first met her. At the time of the dramatic turn in their relationship,

she was nineteen; it may well be that the photograph showed her as an adult

perhaps sporting a pipe, which disrupted the ideal picture Bartók

had of her.

Thus,

the ideal 1st movement of the Violin Concerto is supplemented with an ironic,

elfish 2nd movement. Its tempo designation is allegro giocoso, that is,

playful, comic, rapid. In this 2nd movement, the ideal Stefi Geyer becomes

the victim of a fantasy game, of a slight distortion, revealing Bartók's

ambivalent feelings concerning her. The caption above the third theme of

the movement also reflects this ambivalence: thickly, growling (cf. Kroó

1974).

The

main theme itself was the result of the transformation - inversion and

break through - of the leitmotif (Bónis 1992,

40):

Figure 4

Under the influence of his ambivalent emotions, the composer performed a transformation, a cognitive operation on the internal object represented in the potential space (Winnicott 1971) of music.

As the conflict between Bartók and Geyer

sharpened - to which, according to the letters, her ambivalent, beguiling

behavior also contributed - Bartók's feelings toward her became

increasingly immoderate. This can be easily traced in the change in Bartók's

creative concept. At first, he planned the Violin Concerto to consist of

three movements and described his dramaturgic plan as follows: "Already

I have drawn a musical picture of the idealized St. G. - it's heavenly,

intimate; I also have another of the fiery St. G. - it's humorous, clever,

amusing. Now, I should compose a picture of the indifferent, cool, silent

St. G. But this would be hateful music." (November 29, 1907)

The

unequivocal polarization of his feelings for Geyer is clear in the letter

dated ten days later: "You are a dear, a good, a fairy-like, an enchanting

girl! who has only to draw a few lines to chase the dark, grimly swirling

clouds from the sky and make the bright sun shine on me. - You are a taciturn,

a bad, a cruel, a miserly girl! to begrudge me your powers of enchantment!"

(December 8, 1907)

A

few lines down he wrote the same in terms of music: "One cannot always

be a 6/8 D F sharp A C sharp - D [leitmotif], sometimes

Figure 5

one must also be." (Ibid.)

In the end, almost two weeks

later, he decided to use the two movement form: "One day this week the

seemingly indisputable necessity suddenly occurred to me, as if it were

inspired, that your composition can have but 2 movements. Two contrasting

portraits: that's all. I can only wonder now that I did not see the truth

of this before." (December 21, 1907)

Although

the two movements of the Violin Concerto impersonate two different aspects

of Geyer (the ideal and the elfish), thereby expressing the dual form design

so characteristic of Bartók, the 2nd movement is merely a mild poke

at the ideal Stefi Geyer, which failed to adequately convey Bartók's

growing irritation and anger. His efforts to ward off her negative aspects

and those of the relationship were in vain, proving more resilient. For

this reason he was thinking of writing a third movement which would have

been hateful music.

This

hateful music did not have to wait long. In May 1908, Bartók finished

the Fourteen Bagatelles (op. 6) for pianoforte. The last of these is a

fast waltz based on the Stefi Geyer leitmotif and is called Ma mie qui

danse (My love dances) (cf. Kroó 1974). According

to Geyer's comment, the piano piece is a reaction to our separation (cited

by Tallián 1981, 79). Subsequently, Bartók

orchestrated this originally pianoforte piece and fitted it into the first

movement of the Violin Concerto, leaving out the original second movement.

Thus was the Two Portraits for Orchestra (op. 5) composed (around 1914).

Bartók called the first movement of the new composition One Ideal

and the second One Grotesque. According to György Kroó, "We

do not know whether the piano piece composed as the fourteenth of the Bagatelles,

which was the basis of the 'Grotesque' portrait, was in fact originally

conceived as the third movement for the Violin Concerto. Was this the 'hateful'

music that Bartók was not capable of composing in February 1908?

He produced it later that same spring and it is possible that this too

was a confession of love, as the inscription of the sketch '...con amore'

would seem to indicate" (Kroó 1974, 41).

In

other words, after the breakup Bartók replaced the second, amusing,

movement of the Violin Concerto with hateful music. This music conveyed

more faithfully the intense, destructive anger he felt toward Geyer. With

the end of the relationship his repressed emotions, expressed as playful

irony in the 2nd movement, were released without restraint in the Grotesque

Portrait.

In

the unified composition of the Two Portraits the split in emotions form

an integral whole and the splitting becomes ambivalence.7

Let

us compare the main themes of the Two Portrait's Ideal and Grotesque movements

and note their sameness and variances:

Figure 6

(By Ernõ Lendvai 1971, 66.)

The main theme of both movements is constructed

from the same musical material, namely, Geyer's leitmotif. As we have shown,

the leitmotif is the musical representation of an internal object. In this

case, we have two different expressions, or aspects, of the leitmotif,

or the internal object.

Preservation

of the schema, the perceptual Gestalt of the melodic passage ensures the

identicalness of the two thematic schemes. This stable cognitive structure,

musical skeleton (the rules of which may be studied by cognitive psychology

and musical theory jointly) carry or contain representation of the internal

object. Or, to put it simply: in the potential space (Winnicott

1971) of music, the internal object representation takes place in the

cognitive

structure.8

What

are the means by way of which musical representation of the different emotions

concerning the object, the different aspects of the object, that is, the

affective object relation is realized? The answer to this question lies

in the musicological elucidation of the principles of variation formation.

Here, I would like to only point out a few of the differences in the principles

of composition in the musical examples that Bartók used to convey

his conflicting feelings toward Geyer.

The

Ideal movement is a slow, intent composition in piano, with its meaning

interpreted by an intimate violin solo using a strict fugue structure.

The Grotesque movement, on the other hand, is a fast waltz, in which emotions

find release in a rapid succession of thunderous fortissimo bursts of various

effects; the intense emotions sweep away the sound of the solo instrument

by activating the entire orchestra (cf. Lendvai 1971).

Ernõ Lendvai summarizes the plot of the two movements as follows:

"I

would compare the 1st piece to a transfigured and deep sleep; but in the

case of the exposition, the dream expresses a yearning, unquenchable thirst,

the reprise [return], however, is the dream fulfilled... The ethereal Ideal

theme is made into a trivial and showy waltz, turning the sensitive features

of the 1st movement into a frantic spin. The basis of the dramatic concept

[of the 2nd movement] is that the Gotesque theme must die--with the reprise...

The reprise brings back the main theme not as a melody, but in the form

of inarticulate rattles, naturalistic imitation of sounds only to have

them burst like petards a few bars later...: the expanding funnel motive

explodes in the leading motive [leitmotif] D-F sharp-A-C sharp... The cadences

harmonically destroy the leading motive, D-F sharp-A-C sharp..." (Lendvai

1971, 62-74).

In

the Grotesque Portrait, Bartók took revenge on the frustrating bad

object who deserted him by the musical ridiculing, bursting, and, eventually,

the harmonic destruction of the leitmotif representing the object.

By

way of comparison, let us quote from one of his last letters to Geyer,

in which, giving vent to his agitation, he thought of destroying the Violin

Concerto which for him represented her and their relationship: "I finished

the score of the violin concerto on the 5th of February, the very day you

were writing my death sentence... I locked it in my desk, I don't

know whether to destroy it or to keep it locked away until it is found

after I die and the whole pile of papers, my declaration of love, your

concerto, my best work are thrown out." (February 8, 1908)

The

unbridled release of destructive impulses toward the object resulted in

the death of the internal object. Bartók was greatly worn out by

the breakup and, as a result of his serious sense of loss, he again became

obsessed with thoughts of self-destruction: "I've reached the ultimate

limit beyond which I cannot ask for anyone's love, cannot ask anyone to

share her life with me. I feel and I'm also convinced that nothing but

long years of solitude await me. I must give up completely this internal

happiness... Perhaps I may have the welcome opportunity to catch pneumonia

or some such thing, so that I may depart without attracting attention,

as I have nothing to expect." (February 8, 1908)

It

was in this mood Bartók composed the 13th Bagatelle mentioned above

when I introduced the first occurrence of the depressive spirited leitmotif,

called Elle est morte... (she died). This piece is also based on

the Stefi Geyer leitmotif and Bartók wrote above the last occurrence

of the motive in Hungarian: meghalt... (she died).

Figure 7

This variation of the leitmotif is a representation

of the dead internal object for whom Bartók erected a monument on

a score.

The

most important composition Bartók wrote immediately after the breakup

is his first truly mature and accomplished masterpiece, the String Quartet

No. I. It is closely related, spiritually and thematically, to the Violin

Concerto; in the first movement, Bartók grieves, as it were, for

his destroyed, dead internal object. Kroó wrote the following in

praise of the composition:

"That

dreamy tone of happiness, that havening, ethereal quality which permeated

the 'Ideal' portrait, gave way, as the dream itself faded from Bartók's

mind, to grievous lamenting and deep, hopeless sadness in the Lento movement

of the String Quartet No. 1. The playful scherzo in the second movement

of the Violin Concerto and the ironic scherzo of the 'Grotesque' had supplemented

and questioned the confession of the first movement; but in the String

Quartet No. 1 the slow movement now mourns for this same love." (Kroó

1974, 45)

Here,

I shall discuss only that part of the composition which shows a new variation

of the leitmotif representing - similarly to the 13th Bagatelle - the dead

internal object. Bónis comments on the composition as follows:

"The

introduction of the Quartet is built of the musical material of the concerto

[Violin Concerto]. The graceful main theme of the second movement of the

Concerto bearing the instruction, Allegro giocoso, introduces the Lento

movement of the 'String Quartet' as if in slow motion, like a lament. 'This

is my death song,' Stefi Geyer recalled Bartók to have written her

about this 'String Quartet' movement..." (Bónis

1992, 42-43)9:

Figure 8

This completes the musical representation of the

intrapsychic dynamics that characterized the course of Bartók's

relationship with Stefi Geyer.

It

exceeds the limits of the present paper to trace how Bartók found

his way back to life from the "realm of emotional death" in the String

Quartet No. I, symbolized by the clear, ancient pentatonic melody of the

"Székely dirge" (Bónis 1992).

I

trust, however, that in the foregoing I have accomplished my objective

to illustrate the phenomenon of musical object representation.

In

conclusion, allow me to make a few theoretical observations.

Winnicott

relegates human cultural achievements to a potential space arising from

primary object relationship (Winnicott 1971).

It follows logically that art - which bridges the distance between self

and object in a symbolic, simultaneously external and internal (mental),

space - must, by necessity, represent object relations. My paper endeavored

to prove this thesis with the added observation that in music (art) representation

of internal objects and the affects related to them, that is, internal

object relations, means an arrangement into cognitive structures. Therefore,

music (art) may be considered as a model of personality, the study of which

assumes a combined employ and integration of psychoanalytical and cognitive

psychological approaches.

NOTES

1Sacher and Geyer

were close friends. Before she died, Geyer gave him the letters (together

with the manuscript of the "First Violin Concerto" Bartók wrote

for her).

2Data in the literature

give the precise dates of the beginning and the end of the close relationship

between Bartók and Geyer: it lasted from June 28, 1907 to February

13, 1908 (Bónis, 1992; Tallián, 1981). During this period,

Bartók made the following collection trips: a brief trip to Transylvania

starting on July 1, 1907; he spent two months in Csík from July

6 and one week in Nyitra after November 1 (Bartók, Jr., 1981b).

3"Aunt Irma (Irma

Voit), Bartók's mother's sister who was older by eight years...

took care of their home after Bartók's father died and she lived

with her sister thereafter. Ever since she was a little girl, Bartók's

mother clung to Irma so much so that she often called her 'Stecknadel,'

meaning that she followed Irma around as if she were pinned to her skirt.

This intense mutual attachment made Mother and Aunt Irma seem virtually

as one person in the eyes of the family - one could not imagine one without

the other." (Márta Ziegler, Mrs Károly Ziegler, in: Bónis,

1995, 46).

4"I do not see

why you should condemn suicide as such a cowardly act! It's quite the contrary...

As long as my mother is alive, and as long as I have some interest in the

world, I will not commit suicide. But beyond that? Once I have no responsibility

towards any living person, once I live all by myself (never 'wavering'

even then) - why should suicide be a cowardly act? It's true, of course,

that it would not be a deed of great daring, but it could not be dismissed

as an act of cowardly indifference---" (September 11, 1907, cf. Bartók,

1971, 86.)

5"We may lay it

down that a happy person never phantasies, only an unsatisfied one. The

motive forces of phantasies are unsatisfied wishes, and every single phantasy

is the fulfillment of a wish, a correction of unsatisfying reality." (Freud,

S. 1908 [1907]. Creative writers and day-dreaming. S.E. 9:146.)

6On February 5,

1908.

7The separation

of the good and the bad aspects, their representation in two distinct movements

preserves the dichotomy; it's as if we were witnessing sublimation of the

splitting.

8The question

arises, what exactly does "internal object" mean in terms of clinical practice.

Are we dealing with a conceptual, pictorial, or some other representation

of an entity. And, in view of the fact - known from cognitive psychology

- that mental operation is tied to cognitive schemas, we may ask if representation

of internal objects in the cognitive structure is inevitable in each and

every case.

9"Kodály

said that the String Quartet No. I. was "inner drama, a sort of 'retour

ù la vie', the return to life a man who had reached the shores of

nothingness." The opening of this funeral hymn, a descending F minor seventh

chord, is the inversion of Stefi Geyer's leitmotif, a Freudian symbol,

a torch turned downward." (Tallián, 1988, 68)

REFERENCES

Bartók, Béla,

1979, Briefe an Stefi Geyer, Basel, Paul Sacher Stiftung (Private publication).

Bartók, Béla,

1971, Letters (Collected, Selected, Edited and Annotated by János

Demény, Transl. by Péter Balabán and István

Farkas), Budapest, Corvina Press.

Bartók, Béla,

Jr., 1981a, Bartók Béla családi levelei (Béla

Bartók's Family Correspondence), Budapest, Zenemûkiadó.

Bartók, Béla,

Jr., 1981b, Apám életének krónikája

(Chronicle of My Father's Life), Budapest, Zenemûkiadó.

Bónis, Ferenc, 1992,

Elsô hegedûverseny, elsô vonósnégyes: Bartók

zeneszerzôi pályájának fordulópontja

(First Violin Concerto, First String Quartet: The Turning Point in Bartók's

Career as a Composer), In: Hódolat Bartóknak és Kodálynak

(Homage to Bartók and Kodály), Budapest, Püski Kiadó

Ltd.

Böhm, László,

1990, Zenei Mûszótár (Dictionary of Music), Budapest,

Editio Musica.

Horgász, Csaba,

1993, Pilinszky Simon Áron címû

novellájának pszichoanalitikus megközelítése.

Kísérlet a tárgykapcsolati szemlélet mûértelmezésben

való alkalmazására (Psychoanalytical approach to János

Pilinszky's novel, Áron Simon. An attempt to apply the object relation

concept in the interpretation of works of art), Thalassa (4), 1, 92-106.

Horgász, Csaba,

1995, Bartók

Béla személyiségérôl és mûvészi

világképérôl (On Béla Bartók's

personality and artistic view of the world), Thalassa (6), 1-2, 36-59.

Kroó, György,

1974, Guide to Bartók (Transl. by Ruth Pataki and Mária Steiner),

Budapest, Corvina Press.

Lendvai, Ernõ,

1971, A dualitás elve. Két portré (The principle of

duality. Two Portraits), In: Bartók költõi világa

(Bartók's Poetic World), Budapest, Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó,

59-75. [English: Lendvai, Ernõ, 1971, Bartók's Poetic World,

Publishing House of Belles-lettres.]

Tallián, Tibor,

1988, Béla Bartók, The Man and His Work (Transl. by Gyula

Gulyás), Budapest: Corvina.

Winnicot, D.W., 1971,

Playing and Reality, London, Tavistock Publications.