|

|

|

Printing, in its broadest sense, is any process whereby one or more

identical copies are produced from a master image. It has ancients

origins.

Printing, in its broadest sense, is any process whereby one or more

identical copies are produced from a master image. It has ancients

origins.The master image can range from an inscription engraved in stone to an illustration cut into a wood block or a text stored as digital information in a computer. Image transfer, from master to copy, is usually accomplished with ink, and the transferring agent is most often the printing press. The development of new technologies has blurred traditional definitions of printing, however office copiers, for example, reproduce master images using electrostatically charged graphite toner.

The routine, though rudimentary, reproduction of textual matter first occurred near the beginning of the 8th century AD, when the Chinese began to experiment with the printing of relief, or raised, images cut in wood blocks. During the 11th century both the Koreans and the Chinese experimented with the manufacture of movable type made from clay and wood and, later, from bronze and iron. Although the notion of movable type was a major advance in printing technology, the complex characters that formed the written languages were too difficult to produce as individual pieces of type.

The German Johann Gutenberg, working 400 years later, enjoyed the advantage of a simple alphabet, and he worked out a method of casting type and printing so successful that its fundamental principles were not improved until well into the 19th century. Gutenberg's first book, a Latin Bible, was completed about the year 1455.

Later improvements to Gutenberg's screw press were largely devoted to increasing impression power, improving the clarity of the printed image, and devising a return mechanism for the press handle. Although 19th-century designers continued to improve the efficiency of the iron handpress, its practical limits were soon reached. Until recently, though, small-job printers continued to use the platen press, invented in the early 19th century. In 1811, Friedrich Koenig patented the first flatbed cylinder press, using a revolving cylinder instead of a flat platen to press sheets of paper against a flatbed of type.

The difficulty of making curved relief printing plates slowed the acceptance of the rotary press. By the 1870s, however, curved stereotype plates could be accurately cast, and they replaced Hoe's metal type. From that point until well into the 20th century, the press of choice - especially for newspaper publishers - became the automatic rotary cylinder press, printing both sides of a continuous web of paper. Steam provided power for the early machine presses; electric power was used from the end of the 19th century.

Books, ranging from ancient scrolls to today's mass-produced volumes, are an important storehouse of human knowledge. They originated in humanity's efforts to make permanent what oral tradition could not adequately preserve.

| History |

Printing Gutenberg Wood Block

|

The Book of the Dead, which is often considered the first book despite the existence of earlier papyrus fragments, contained prayers and magic formulas to guide the dead in the afterlife.

Protected between pairs of wooden boards and sewn together, bound volumes of vellum were the antecedents of books as they are known today, although the Chinese had at the time made books consisting of bamboo strips bound together with cord. Smooth, tough, and durable, vellum, for which the Latin name is still pergamena (parchment), forms an ideal writing material, although, in modern times, the high cost has limited its use to special purposes.

Bookbinding in the West originated with the gradual development of the codex - folded leaves or pages contained within two or more wooden tablets covered with a wax writing surface and held together by rings. By the 4th century these codices had largely replaced the scroll. The codex marked a revolutionary change from the rolled manuscript. Despite the cost of materials, great bibles and service books were produced, illuminated with pictures, decorated initials, and borders. Examples are the Book of Kells (8th century) and the Winchester Bible (pre-13th century).

Even so, few people could read during the Middle Ages, and virtually all

the manuscripts, knowledge, and literature of the ancient world, as well as

the Bible and the great texts of Christendom, were produced and preserved in

monasteries. A remarkable number of copies of works, both secular and

religious, were produced by hand copying.

By the 13th century the thrust of intellectual life had passed to the

universities. Workshops developed, and professional scribes became the

principal creators of books. More people could read, and many more books

were privately owned. Kings and rich laymen became patrons to the artists.

Medieval manuscripts were at first written in Romanesque script and later

in Gothic.

By the 14th century, in Italy, the humanists were turning for inspiration to the ancient world and were developing a new handwriting. Their capital letters were taken from Roman lapidary inscriptions and their lower case from the minuscule (small letter) manuscripts of the school of Charlemagne. When early printers produced the classics, they cut types derived from these scripts, from which the roman type commonly used today is a direct descendant. By the 15th century even more people could read, creating an urgent need for a less laborious method of book production - a need accentuated by the Renaissance and the Reformation.

The key to the invention of printing lay in movable type. This type might be set up in any order and mistakes corrected; after printing, the same type could be used again. Although similar printing had developed earlier in China and Korea, Louis Daguerre in 1839 had an enormous impact on all forms of pictorial reproduction and ultimately on the typesetting process itself. Among the processes made possible by photography were line engraving, rotogravure, and offset printing. The offset process remains an integral part of modern computerized printing. Despite technical advances, standards of design in book production had drastically declined by the middle of the 19th century.

Although the quality of paper used in mass production remains a problem, new, acid-free papers are now available, and many publishers have agreed to use them. (Most books published over the past century have been printed on paper with an acid content that turns pages yellow and brittle). Mass production, computerized printing techniques, the development of relatively inexpensive paperback editions, book clubs, and public libraries, among other factors, have made more books available to more people than ever before.

In this age of mechanization, book collecting is still prevalent. Collectors range from professional booksellers to bibliophiles who collect books for their literary value, their aesthetic appeal, or their monetary worth as an investment. For whatever reason - and despite the competition from television, movies, and other forms of entertainment - old books are still cherished and new books are still produced, bought, and read.

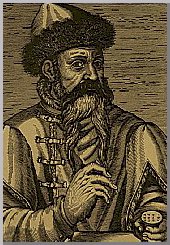

| Johann Gutenberg |

Printing History Wood Block

|

Johann Gutenberg (1398-1468) was a German goldsmith who is credited with

the invention and development in Europe of printing from movable type. His

invention fulfilled the needs of the age for more and cheaper reading

matter and foreshadowed the modern printing industry.

Johann Gutenberg (1398-1468) was a German goldsmith who is credited with

the invention and development in Europe of printing from movable type. His

invention fulfilled the needs of the age for more and cheaper reading

matter and foreshadowed the modern printing industry.Gutenberg first experimented with printing about 1440 in Strasbourg. By 1450 his invention had been perfected to a point where it could be exploited commercially. To produce the large numbers of individual pieces of type that were needed for the composition of a book, Gutenberg introduced the principle of replica-casting. Single letters were engraved in relief and then punched into slabs of brass to produce matrices from which replicas could be cast in molten metal. These were then combined to produce a flat printing surface, thus establishing the process of letterpress printing. The type was a rich decorative texture modeled on the Gothic handwriting of the period.

Gutenberg's second achievement lay in the development of an ink that would adhere to his metal type and that needed to be completely different in chemical composition from existing wood block printing inks. Gutenberg also transformed the winepress of the time into a screw-and-lever press capable of printing pages of type.

Gutenberg apparently abandoned printing altogether after 1465, possibly

because of blindness. He died on Feb. 3, 1468, in comparative poverty.

Only one major work can confidently be attributed to Gutenberg's own

workshop.

This is the Gutenberg Bible, the first book ever produced

mechanically, printed in Europe about 1455. The actual printing is

usually attributed to Gutenberg, but some scholars suggest that it may

have been done by his partner, Johann Fust, and Fust's son-in-law, Peter

Schoffer.

The 42-line Bible, of which fewer than 50 copies are extant, comprised

1,284 pages, each with 2 columns of text containing 42 lines to a column.

Each page held about 2,500 individual pieces of lead type, set by hand. The

German Gothic type-style was modeled on manuscripts of the period. Six presses

worked on the Bible simultaneously, printing 20 to 40 pages of type a day.

The Psalter, generally regarded as Europe's second printed book, is

sometimes attributed to Gutenberg because it includes his innovation of

polychrome initial letters using multiple inking on a single metal block.

The 36-line Bible (1458-59), of which 8 copies remain, and the Catholicon

(1460), are sometimes also attributed to Gutenberg.

| Wood Blocks |

Printing History Gutenberg

|

Blocks may have been used to print textiles in India as early as 400 BC.

Books were block printed in China in about the 9th century AD, as was the

paper money in Kublai Khan's 13th-century Mongol empire. The earliest

example of block-printed cloth from Egypt dates back to the 9th century,

but the technique was probably practiced there much earlier.

Block printing in Europe seems to have started in Italy in the 13th

century. During the 14th century the technique was used for illuminating

manuscripts in Germany, which became a major center for block-printed

textiles a century later. Some books were also block printed at this time,

but the invention of movable type by Gutenberg about 1450 ended

the use of blocks for all but the printing of textiles.

During the last half of the 18th century sizable block-printing industries were established in Europe. The first commercial block-printing enterprise in the New World was established in Philadelphia in 1772, and the technique remained important until well into the 20th century. Block printing today is fairly rare, having been almost entirely replaced by silk-screen printing.

Go to the top of the page