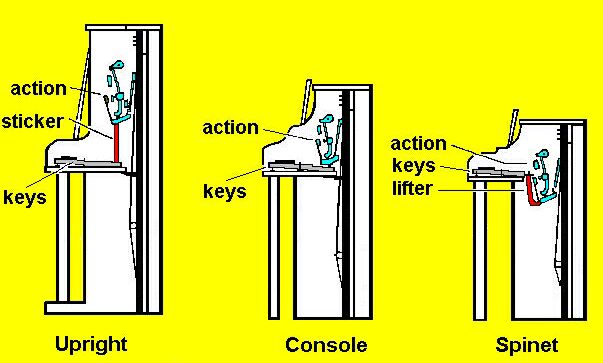

There are two types of modern acoustic pianos, VERTICALS and GRANDS. Of the vertical pianos, there are four basic styles; the Upright, Console, Studio and Spinet. Since piano makers frequently vary the size of their cabinet work in different models it's often difficult to distinguish between a console and a spinet, or a studio and an upright, simply by looking at the case. Technically, the classification of these styles is determined by the placement of the action (i.e., the collection of parts that strike the strings) in relation to the keyboard, as shown in the drawing below.

On full Uprights the action is ABOVE the keyboard and connected to the keys by a wooden rod called a "sticker." On Consoles the action is compressed slightly to save room and rides directly ON the keys (or rather, on a small brass screw connected to the keys, called a "capstan"). On Spinets the action is dropped BELOW the keyboard to save space and is connected to the keys by a wire or wooden rod called a "lifter." The spinet action is usually referred to as a "drop action." Studio model pianos are usually constructed like a console, except they are a bit taller and use a full sized upright action.

In theory, the console action (referred to as a "direct blow" action) would seem to be superior to the other two due to its simpler construction. In fact, however, there is little difference between the upright and console in terms of keyboard response...and certainly not enough to make up for the upright's superior tonal qualities, which can be attributed to its longer strings and larger soundboard. Studio pianos are something of a compromise, being the piano manufacturer's attempt to build an instrument with a direct console action and still retain some of the tonal qualities of the big uprights.

The spinet drop action, on the other hand, is just a bad idea all the way around. It adds a troublesome and noisy "lifter," which makes it difficult to remove the action (and hence makes servicing more expensive). Also, to place the action below the keyboard, the keys have been shortened, seriously compromising key balance and making the spinet action loose and sloppy. In addition, the spinet's shorter, heavier wound bass strings and small soundboard make for a less resonant bass tone. The irony of the spinet design is that it was intended to save space, yet in fact, is the same width and depth as the console or upright and uses just as much floor space. The only space saved is between the top of the piano and the ceiling. Hmmmm! Nonetheless, spinets remain popular and their resale value is high, though at the moment they are no longer being built. Most are perfectly adequate for amateur players, despite their shortcomings, however. Perhaps the best spinet was the Acrosonic, produced by the Baldwin Piano Company.

Grand pianos are wing shaped and are ALWAYS horizontal in construction, as in this drawing, hence there is no such thing as an "Upright Grand," though many Victorian piano makers labelled their instruments with that misnomer as a sales gimmick to cash in on the grand piano's prestige. Grands come in several sizes including the "baby" grand, which is usually around 5'6" from the keyboard to the back of the case. "Parlor" grand was a name given to instruments 6 or 7 feet in length, and of course a "concert" grand, the top of the line, is 9 feet in length. The extra string length and soundboard size of these big grands, along with their handmade construction, gives them a tonal quality and volume unmatched by any of the smaller models (it also gives them an unmatched price tag...some, such as Bosendorfer, sell for over $150,000...your little spinet is looking a bit better, huh?). As a matter of fact, grand pianos are always superior to all verticals, due to a better design and a quicker key response, and are the choice of most serious performers who can afford them.

An old style of piano once very popular is the Square Grand. These things look like a large coffin with legs, and you will often see them in old movies and some museums. They were last produced by Steinway in 1896, though they were obsolete 40 years earlier. The construction of these old pianos was eccentric, to say the least, with a keyboard that had very long bass keys and very short treble keys, making playing them a real adventure. Tuning them was more like a nightmare. If you happen to stumble onto one of these antiques, resist the urge to buy it unless you're needing something to bury your uncle in (in which case be sure to hire plenty of pallbearers as these old monsters weight a ton). They were a mess even when new, due to the poor design, and are all virtually unplayable nowadays. As parts are no longer made, they are also not re-buildable, except by antique instrument collectors and masochists.

though they were obsolete 40 years earlier. The construction of these old pianos was eccentric, to say the least, with a keyboard that had very long bass keys and very short treble keys, making playing them a real adventure. Tuning them was more like a nightmare. If you happen to stumble onto one of these antiques, resist the urge to buy it unless you're needing something to bury your uncle in (in which case be sure to hire plenty of pallbearers as these old monsters weight a ton). They were a mess even when new, due to the poor design, and are all virtually unplayable nowadays. As parts are no longer made, they are also not re-buildable, except by antique instrument collectors and masochists.

Another odd-ball piano style that can sometimes be found in antique stores is the old European "cottage" piano. These pianos were small uprights, usually with fancy carvings on the case and often with elaborate candle holders on the front. They can be easily recognized if you remove the front of the case and view the action. Due to an obsolete arrangement of the dampers in front of the hammers rather than behind them, the mass of damper wires gives the action the appearance of a "birdcage," hence they were known to technicians by that nickname. Despite their obsolete design these pianos were still manufactured into the 20th century and imported to America by some British makers still upset over the Revolution. As with the square grand you should resist the urge to buy one unless you simply want it as furniture. They are difficult if not impossible to tune and nearly always impossible to repair as parts are no longer manufactured.

Another oddity of some European pianos, incidentally, is a shortened keyboard; i.e., 85 keys rather than the usual 88. This key arrangement does not necessarily date the piano as some makers have continued to produce them. Frankly, the last three treble keys were only added to piano keyboards in the late 19th century at the request of some flashy concert pianists. Most players can get by perfectly well without them, except in some very advanced 20th century concert compositions. Beethoven, Mozart and most other "classical" composers got along with keyboards that were an octave or more shorter than the modern 88 standard. In fact, the strings on these last three notes notes are so short, and the hammer striking point so precise, that they often sound more like a metallic thud than a musical tone, except on the very best of the big grands.