In 1887, two physicists created an experiment to measure the Earth with

respect to the so-called "preferred" reference frame that Maxwell's equations

seemd to suggest.

Albert Michelson and Edward Morley's experiment was

asking whether the transit time would be equal for the two roundtrips of the

light beams in their experiment (See below for a description of the

experiment).

They measured this time for the light beams by recombining

the beams when they arrived back at their starting point. The light waves would

then be superimposed, one on top of the other. If the light beams had different

travel times, then their phases would be out of line when recombined. Light

waves with different phases produces a pattern of light and dark when viewed by

an inferometer (See below).

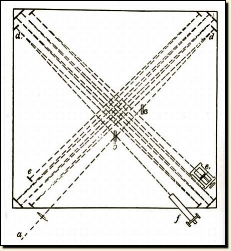

Interference "fringes" showing no

change as the interferometer is rotated. (G. Joos, Lehrbuch der Theoretischen

Physik, Akademische Verlags., Leipzig, 1930)

George Fitzgerald

was the first physicist to accept the idea of the experiement, he

wrote:

"I have read with much interest Messrs. Michelson and Morley's

wonderfully delicate experiment....Their result seems opposed to other

experiments....I would suggest that almost the only hypothesis that can

reconcile this opposition si that the length of material bodies changes,

according as they are moving through absolute space or across it, by an amount

depending on the square of the ratio of their velocities to that of

light."

But when the experiment was completed, they observed no

difference in the light travel times. They tried the experiment many more times

and at different times of the year, but eventually conceded that light's speed

is the same for any direction. Even with their experimental limitations

recognized, the speed of light had to be equal in both directions. This result

was important because it meant that Newtonian physics were valid -- there was

nothing wrong its foundations. Physicists could trust Newton's laws and not

worry about there being a preferred reference frame that might make their

measurements and calculations, and therefore theories, invalid.

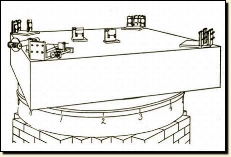

The Michelson-Morley Inferometer was an experimental

setup in which a beam splitter split a light beam into two parts. One half moved

in one direction, struck a mirror, and then was reflected back to another

mirror. The other half of the beam did the same thing, but in a different

direction.

The Michelson-Morley Inferometer was an experimental

setup in which a beam splitter split a light beam into two parts. One half moved

in one direction, struck a mirror, and then was reflected back to another

mirror. The other half of the beam did the same thing, but in a different

direction.

The setup they used could be rotated. Two different arms

(which the light beam halves traveled) could be moved in the direction the

Earth's motion. So the apparatus had a light source, a beam splitter, and

several angled mirrors to reflect the light back.

The original apparatus

was mounted on a block of stone that floated in a mercury pool. They could

rotate the block to see changes relating to the Earth's motion in orbiting the

sun. One set of light beams was set to travel parallel to the direction of the

Earth through space, while another set of light beams was set to travel cross

this motion.

James

Maxwell had a theory showing that electricity and magnetism were actually only

part of one electromagnetic force. He was then later able to show that

electromagnetic radiation was actually light itself. But his theory and

equations were dependant on the speed the light travels. But velocity is

relative, so his equations were not invariant -- they were relative.

James

Maxwell had a theory showing that electricity and magnetism were actually only

part of one electromagnetic force. He was then later able to show that

electromagnetic radiation was actually light itself. But his theory and

equations were dependant on the speed the light travels. But velocity is

relative, so his equations were not invariant -- they were relative.

Yet

the lack of invariance did not bother physicists of the time, at first that is.

The early reasoning was that light traveled through a medium, the luminiferous ether. They reasoned this because waves in matter

required a medium in which to propagate (move). But one should keep in mind that

this is not the same as Aristotle's ether. This luminiferous ether apparently

only existed to provide the expected medium for light; it had no mass and could

not be seen. It was wondered why the ether should exist for so special or

specific a function, becuase air does not exist solely for sound waves to move

through. But at the time, the view of waves was so set that no other alternative

was taken seriously.

Electromagnetic waves,

traveling disturbances in the electromagnetic spectrum,

do not need to move through anything to propagate (see previous Page). Because

electromagnetic waves share the same nature, they differ only by wavelength.

Groups of frequencies, or bands, divide the spectrum.

Radio waves occur at low frequencies, and then moving to the higher frequencies

are microwaves, infrared radiation, visible light, ultraviolet

radiation, X-rays, and at the very shortest frequency, gamma radiation. But the only reason these waves have different

names is because of their separate discoveries before it was known they were of

the same nature. The band division has so signifigance. Visible light, that

which we can all see, is not fundametally different from any of the other

waves.

The speed

of the motion of waves in a vacuum is the speed of light. All electromagnetic

waves move at this speed, but only in a vacuum. When moving through a medium of

some sort, a group of electromagnetic waves will travel through the medium at

different speeds. This is called dispersion.

All

the wavelengths in the visible band of the electromagnetic spectrum compose

white light. When white light passes through a prism, the different wavelengths

move at slightly different speeds through the glass and make them refract

differently at the two surfaces they cross. The prism splits the white light

into its "colored" components.

All

the wavelengths in the visible band of the electromagnetic spectrum compose

white light. When white light passes through a prism, the different wavelengths

move at slightly different speeds through the glass and make them refract

differently at the two surfaces they cross. The prism splits the white light

into its "colored" components.

But...

Under Galilean

transformations, however, Newton's laws of an object's motion are invariant (please see the link if you need a recap of

invariance and transformations). All frames are equal and there is no specific

rest frame. The transformations are supposed to link observations in one frame

to how the observations should look in another frame. Yet, with the

transformations, the equations associated with electromagnetism are not

invariant. The speed of light in electromagnetism is not an invariant quantity /

measurement.

Maxwell, the creator of the electromagnetism equations,

thought there should be a specific frame where his equations would be correct,

corresponding to the idea of the specific rest frame. If so, then all

measurements in any other frame would be related to the rest frame because an

observer would have to recognize the relative motion between the rest frame and

whatever other frame the measurement are being taken from.

But, again,

the Michelson-Morley experiment could not detect or find evidence for motion

with respect to a specific rest frame. In the absence of this frame, the speed

of light didn't have a special frame. Two possibilites that physicists didn't

want to consider arose:

- Maxwell's equations were wrong, or even maybe the physics of light wasn't

the same for all inertial frames.

or

- Galileo's transformations were not right. But this possiblity would

suggest something was wrong with Newton's mechanics.

But the

problem still existed that Newtonian equations were just as successful at

explaining mechanics as Maxwell's equations were at explaining electromagnetism.

Explaining the Result

In 1889,

George F.FitzGerald made one of the first attempts to explain the

Michelson-Morley result. His theory was that an object moving through a frame

would shrink in the direction of its motion because of the ether. If an arm on

the inferometer was shortened in the direction parallel to the Earth's motion,

the travel distance for the light moving that direction would be shortened by

the amount needed to make up the change in the speed of the light's propagation.

If this was done, the trip time for both light beams would be equal, and

not produce the pattern of light and dark fringes. But

there was no theory explaining why objects would contract this way. One

hypothesis was that because intermolecular forces are electromagnetic in nature,

then maybe matter's structure was affected by motion.

But a lot of

scientists clung to a conservative view, that moving objects drag the ether

along with them -- near the Earth's surface then, no relative motion and drag

would be detected. Part of this theory was due to the knowledge that light

moving through a moving fluid was different than if the fluid was at rest. Some

of the fluid's velocity taken up by light. But if light is dragging the ether,

it should lose energy and slow down in orbit, ultimately falling into the sun.

Yet no effect like this was observed.

Ernest Mach had a braver proposal

for the Michelson-Morley result. He said that no ether-relative motion was seen

because the ether didn't exist. Because the ether was not detected after an

elaborate experiment to test its existence, he said, then the theory was proved

wrong.

With Fitzgerald's theory, there was not any known force that

could make a moving object shrink along its direction of movement. Hendrick

Lorentz believed the result of the Michelson-Morley experiment, but at the same

time he took Fitzgerald's suggestion of contraction seriously. Fitzgerald, Henri

Poincare, and Joseph Lamour reexamined electromagnetism and found something

peculiar. If Maxwell's equations were expressed by electric and magnetic fields

measured at rest, the equations took on a simple, pleasing mathmeatical form.

However, if the equations were expressed in terms of different fields

experienced by someone moving through them (the ether), then the equations took

on a more complicated appearance. The laws or equations could be made to appear

simple by imagning that all moving objects shrink by the amount Fitzgerald's

theory suggested. This thought woulde plain the Michelson-Morley result. But

this wasn't enough, because to make the equations simple, it would also have to

be imagined that time moves more slowly as well.

This site maintained by Adam

Johnsen.

@1999