ACCESS PROGRAM FINAL REPORT

IMAGE-AIDED GUIDANCE, NAVIGATION, & CONTROL

Guidance, Navigation, & Control Center

Code 571

AAAS - American Association for the Advancement of Science

ACCESS - Achieving Competence in Computing,

Engineering, & Space Sciences

Project mentor: John Croft

July 30, 1998

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND

THE

ICT ALGORITHM

THE

ICT TESTBED

SUMMARY

OF MY INVOLVEMENT

FUTURE

RECOMMENDATIONS

CONCLUSIONS

REFERENCES

TABLE OF FIGURES

Figure

1. Uncorrected and Post-Processed Corrected Image

Figure

2. Line-Scan Camera Footprints

Figure

3. The ICT Algorithm

Figure

4. Image Target and Camera Pointing System

Figure

5. ICT Testbed Feedback Control Loop

ABSTRACT

This report discusses my project on Image-Aided Guidance, Navigation,

and Control (IA/GN&C) at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in

Greenbelt, Maryland. My involvement in this project was made possible by

the Achieving Competence in Computing, Engineering, and Space Sciences

(ACCESS) program, which is sponsored by the American Association for the

Advancement of Science (AAAS). During the 10-week summer internship, I

adapted software to incorporate new hardware and variations of the Image

Correlation Tracking (ICT) algorithm into an ICT Testbed. The ICT Testbed

is part of the Guidance, Navigation & Control Center (GN&C), code

571. The testbed is an initial step in the development of IA/GN&C

systems for satellites.

INTRODUCTION

The overall objective of Image-Aided Guidance, Navigation, & Control

(IA/GN&C) technology at NASA is to reduce the cost and size of systems

that control the pointing direction, or attitude, and determine the

position of Earth-referenced satellites. The GN&C Center is currently

collaborating with industry, academic institutions, and government

partners to achieve this goal.

Attitude control is a very important aspect of spacecraft design, and

engineers must constantly balance hardware performance with cost. Besides

the actual scientific instruments, a satellite must contain expensive and

bulky hardware such as star trackers, sun sensors, or horizon sensors to

control its attitude. Although these devices are constantly becoming more

accurate and less expensive, they still significantly reduce a satellite's

efficiency.

An IA/GN&C system eliminates this extra hardware. It uses images

from the on-board scientific instruments to control attitude and determine

position. By implementing IA/GN&C, small micro-satellites could be

built and launched at a fraction of today's costs.

Image Correlation Tracking (ICT) algorithms are the power behind IA/GN&C.

These algorithms use two-dimensional images from an on-board scientific

instrument or secondary low-cost camera. Basically, the ICT algorithm

estimates the shift within the plane of an image with respect to a

previous image, or with respect to an onboard map. This shift will be used

in a feedback control loop to the satellite's reaction wheels to reduce

the shift in the image plane. This stabilizes the image and the satellite

as well. In the future, IA/GN&C systems powered by ICT algorithms

could drastically change satellite attitude control and position

determination.

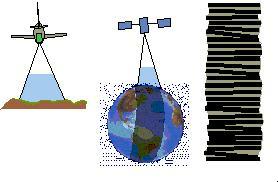

An airborne test environment is a logical step towards the goal of

satellite IA/GN&C. Low altitude remote sensing has been in use for

years and has many applications, especially in agriculture and forestry.

For example, remote sensing can spot a fast moving crop disease before it

spreads out of control. Many companies have recognized the demand for

aerial remote sensing technology and are developing improved techniques

for acquiring digital data.

Unfortunately, aerial remote sensing is still not very cost-effective.

As an airplane takes images, air turbulence shakes the plane (and camera),

which causes the image to become distorted. This distortion can only be

removed with expensive and time-consuming post-processing methods (Figure

1).

Figure 1. Uncorrected and Post-Processed

Corrected Image

(Figure courtesy of Peter Fricker, LH

Systems GimbH, Heerbrugg, Switzerland)

NASA hopes to use ICT algorithms to stabilize aerial

images. The ICT algorithm will be used in a feedback loop to control a

camera platform inside the airplane. By adjusting the angular displacement

of the camera platform, the image can be stabilized in real-time, reducing

the need for image post-processing. Additionally, aerial imaging projects

will prove very useful in the development of future satellite IA/GN&C

missions.

BACKGROUND

The objective of aerial imaging is to obtain high-resolution images of

large land areas, which is a very tedious process. For example, to get an

image with a resolution of 1x1 meter per pixel, images must be taken from

an altitude of about 1000 meters. At this relatively low height, each

frame taken by the aerial camera will capture very little land area. To

cover more area, aerial photographers use a technique called push-broom

imaging. Push-broom imaging involves making passes over a land area

and taking several images, or frames, on each pass. The frames are taken

at a rate such that there is some forward and side overlap of consecutive

images. This overlap is included to eliminate blank spaces caused by the

pitching, rolling, and yawing of the airplane as the images are being

simultaneously taken. After the plane lands, these frames are

painstakingly post-processed to "line up the edges" and create

one large, high-resolution image.

Analog aerial camera systems have been in widespread use for the past

seventy-five years. Analog cameras are inexpensive and produce excellent

images. In the computer age, however, digital images have proven to be

much more useful. Currently, most motion-corrected digital aerial images

are obtained by taking analog images, converting them to digital images,

then using costly and time consuming post-processing methods to remove

aircraft motion.

Two types of digital cameras are being tested to replace analog camera

systems. A digital framing camera takes pictures of aerial data and stores

it in a CCD array. The CCD array needs to be quite large to cover a

sufficient land area. It takes a long time for computers to store and

manipulate this large array, which makes real-time calculations very

inefficient.

A line-scan digital camera is arguably the more practical way to

directly record digital images. This camera works much like a desktop

scanner, which records data one line at a time. This method spreads out

the amount of information being processed, reduces the computational

burden, and makes real-time calculations much more feasible.

Aircraft motion still causes distortion in line-scan images, however, so

post-processing is still essential to obtain a clear image. The individual

lines taken by the camera do not match up, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1 shows an actual aerial image before and after post-processing.

Figure 2. Line-Scan Camera Footprints

Many applications still cannot use aerial data due to the expense and

time of post-processing. Frequently, aerial data users need to make

decisions based on recently acquired data. For example, precision-farming

techniques might use aerial imagery to determine which parts of a field

need extra irrigation water or fertilizer. Obviously, crop yields will not

be maximized if the aerial data is not quickly fed to the irrigation

control system.

Real-time image stabilization is a method to reduce, or perhaps even

eliminate post-processing. Currently, companies like 3DI in Easton,

Maryland, are experimenting with large gyro and GPS stabilized camera

platforms. Unfortunately, highly accurate inertial measurement units

(IMU's) are still very expensive and inconvenient.

NASA believes a less costly solution to this problem is the use of Image

Correlation Tracking algorithms. A separate, small, inexpensive camera

will be mounted on the platform next to the imaging camera. The ICT

algorithm will then use this camera to estimate the shift in the image

plane with respect to a previous image. This shift, combined with

information from the plane's altimeter and GPS unit, can be used to

control the camera platform and produce a stable image. Depending on the

application, minimal post-processing may still be required prior to

distribution.

THE ICT ALGORITHM

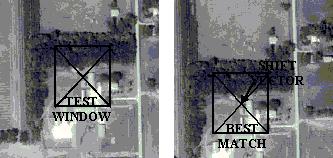

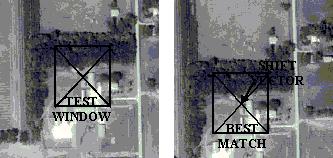

The ICT algorithm stabilizes images by estimating image shift.

Basically, it searches through an image to find a window that looks most

like a test window from a previous image (Figure 3). To find this

correlation, it performs a simple calculation on the image called a Mean

Square Difference (MSD) comparison.

Calculations can be performed on digital images because grayscale images

are made up of pixels. Each pixel's darkness is encoded by a value of 0 to

255. Thus, an image is actually just an array of integers ranging from 0

to 255. The MSD function squares the difference between a pixel in the

test window from the previous image and a pixel in the image in question.

It sums these squared differences across the whole test window area to

output a positive number, which describes the similarity between the two

windows. For example, if all the differences sum to zero, the MSD

comparison has found a window in the second image that is identical to the

test window in the previous image (Figure 3).

To visualize this process, imagine that the ICT algorithm shifts the

test window from the previous image inside the image in question, running

the MSD function at each point to find the lowest value. Once it finishes

searching the entire image, the smallest MSD value is chosen. A vector

from the center of the test window in the previous image to the center of

the window found by the MSD function is an estimate of the shift that

occurred from one frame to the next.

Figure 3 illustrates this process with actual aerial images. Due to

turbulence, the second image has shifted slightly down and to the left.

The ICT algorithm finds a window that is the best match for the test

window in the first image. This window is then used to estimate the shift

vector.

Figure 3. The ICT Algorithm

(images obtained from

http://www.terraserver.microsoft.com/)

Thus far, the shift in the image plane has been estimated to the nearest

pixel value. However, a better estimate of the shift would not need to be

at a finite pixel point. The best shift estimate could be somewhere in the

spaces between the pixels directly surrounding the finite pixel estimate.

To solve this, a curve is fitted to the surface of the pixels adjoining to

the finite pixel estimate. The minimum point on this fitted curve gives

sub-pixel accuracy to the original shift estimate.

THE ICT TESTBED

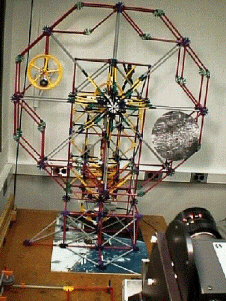

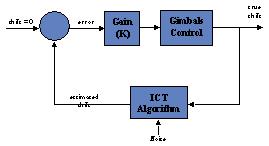

With sound theory in place, the GN&C center then developed a system

for testing the ICT algorithm on real images. A program running on

WindowsNT was created by John Downing to run the ICT algorithm and control

a two-axis gimbals system, which follows an image target around a wheel.

(Figure 4).

Figure 4. Image Target and

Camera Pointing System

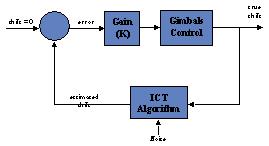

This ICT Testbed shown above uses a feedback control loop to command the

camera gimbals. As shown in Figure 5, the feedback is provided by the ICT

algorithm. Based on the error, the controller commands the camera platform

to move to a desired angular position. In addition, the gimbals system is

commanded to move at an angular velocity such that it reaches the desired

position within the loop's time interval. This velocity control provides a

very smooth transition between frames.

Figure 5. ICT Testbed

Feedback Control Loop

SUMMARY OF MY INVOLVEMENT

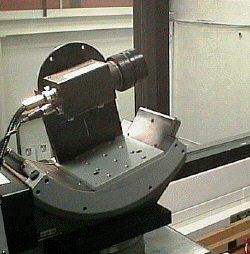

During my internship, I spent most of my time improving the ICT Testbed.

First, I implemented an improved camera pointing system. The new system

had better pointing accuracy and control over the gimbals. Using C++

programming language, I adapted the existing program code to include

commands to the new gimbals.

The next improvement I made to the feedback loop was angular velocity

control of the camera gimbals. The old camera pointing system lacked

velocity control and was simply commanded to move to a new position at a

rather high, constant velocity. This led to a very choppy transition

between consecutive frames.

No matter how small the angular position change, the gimbals moved there

at one constant speed. The camera then stopped and waited for the next

loop to execute. The target was still moving, however, which resulted in a

blurry image for the next loop execution. With the new system, the camera

is commanded to move at a controlled speed to the position so that it

arrives just as the camera captures the image for the next loop execution.

This results in clearer images and better results from the ICT Testbed,

since the camera is now moving at approximately the same speed as the

target.

The next option I installed in the program uses data from previous loop

executions to improve the performance of the ICT algorithm. This option

basically combines part of the previous shift estimate with part of the

current estimate to smooth out image motion through noisy areas. A

user-defined constant can be changed to determine exactly what portions of

the old and new data will be used in the estimate.

The final addition I made to the ICT program is an initial guess option.

Since the target moves in an approximate circle around the wheel, it is

possible to calculate an approximate shift in the image plane that will

occur during the next loop execution. Thus, the ICT algorithm now searches

only a small area around this logical guess to find a shift estimate,

which increases the robustness of the ICT algorithm. A larger test window

can be used over a smaller search area, which theoretically produces a

more accurate shift estimate.

FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS

The next step in IA/GN&C is to develop and demonstrate the

technology in an airborne environment. A new camera positioning system for

use in an aircraft should first be tested in a laboratory. A high quality

vision processing board is essential to this system to increase the

calculation speed of the ICT algorithm. Implementation of a Kalman filter

into the software will further improve results. Evaluation of airborne

tests can then be used to develop IA/GN&C on satellite missions.

CONCLUSIONS

Image-Aided Guidance, Navigation, & Control has the potential to

change both aerial imaging and satellite technologies. As computer

processing speed increases and digital storage capacity approaches

infinity, digital aerial images could become inexpensive and instantly

available to users. Results from aerial imaging research can be used to

develop IA/GN&C for satellite systems. After more research,

inexpensive micro-satellites using IA/GN&C systems could revolutionize

the aerospace industry.

REFERENCES

Bolton, J. (1998). Greenbelt, MD: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code

730, Systems Engineering Division.

Croft, J. (1998). Greenbelt, MD: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code

571, GN&C Systems Engineering Branch.

Downing, J. P., & Suber, J. L. (1998). ASTEC - Analysis and

simulation tools for engineering controls [computer software]. Greenbelt,

MD: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (v. 1.20).

Emami-Naeini, A., Franklin, G. F., & Powell, J. D. (1986, June).

Feedback control of dynamic systems. Reading, Massachusetts:

Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

Fricker, P. (1998, July 13). Digital airborne photogrammetric

cameras. Slide presentation at ISPRS Symposium, July 6-10, 1998.

Heerbrugg, Switzerland: LH Systems GimbH

Friedland, B. (1986). Control system design - an introduction to

state space methods. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Houghton, M. (1998, March 23). GTO technical information page - image

correlation tracking [On-line]. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Available: Internet:

http://gnctech.gsfc.nasa.gov/gto/tech/itc/airborne.html

Houghton, M. (1998, March 23). About GTO [On-line]. NASA Goddard

Space Flight Center Available: Internet:

http://gnctech.gsfc.nasa.gov/gto/about/index.html

Oshman, Y. (1998). Motion estimation via image registration. Paper

explaining image correlation tracking techniques. Greenbelt, MD: NASA

Goddard Space Flight Center.

![]()

![]()