|

|

|

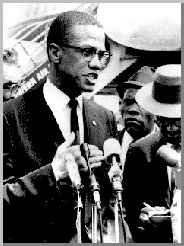

Malcolm X (May 19, 1925 - Feb.21, 1965) was an

influential American advocate of Black Nationalism

(see also slavery later in this section) and, as

a pioneer in articulating a vigorous self-defense against white violence,

a precursor of the black power movement of the late 1960s.

Malcolm X (May 19, 1925 - Feb.21, 1965) was an

influential American advocate of Black Nationalism

(see also slavery later in this section) and, as

a pioneer in articulating a vigorous self-defense against white violence,

a precursor of the black power movement of the late 1960s.

He became a rebellious youth after the death (1931) of his father, who the

family believed was murdered for advocating the ideas of Marcus Garvey.

Malcolm spent a few years in a foster home but became an excellent student

and was voted class president. At the age of 16, he moved east with relatives

and drifted to New York City, where he became involved in Harlem's underworld

of drugs, prostitution, and confidence games.

In prison for burglary from 1946 to 1952, he read widely and was converted to the teachings of Elijah Muhammad. On his release, he embraced the Black Muslims movement and changed his name to Malcolm X. Following his initial training, Malcolm became the leading spokesman for the Black Muslims to the outside world.

An ideological split between Malcolm and the more conservative Elijah Muhammad, and in 1963 Malcolm was suspended as a minister of the Black Muslims. After a pilgrimage to Mecca, he announced (1964) that he had become an orthodox Muslim and founded the rival Organization for Afro-American Unity. His travel in the Middle East and Africa gave him a more optimistic view regarding potential brotherhood between black and white Americans; he no longer preached racial separation, but rather a socialist revolution.

His career ended abruptly when he was shot and killed in New York City on Feb. 21, 1965, by assassins thought to be connected with the Black Muslims.

The autobiography of Malcolm X (dictated to Alex Haley, 1965) publicized Malcolm's ideas and became something of a classic in contemporary American literature. Published in 1965 shortly after Malcolm X's assassination, it is perhaps the most compelling work to come out of the civil rights movement of the 1960s in the United States. It is Malcolm X's account, as recorded by Alex Haley, of his life from his impoverished youth in a northern black ghetto through numerous imprisonments to his emergence as a power in the Black Muslims and his breach with that organization. Although he lashes out against whites and their power structure, Malcolm X does hold out the slim hope of reconciliation between the races in a new society based on social justice.

| Black Nationalism |

Malcom X Slavery

|

Organized black nationalist movements appear to have begun with Paul Cuffe

(1759-1817), a black sea captain. Between 1811 and 1815 he made the

first attempt to establish a black American colony in Africa, transporting

several dozen people to Africa.

Early in the 20th century W.E.B. Du Bois developed a sophisticated

rationale for a Pan-African movement that would join blacks in America and

Africa.

But not until after 1910 did a mass movement emerge with black nationalism

as its central theme. The leader of this new movement, Marcus Garvey,

recruited thousands into his Universal Negro Improvement Association

(UNIA). Its goals included a black nation oriented toward Africa but

controlled by black Americans. The UNIA developed the first major black

capitalist enterprises, including restaurants, grocery stores, hotels, and

a steamship line. Because of antagonism from whites and mismanagement at

the top, this movement failed, but it was soon followed by a number of

Africa-oriented movements, the most important of which was the

Nation of Islam, known inaccurately as the Black Muslims.

Beginning in the 1930s under the leadership of Elijah Muhammad, the

Nation of Islam grew to a membership of about 100,000 in the 1960s. Along

with Islamic and Christian ideas it emphasized black pride, the central

role of the male in the family, the importance of economic self-sufficiency,

and a way of life that has often been equated with middle-class morality.

It exchanged the goal of a separate nation outside the United States for

one of independence and autonomy within the United States. Perhaps its

best-known leader was Malcolm X.

By the late 1960s many themes of black nationalism became part of the

life-style of ordinary black Americans, particularly young people.

These ideas persist today in colleges and universities, many of which

have developed courses in black studies.

| Slavery |

Malcom X Black Nationalism

|

Slavery has appeared almost universally throughout history among peoples of every level of material culture, from ancient Greece or the United States in the 19th century to various African and American Indian societies.

Slavery is not unique to any particular type of economy. It existed among nomadic pastoralists of Asia, hunting societies of North American Indians, and sea people such as the Norsemen, as well as in settled agricultural groups, although the slaves traditionally served differing functions in these societies. Among agriculturists, slaves were valued primarily as the major work force in production. Such societies are sometimes referred to as commercial slave societies, exemplified by the Roman Empire and the Old South of the United States, distinguishing them from slave-owning societies, in which slaves were used principally for personal and domestic service, including concubinage.

The latter type of slavery traditionally existed in parts of the Middle East, Africa, and China. The more sophisticated agricultural societies, however, were able to use slaves most effectively, and in such societies slavery became systematic and highly institutionalized.

Although slaves would seem to be a primitive source of energy that would lose importance with the advance of mechanization, the opposite proved true in the United States; the cotton gin, which came into use after 1800, prepared cotton for marketing so rapidly that the demand for slaves increased rather than decreased.

Although the United States had put an end to slavery as that institution is here defined, a form of it persisted in tenant farming, debt peonage, and migrant labor, in the sense of work contracts that yield the worker little or no profit from labor or leave the worker perpetually in debt to the employer. In North America, blacks, Hispanics, and Mexicans suffer the most from such systems. Elsewhere in the world, notably in parts of Africa, Asia, and South America, these and more literal forms of slavery persist.

The Anti-Slavery Society for the Protection of Human Rights in London

estimates that debt bondage (in which impoverished, illiterate people work

for very low wages, borrow money from their employers, and pledge their

labor as security), serfdom that is called contract labor, sham adoptions,

servile forms of marriage, and other forms of servitude still oppress more

than 200 million poor people in the developing world. In the late 1980s the

society concentrated its efforts to improve the lot of such people in South

and Southeast Asia because of the magnitude of child-labor servitude there.

The society estimated that 50 million children in India alone were being

exploited.

The sale of children into bondage and the self-sale of impoverished persons

also continue in Asia. In some Asian nations there are young people of both

sexes living in enforced prostitution; they are kept illiterate and deprived

of all personal rights.

Saudi Arabia and Angola abolished slavery officially only in the 1960s. In Angola subsequently, however, contract workers in mines and on plantations, highways, and railroads seemed to be involuntarily conscripted and paid the equivalent of only a few cents a day. Observers confirm reports of unacknowledged slavery in other African countries.

The 20th century has nevertheless made some forward strides toward human

freedom through international organizations. The League of Nations, formed

following World War I, set up machinery for international cooperation toward

putting an end to slavery everywhere. The League's successor, the

United Nations ![]() ,

has continued and expanded the work of the League.

Its Declaration of Human Rights specifically

prohibits slavery and the slave trade, and the Security Council has

condemned forced labor.

,

has continued and expanded the work of the League.

Its Declaration of Human Rights specifically

prohibits slavery and the slave trade, and the Security Council has

condemned forced labor.

Perhaps more important than any declaration or agreement opposing slavery is

the work of the United Nations Economic and Social Council, the Food and

Agriculture Organization, the Educational, Scientific, and Cultural

Organization, and the World Health Organization. These international

bodies attack the conditions of hunger, weakness, and ignorance that

perpetuate the institution of slavery.

Go to the top of the page