PART OF THE ARTSCHOOL

ONLINE NETWORK

PART OF THE ARTSCHOOL

ONLINE NETWORK

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF HENRI MATISSE

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF HENRI MATISSE

Henri Matisse was one of the most innovative artists

of this century, equaled only by Picasso. His dazzling experiments with

color marked a turning point in the history of art, and formed the basis

for most subsequent artistic developments. Matisse took to painting relatively

late in life, while recovering from a brief illness. He immediately found

in it both an ideal means of expression and a refuge from everyday existence.

After a short period as leader of the Fauvist movement, Matisse forged

his own unique style, combining the simplicity of Cezanne with a brilliantly

expressive use of color. His radiant compositions came increasingly to

reflect his own aspirations for a life free from trouble and nervous excitement.

In reality, his life was largely uneventful, particularly his last years,

spent peacefully in the South of France.

Henri Emile Benoit Matisse was born on 31 December 1869

in the northern French town of Le Cateau, at his maternal grandmother's.

Both his parents came from Le Cateau, but had met in Paris where his mother,

Anna, had worked as a milliner and Emile, his father, had been a draper's

assistant. Shortly after the birth, the family moved to the nearby village

of Bohain-en-Vermandois, where Emile set up shop as a druggist and grain

merchant. This commercial heritage was to prove useful as, throughout his

life, Matisse displayed a keen business acumen.

DISCOVERING ART

At first, Matisse gave little indication of his future brilliance

and individuality as an artist. At the age of ten, he attended the lycee

in the neighboring town of St Quentin, studying Latin and Greek, and in

1887, he was sent to Paris to study law. But it was not until he was nearly

19, that he began to take a serious interest in art. Working as a lawyer's

clerk in St Quentin, he attended early morning drawing classes at the Ecole

Quentin de la Tour, working assiduously from plaster casts between 6:30

and 7:30 am each day. But it was when he was convalescing from appendicitis

the following year that he took up painting, and it came as a revelation

to him. He recalled later, "When I started to paint, I felt transported

into a kind of paradise....In everyday life, I was usually bored and vexed

by the things that people were always telling me I must do. Starting to

paint, I felt gloriously free, quiet and alone."

With his father's permission, Matisse gave up law and

set off for Paris again - this time, to study with the fashionable and

most successful academic painter of his day, Adolphe Bouguereau. But Matisse

was soon to become disillusioned with Bouguereau's facile and repetitive

productions. In 1892, he became an unofficial student at the Ecole des

Beaux-Arts under the aegis of Gustave Moreau. Moreau was a liberal and

open-minded teacher, who encouraged his students to follow their own paths

and to paint right from the start of the course to develop their gifts

as colorists. He not only urged Matisse to copy Old Masters in the Louvre,

but also to go into the streets and draw, taking his subject-matter from

everyday life. Matisse made close friends in Moreau's studio, among them,

Albert Marquet, who joined Matisse in "creating" Fauvism some five years

later.

Life for Matisse in Paris of the belle epoque

was a struggle. By 1894, he already had a daughter, Marguerite, to support

(like much of Matisse's personal life, her origins can only be the subject

of conjecture). But gradually, Matisse's relatively unadventurous early

works, consisting largely of still-lifes and interiors in subdued colors,

began to win him success within the Parisian artistic establishment. Four

were exhibited at the 1896 Salon of the Societe Nationale des Beaux-Arts

and at the end of the exhibition, Matisse was elected an Associate Member

of the Societe. He looked set on the road to a successful, if unexciting,

professional artistic career.

However, Matisse was never one to bow to the dictates

of fashion, or the demands of the academic establishment. During the following

year, he presented to the Salon an ambitious still-life The Dinning

Table (orLa Desserte) in an Impressionistic style. Although

Impressionism was over twenty years old, it was still an anathema to the

establishment. The Societe were bitterly disappointed by Matisse's entry,

and after 1899, he did not exhibit with them.

The next ten years were years of poverty and hardship

for Matisse, lightened only by his marriage in January 1898 to Amelie Parayre,

whom he had met a few months before at a wedding. She was to prove a devoted

wife and mother - Jean was born in 1899, Pierre, in 1900 - and like Matisse's

mother, set herself up as a milliner to support her husband's talent; she

also modeled for him for several years. Her love of Oriental patterned

fabrics is depicted in her husband's portraits of her in a Japanese kimono.

For their honeymoon, they went to London, where Matisse studied the Turners,

as advised by Pisarro. On their return to France, they made an extended

trip to Corsica - Matisse's first experience of the Mediterranean light

and color, which were to play such an important part in his art.

On their return to Paris, the Matisses set up home in

an apartment on the Quai St Michel, near Matisse's friend, Marquet. Here,

Matisse devoted himself to painting and sculpture, and, to alleviate financial

difficulties, took a job with a theatrical scene-painter, meticulously

painting miles of laurel leaves to decorate the hall then under construction

for the 1900 Exposition Universelle.

The

first major turning point in Matisse's life came when he and his family

spent a summer holiday at St Tropez, near the villas of Paul Signac and

Henri-Edmond Cross, two major Neo-Impressionist painters. Under their influence,

Matisse began to paint in bright, vivid colors applied in a divisionist

technique, which was to culminate in Luxe, Calme et Volupte. (left)

The

first major turning point in Matisse's life came when he and his family

spent a summer holiday at St Tropez, near the villas of Paul Signac and

Henri-Edmond Cross, two major Neo-Impressionist painters. Under their influence,

Matisse began to paint in bright, vivid colors applied in a divisionist

technique, which was to culminate in Luxe, Calme et Volupte. (left)

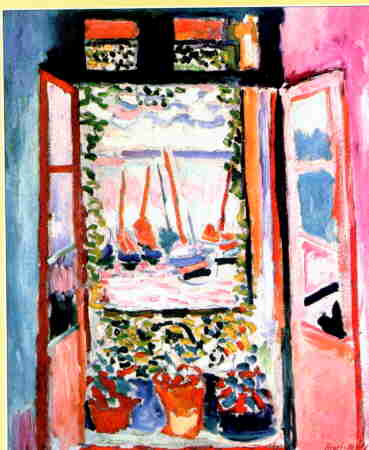

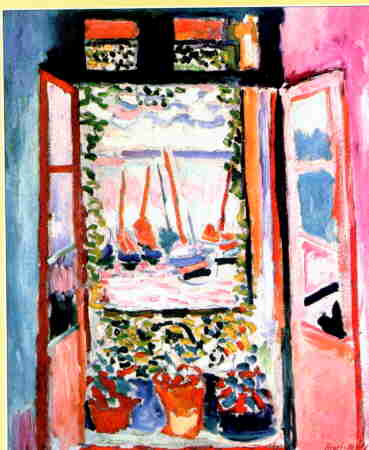

The following year, during a summer holiday at Collioure,

Matisse produced his first works in the Fauvist style. On his return to

Paris, he exhibited several of these paintings, including The Open Window

(below), and a portrait of Madame Matisse (look in Matisse Gallery, bottom

of page), at the notorious 1905 Salon d'Automne, along with works by Marquet,

Vlaminck and Derain.

The

paintings caused a furor. They were described as "pictorial aberrations"

and "unspeakable fantasies", and the painters themselves were labeled,

"fauves" or "wild beasts", because of the "savage" use of color.

The

paintings caused a furor. They were described as "pictorial aberrations"

and "unspeakable fantasies", and the painters themselves were labeled,

"fauves" or "wild beasts", because of the "savage" use of color.

The next major landmark in Matisse's life, was his introduction

to the Stein family. Leo, Michael and their more famous authoress sister,

Gertude, were among the most adventurous collectors of the day - and during

the next few years they bought many of Matisse's most controversial works.

The Steins also introduced him to a circle of enlightened critics, dealers

and connoisseurs. Matisse's fortunes improved dramatically - he had acquired

discerning patrons at last. He also acquired a regular contract with a

prestigious Parisian dealer and moved into a large house with grounds -

"our little Luxembourg" - in the suburbs of Issy-les-Moulineaux. He could

travel frequently and made trips to North Africa and Germany where he saw

the grand Islamic Exhibition in 1910.

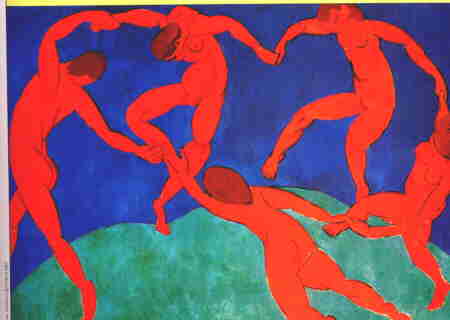

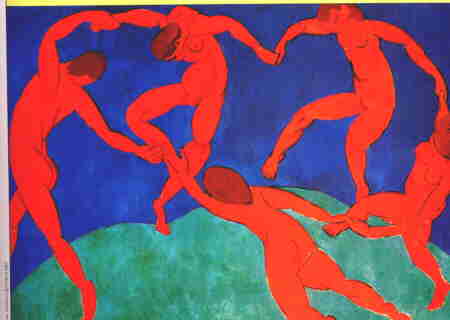

Matisse also attracted the patronage of a rich, cultivated

Russian merchant, Sergei Shchukin. Looking more like a Tatar nomad of the

Steppes, Shchukin was the ideal patron: not only incredibly wealthy, but

unprejudiced and with vision. In 1909, he commissioned two large mural

decorations for his baroque palace of a home in Moscow, including Dance.

(below)

Thus

the first decade of the new century was spent in the flush of prosperity,

with travels further afield to Russia, Morocco and Spain. However, in 1914

the war temporarily interrupted Matisse's travels. Too old to enlist, it

shattered his peace of mind, for he was continually anxious about the fate

of his friends. He painted little during the next two years and concentrated

instead on etching and devoted himself to the study of the violin. He would

joke in later life that it was insurance - if his eye sight failed him,

he could always busk.

MEDITERRANEAN SEDUCTION

From 1916, Matisse began to spend the winter months at Nice

on the Riviera. Apart from the availability of many attractive Mediterranean

models, the dazzling light - its play on the white stucco buildings and

clear sea - was irresistible to an artist for whom colors and light where

to become a preoccupation for the next ten years. For the rest of his life,

Matisse spent most of his winters in Nice - as if on sabbatical from domesticity

- moving from one hotel to another, painting, rowing and playing the violin.

Thus

the first decade of the new century was spent in the flush of prosperity,

with travels further afield to Russia, Morocco and Spain. However, in 1914

the war temporarily interrupted Matisse's travels. Too old to enlist, it

shattered his peace of mind, for he was continually anxious about the fate

of his friends. He painted little during the next two years and concentrated

instead on etching and devoted himself to the study of the violin. He would

joke in later life that it was insurance - if his eye sight failed him,

he could always busk.

MEDITERRANEAN SEDUCTION

From 1916, Matisse began to spend the winter months at Nice

on the Riviera. Apart from the availability of many attractive Mediterranean

models, the dazzling light - its play on the white stucco buildings and

clear sea - was irresistible to an artist for whom colors and light where

to become a preoccupation for the next ten years. For the rest of his life,

Matisse spent most of his winters in Nice - as if on sabbatical from domesticity

- moving from one hotel to another, painting, rowing and playing the violin.

The peace in Matisse's life during these years is reflected

in a series of quiet, contemplative interiors, such as the Woman and

Goldfish and in his languorous odalisques. These works were more acceptable

to the establishment than those of his Fauvist years and from 1921, Matisse

began to gain official recognition. That year, The French government purchased

one of his paintings, and examples of his work began to enter major public

collections all over the world. In 1925, he was created a Chevalier of

the Legion of Honour. For many years, Matisse had suffered from the backlash

of the Fauvist episode, which saw him branded as "loathsome", "abnormal"

and "degenerate". This characterization of Matisse was entirely at odds

with his true nature. He was not a passive or tranquil man and suffered

continual anxiety about his art. But in his outward behavior, he was quiet,

amiable and modest. Fernande Olivier, Picasso's mistress, described him

as a "sympathetic character"....of an astonishing lucidity of spirit, precise,

concise, intelligent". After a particularly naive response by an American

interviewer, Matisse is said to have pleaded, "Oh, do tell the American

people that I am a normal man....."

The 1930s were years of experiment. Matisse made a trip

to Tahiti via America in 1930. He denied that the trip was a flight from

Western civilization and was left strangely dissatisfied by the experience.

Also in 1930, Matisse undertook to provide the illustrations for a book

of poems by the Symbolist poet, Mallarme, and in 1931, he accepted the

commission to provide a large-scale mural decoration for the Barnes Foundation

in Philadelphia. Although the project posed monumental problems, Matisse

re-worked the entire design when he learned that he had been given incorrect

measurements. Exhausted, he retreated to Italy, and revisited Giotto's

murals.

In 1937, he designed the scenery and costumes for a production

of Shostakovich's Le Rouge et le Noir by the Ballets Russes of Monte

Carlo, and the following year, he began working extensively in cut paper

or gouache decoupee, a project which culminated in the publication

of jazz.

A SECOND LIFE

By 1939, Matisse was becoming increasingly anxious about

the uncertain climate as war was about to break out. His separation from

his wife, though never legalized, was pretty much on the cards. (She and

Marguerite went on to work for the French Resistance and were captured

by the Gestapo, though later rescued.) Matisse was seriously ill with duodenal

cancer and had two major operations in 1941: surprised to find he had survived

them, he felt he had been granted another life. By now, he was looked after

by Lydia Delektorskaya, the young Russian model he had painted in the 1930s,

who had become his muse, confidante and companion. Matisse had acquired

a suite in the palatial Hotel Regina ai Nice, where he returned to convalesce

- but continued working, even from his bed: he fixed charcoal onto long

poles and drew on the walls and ceiling.

As the Italians advanced on Nice, Matisse moved to the

nearby hill town of Vence. It was here that he was persuaded by one of

his ex-models, now a nun, to undertake the most important project of his

last years - the decoration of the Chapel of the Rosary. By the time the

chapel was consecrated in 1951, Matisse was too frail to attend the ceremony.

Three years later, he died peacefully at Nice, on 3 November 1954, aged

84.

MATISSE GALLERY

BACK TO START PAGE

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF HENRI MATISSE

THE

LIFE AND TIMES OF HENRI MATISSE

The

first major turning point in Matisse's life came when he and his family

spent a summer holiday at St Tropez, near the villas of Paul Signac and

Henri-Edmond Cross, two major Neo-Impressionist painters. Under their influence,

Matisse began to paint in bright, vivid colors applied in a divisionist

technique, which was to culminate in Luxe, Calme et Volupte. (left)

The

first major turning point in Matisse's life came when he and his family

spent a summer holiday at St Tropez, near the villas of Paul Signac and

Henri-Edmond Cross, two major Neo-Impressionist painters. Under their influence,

Matisse began to paint in bright, vivid colors applied in a divisionist

technique, which was to culminate in Luxe, Calme et Volupte. (left)

The

paintings caused a furor. They were described as "pictorial aberrations"

and "unspeakable fantasies", and the painters themselves were labeled,

"fauves" or "wild beasts", because of the "savage" use of color.

The

paintings caused a furor. They were described as "pictorial aberrations"

and "unspeakable fantasies", and the painters themselves were labeled,

"fauves" or "wild beasts", because of the "savage" use of color.

Thus

the first decade of the new century was spent in the flush of prosperity,

with travels further afield to Russia, Morocco and Spain. However, in 1914

the war temporarily interrupted Matisse's travels. Too old to enlist, it

shattered his peace of mind, for he was continually anxious about the fate

of his friends. He painted little during the next two years and concentrated

instead on etching and devoted himself to the study of the violin. He would

joke in later life that it was insurance - if his eye sight failed him,

he could always busk.

Thus

the first decade of the new century was spent in the flush of prosperity,

with travels further afield to Russia, Morocco and Spain. However, in 1914

the war temporarily interrupted Matisse's travels. Too old to enlist, it

shattered his peace of mind, for he was continually anxious about the fate

of his friends. He painted little during the next two years and concentrated

instead on etching and devoted himself to the study of the violin. He would

joke in later life that it was insurance - if his eye sight failed him,

he could always busk.